|

Portraits of Local Abolitionists and Reformers

The Rescue

of Harriet Powell

The Fugitive Slave Law and Its Impact

The Jerry Rescue and Its Aftermath

How the Antislavery Movement Used the Print Media

Maps and Charts

Related Links:

CNY Reads Miriam Grace

Monfredo's North Star Conspiracy

Borders: The 2005

Syracuse Symposium

SCRC Home

|

The Jerry Rescue and Its Aftermath

On the first of October 1851, William “Jerry” Henry, an escaped

slave and cooper residing in Syracuse, was arrested ostensibly for theft.

Only after he had been placed in manacles, however, was it revealed that

he had been arrested by federal marshals under the terms of the Fugitive

Slave Law passed in September of 1850. Jerry at that point struggled furiously

but was brought before the U.S. commissioner Joseph Sabine. A first attempt

to free him by abolitionists occurred in that office, and he was able

to escape from the building and flee to one of the bridges over the Erie

Canal, where he was recaptured and then delivered to the Police Justice

offices. It was in this location that the famous Jerry Rescue was effected

when a crowd of approximately twenty-five hundred people surrounded and

ultimately stormed the facility. A few shots from a pistol were fired,

but the sheer force of the crowd was sufficient to daunt the federal officers.

Jerry was successfully hidden in the city until he was transported to

freedom in Kingston, Ontario, where he remained until his death just a

few years later. The Jerry Rescue was celebrated as one of the great triumphs

of the antislavery movement and became an integral part of the lore and

the strategizing of abolitionists in the region.

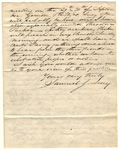

Letter of J. M. Clappe to Gerrit Smith, 3 January 1852. According to

court testimony subsequent to the Jerry Rescue, it appears that Clappe

was the first person to enter the Police Justice offices on the night

of the Jerry Rescue. Clappe was a “furnaceman” or ironworker

and may have been chosen as one of the first to breach the premises because

of his brawn. There could be no question as to his commitment to the antislavery

movement, however, because he was obliged, after conferring with the Boston

abolitionists Wendell Phillips, Amasa Soule (Sewel), and Francis Jackson,

to go into exile in St. Catharines, Ontario, to which he fled after the

rescue. Even though he inquires about returning to Syracuse at the close

of this letter, the city directories do not provide evidence of his return

until 1857:

I shal feele myself highly honord to recieve your kind and benevilent

counsil under my trying circumstances driven as I was from hoalm [home]

unexpectedley without an hours preperation....the caus of my leaving

so sudenly was the advise of my esteemed friend Mr C. A. Wheaton on

the night of the 3d of Oct following the memoriable first of Oct 1851

which as in all probibility you well know the part that I am charged

with[.] I hav for a long time ben sorry that I ever left Syracuse after

obtaining so glorious a victory as was don on that night[.] When I left

I started for pensylvania thinking of making my parents a visit but

thinking it not advisable I turned my course to NY Citty...and deeming

it not exactley the place for me under the advise of...friends I left

for Mass wheire I took counsil from Mr W Phillips[,] Sewel[,] Jackson

and others in Boston in regard to the propriety of going to canida...So

I went up into newhampshier and worked a few weeks then left for canida

by the way of the vermont central road to Ogdensburgh...I hav traveled

a long journey and now what I want to know is whether under presant

circumstances I had better remain here or return to Syracuse and run

the risk of conciquences[.] I do not wish to return without consulting

those that feele themselvs pledged to sustain each other in the caus

of rescuing the fujativ[.]

I hope you will excuse my roundabout way of puting the question and

my imperfections in the english language[.]

Speech of Rev. Samuel J. May, to the Convention of Citizens, of Onondaga

County (Syracuse: Agan and Summers, 1851). In this speech delivered just

two weeks after the Jerry Rescue, the Reverend Samuel May captured the

sentiment of the crowd in stirring terms:

But when the people saw a man dragged through the streets, chained

and held down in a cart by four or six others who were upon him; treated

as if he were the worst of felons; and learnt that it was only because

he had assumed to be what God made him to be, a man, and not a slave—when

this came to be known throughout the streets, there was a mighty throbbing

of the public heart; an all but unanimous up rising against the outrage.

There was no concert of action except that to which a common humanity

impelled the people. Indignation flashed from every eye. Abhorrence

of the Fugitive Slave Bill poured in burning words from every tongue.

The very stones cried out.

