Dust Bowl photographs from the manuscript collection of Margaret Bourke-White.

A selection of material on migrant labor in New York State from the manuscript collection of Central New York social activist Prudence Wayland-Smith (1908-95).

"Grace Lumpkin is among the very few proletarian writers who do not begin with an assumption that a strong belief in a cause excuses any amount of careless writing about it" (Robert Cantwell, "No Landmarks," Symposium 4, no. 1 [January 1933], 81).

"The Cock's Funeral is a story of farm workers in America. These are the beaten, the uneducated, the writhing mass of people who can be driven no further down in life. They have reached the limits of human endurance and, at last, are fighting for their lives. Because of their subjection, they are born into the world vulgar, unwashed, and ignorant. If their language and habits offend, it is not their shame, but America's" (Ben Field, The Cock's Funeral [New York: International Publishers, 1937], 8-9).

"The heat increased; dust storms eddied about the knoll, which grew balder every day in the wind. The cottonwood turned yellow prematurely...not a robust fall gold, but a gray, sickly hue. There was grit on the floor of the house, and in the cupboards on the dishes, in the dresser drawers...grit suspended in the air. It roughened their skins and stung their eyes and tore at their throats. There was grit in their mouths when they ate" (Dorothy Marie Davis, "Dwellers in the Dust," Direction 1, no. 7 [July/August 1938], 10).

"Everybody knows about John Steinbeck's Joads, the "Okies" of "Grapes of Wrath," who followed the harvest in California in a grim effort to keep body and soul together. Through the printed page and the screen the Joad family a few years ago roused nationwide concern over the West Coast's migrant farm worker problem. New York newspapers sent reporters across the continent to travel from crop to crop with the "Okies" and "Arkies" and send back feature stories on conditions in the farm labor camps. What the New York papers did not seem to know was that they need not have gone so far afield. Stories on migrant farm workers were available in their own state. They still are.

"The Imperial Valley lettuce fields, harboring some of the worst labor conditions in California, has [sic] been the scene of so many struggles during the past eight years, all of increasing violence, that the growers prepare for the picking season by organizing their terror in advance. Organization among the workers prior to any protest or demand must be carried on with the utmost secrecy. Underground tactics must be resorted to which can be compared only to the conditions prevailing in Fascist Germany. Any worker participating in the organization of a union is eligible to arrest. As far back as 1930, seven workers were railroaded to San Quentin and Folsom prisons for no other act than seeking to organize the agricultural workers" (Michael Quin, "Blood on the Lettuce," New Masses 10, no. 4 [23 January 1934], 11).

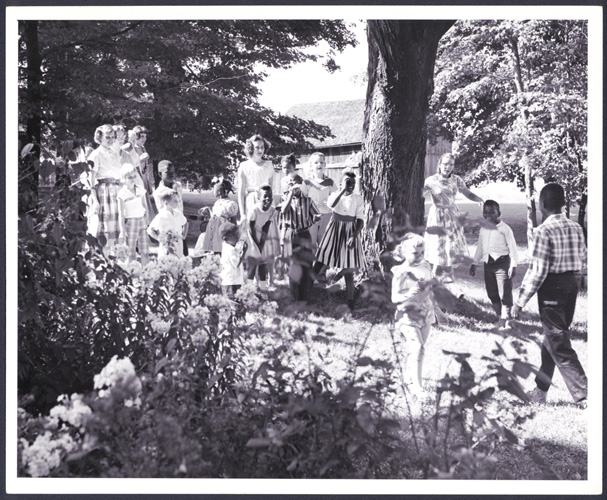

Migrant Committee party for children of the Willows Migrant Camp in Vernon, N.Y., in August 1959 at the Attic House Farm.

"In 1944, there were more than 400 camps for farm workers operating in New York State. Some of these were temporary camps especially set up or protected under the state and federal governments' war manpower programs for workers imported from the West Indies or for members of the Student Farm Corps and Women's Land Army, recruited from within the state from among high school and college students or city vacationists. But the majority were permanent camps-permanent in the sense that they reopen from year to year to house "pickers" brought in from near and far to help get the beans, peas, tomatoes, celery, corn, and other products of New York's rich soil from the fields to the larder" ("How They Live," The Joads in New York [New York: Consumers League of New York, January 1945], 5).

Floral artwork (1967) by Penny Chapman from the Sherrill Migrant Summer School.