In a postscript to this account, May added these comments:

It was pretty generally known throughout the country, that there is

prevalent in this city and county, a strong anti-slavery sentiment,

and, more especially, a deep abhorrance [sic] of the Fugitive Slave

Law. As if on purpose to set this public feeling at defiance, and challenge

us to make it manifest, Mr. Webster declared to an assembly of our citizens

last June, that that execrable law should be enforced here; ay, in the

midst of the next Anti-Slavery Convention, that should be held in this

city. Such a threat was not adapted to allay the rising of an opposite

determination. We are not all here quite so craven, and slavish as to

bow at once submissively to such a brow-beating as he attempted to give

us. His words rankled in the bosoms of a great many. This too was well

known.

Letter from Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith, 6 November 1852. Smith

won election to Congress in November of 1852, and this occasioned an effusive

letter from Douglass that made reference to the “Jerry Level”

(almost suggesting that this was equivalent to the scales of justice),

as well as to “rescue cases” and “Jerry Celebrations”:

My Dear Sir. The Cup of my joy is full. If my humble labors have in any

measure contributed (as you kindly say they have) to your election, I

am most amply rewarded. You are now, thank heaven, within Sight and hearing

of this guilty nation—for the rest I fear nothing. You will do the

work of an apostle of Liberty. May God give you Strength. Your election

forms an era in the history of the great Anti Slavery Struggle. For the

first time, a man will appear in the American Congress completely imbued

with the Spirit of freedom. Here to fore, vertue has had to ask pardon

of vice. Our friends who have nobly spoken great truths in Congress, on

the Subject of Slavery, have all of them found themselves in Straits where

they have been compelled, to disavow or qualify their abolitionism so

as to seriously damage the beauty and force of their testimony. Not so

will it be with you. Should your life and health be spared (which blessings

are devoutly prayed for) you will go into Congress with the “Jerry

Level” in your hand—regarding Slavery as “Naked Piracy”—You

go to Congress, not by the grace of a party caucus, bestowed as a reward

for party services; not by concealment, bargain, or Compromise, but by

the unbought suffrages of your fellow citizens, acting independently of,

and in defiance of party!...You go to Congress, not from quiet nor seclusion—Shut

out from the eye of the world—where your thoughts and feelings had

to be imagined—but you go from the very whirlwind of agitation, from

“rescue trials,” from Womans’ rights Conventions, and from

“Jerry Celebrations,” where your lightest words were caught

up and perverted to your hurt. You go to Congress a Free Man.

The reference to slavery as “Naked Piracy” occurs in a published

letter to the Liberty Party of 15 September 1852 of which Gerrit Smith

was one of the signatories. In this same communication, the Jerry rescue

is referred to as “one of the most important and honorable events

in the history of American liberty.”

Trial of Henry W. Allen, U.S. Deputy Marshal, for Kidnapping (Syracuse:

Daily Journal Office, 1852). From the proceedings of this trial, we learn

of Gerrit Smith’s plan to turn the tables on the U.S. marshal who

arrested Jerry and charge him, instead, with kidnapping according to a

New York state law from 1840. Of course, the “counsels for the people”

(Rowland H. Gardner, district attorney of Onondaga County; Charles B.

Sedgwick; and Gerrit Smith) had no hope of winning this case, but it at

least became a vehicle for challenging the legality of the Fugitive Slave

Act of 1850. It is also noteworthy that a grand jury in Onondaga County

found that there was enough evidence to bring the federal marshal Henry

W. Allen to trial.

This case is the first one of the kind that has been brought since

the Constitution of the United States was adopted. It, therefore, possesses,

on that account, an importance which could not otherwise attach to it.

Henry W. Allen, the defendant, is Deputy U. S. Marshal. As such, a

warrant, issued by Jos. F. Sabin [sic], U. S. Commissioner, for the

arrest of one Jerry, otherwise called William Henry, on the 29th of

September, 1851, was placed in his hands. It was alleged in said warrant

that said Jerry owed “service and labor” to a party in Missouri.

On the next day—1st of October—Allen executed the warrant,

by the arrest of the man Jerry, who was brought by him before Commissioner

Sabine for examination, with a view to deciding whether he should be

returned to Missouri, on the claim set up on the warrant.

Before this examination was concluded, it is well known that Jerry

left for parts unknown, so far as the records of the U. S. Commissioner

show.

Marshal Allen was presented before the Grand Jury of Onondaga County,

at the October session of the County Court, 1851, for indictment under

a law of the State of New York, 1840, to protect the rights of its citizens—or

against kidnapping.

The Grand Jury found a true bill against Marshal Henry W. Allen, under

said Act for kidnapping, in arresting Jerry under the said warrant.

And hence, the case set down for this day, 21st June, 1852, at the

Onondaga Circuit, before Justice Marvin.

Letter of Samuel J. May to Gerrit Smith, 31 August 1854. May refers to

the abbreviated term that Smith spent as a congressman, but the letter

also clearly illustrates how the Jerry Rescue had become woven into the

programming and strategies of the antislavery movement. May is clearly

hoping to have the Jerry Rescue celebration be juxtaposed with a major

antislavery meeting that will involve William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore

Parker, Wendell Phillips, and Lucy Stone, all nationally known figures

in the movement:

While, in common with all your constituents and friends, I lament

that you felt constrained to resign your seat in Congress, I most heartily

rejoice that you have come back to live amongst us—and infuse

into this Community more of your spirit of reform. And, though I have

not heard so much from you, I venture to conjecture that you have found

Congress a hateful place, and can hardly blame you for wishing to get

out of it....

It is quite time that some arrangements should be made for the celebration

of the Rescue of Jerry....I have spoken on the subject to Ira H. Cobb.

He seemed ready to go for the celebration—but intimated, that,

as the 1st of October this year comes on Sunday—the Celebration

had better be postponed or anticipated a day. I replied to him “if

an ox or an ass fall into a pit on the Sabbath day”—who would

not pull him out. It cannot be more unlawful to rejoice in memory of

a good deed, than to do it on the Sabbath day....

The American Anti Slavery Society is to hold its Semi annual meeting

on the 29th & 30th of September. [William Lloyd] Garrison, [Wendell]

Phillips, Lucy Stone will probably be here—and I have also especially

invited Theodore Parker—If they are here, Parker will preach in

my Church Sunday morning—and we shall have an Anti Slavery gathering

somewhere to hear from the other friends in the evening—whether

we have the [Jerry Rescue] celebration proper or not.

Engraved portrait of Gerrit Smith from Speeches of Gerrit Smith in

Congress (New York: Mason Brothers, 1855).

Published letter from Gerrit Smith to John Thomas, Esq., 27 August 1859.

Gerrit Smith announced in this publication his intention not to attend

the annual Jerry Rescue celebration for that year because the former “Jerry

Rescuers” had failed to adhere to the “Jerry level,” or

to have sustained the moral outrage that made them defy the Fugitive Slave

Act. Approximately two months after this declaration was made, John Brown,

with financial assistance from Gerrit Smith, would raid the federal arsenal

at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia.

I have this day received your letter inviting me to preside at the

approaching Anniversary of the Rescue of Jerry, and to prepare the papers

for it. Thankful for this honor as I truly am, nevertheless I am constrained

to decline it. I have presided at all the Anniversaries of this important

event, and written the Address adopted at each of them. But my interest

in them has declined greatly for the last two or three years: and I

am now decidedly of the opinion that it is unwise to continue to repeat

the farce any longer.

The Rescue of Jerry was a great and glorious event. Would God it had

been duly improved! But those who achieved it, and I include in this

number all who cheered it on and rejoiced in every step of its progress,

have, with few exceptions, proved themselves unworthy of the work of

their own hands. We delivered Jerry in the face of the authority of

Congress and Courts; and, as most of us believed, in contempt also of

a provision of the Constitution itself. We delivered him, believing

that there was no law and could be no law for slavery. On that occasion

our humanity was up; and in vain would all the authorities on earth,

even the bible itself included, have bid it down. Our humanity owned

Jerry for its brother: and so did it cling to him, that all the wealth

of the world would not have sufficed to buy it off, or tempt it to ignore

and betray him....

When the day of her calamity shall have come to the South, and fire

and rape and slaughter shall be filling up the measure of her affliction,

then will the North have two reasons for remorse—

First, That she was not willing (whatever the attitude of the South

at this point) to share with her in the expense and loss of an immediate

and universal emancipation.

Second, That she was not willing to vote slavery out of existence.

Then too when, alas, it will be too late, will be seen in the vivid

light of the sufferings of our Southern brethren both black and white,

how shameful and of what evil influence was the apostasy of those “Jerry

Rescuers,” who were guilty of falling from the “Jerry level,”

and casting proslavery votes.

Read

the full text of this letter in Syracuse University Library's

Gerrit Smith Papers.

|