4 February - 27 May, 2005

Bird Library, 6th floor

Viewing Hours: Monday - Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

In support of the "If All of Central New York Reads" initiative and the Syracuse Stage production of The Grapes of Wrath, the Special Collections Research Center will display some of its radicalism holdings in literature and art. Along with contemporary critical responses to publication of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, the exhibit will include other, if less well-known, Depression Era novels by Robert Cantwell, Edward Dahlberg, and Grace Lumpkin; an assortment of 1930s cartoons by A. Redfield and Otto Soglow; and a backward look at the uses of art, particularly drama, in the service of revolutionary ideology.

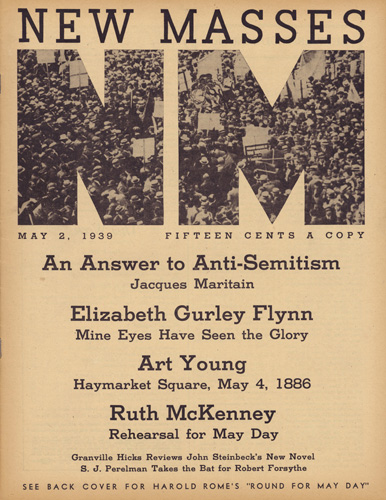

Notes on Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath from the Granville Hicks Papers. Hicks (1901-82) was the literary editor for New Masses, the New Leader, and the Saturday Review of Literature.

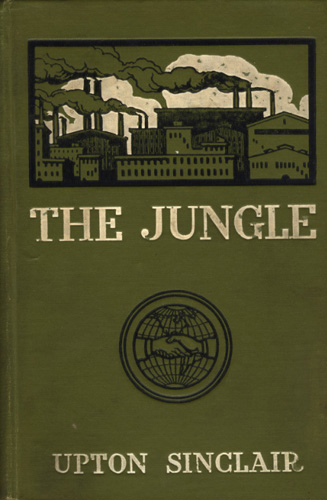

"I feel this book may just possibly do for our time what Les Miserables did for its, Uncle Tom's Cabin for its, The Jungle for its. The Grapes of Wrath is the kind of art that's poured out of a crucible in which are mingled pity and indignation" (Clifton Fadiman, "Books," New Yorker 15 [15 April 1939], 81-83).

"It is, from any point of view, Steinbeck's best novel, but it does not make one wonder whether, on the basis of it, Steinbeck is now a better novelist than Hemingway or Farrell or Dos Passos; it does not invoke comparisons; it simply makes one feel that Steinbeck is, in some way all his own, a force" (Louis Kronenberger, "Hungry Caravan," Nation 148 [15 April 1939], 440-41).

"Between chapters Author Steinbeck speaks directly to the reader in panoramic essays on the social significance of the Okie's story. Burning tracts in themselves, they are not a successful fiction experiment. In them a 'social awareness' outruns artistic skill" ("Okies," Time 33 [17 April 1939], 87).

"Mr. Steinbeck has invention, observation, a certain color of style which for some reason does not possess what is called magic" (Edmund Wilson, "The Californians: Storm and Steinbeck," New Republic 103 [9 December 1940], 784-87).

"I dislike his manner of writing, which I think epitomises the intolerable sentimentality of American "realism." I think he wrecks a beautiful dialect with false cadences; I think he is frequently uncertain about where to end a sentence; I think his repetitiveness is not justified by emotional result; and whereas the funny, niggling coarseness which he jovially imposes on his pathetic migrants may be true to type, it seemed to me out of tone, and to offend against the general conception" (Kate O'Brien, "Fiction," Spectator 163 [15 September 1939], 386).

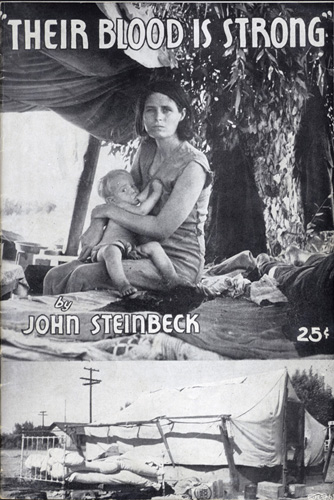

"Last spring the Simon J. Lubin Society of California [dedicated to research and action in matters of concern to California's small farmers, agricultural workers, and consumers] brought out in pamphlet form, under the title Their Blood Is Strong, some newspaper articles Steinbeck had written on the homeless migrants. To compare this pamphlet with The Grapes of Wrath is to gain considerable insight into the problems of the two types of writing. But the point I want to make here is that the pamphlet proves beyond any question that the novel is based on first-hand knowledge and on a carefully acquired knowledge of economic forces" (Granville Hicks, "Steinbeck's Powerful New Novel," New Masses 31, no. 6 [2 May 1939], 23).

"It is difficult to believe what one large speculative farmer has said, that the success of California agriculture requires that we create and maintain a peon class. For if this is true, then California must depart from the semblance of democratic government that remains here" (John Steinbeck, Their Blood Is Strong [San Francisco: Simon J. Lubin Society of California, 1938], 3).

"In an act of naive audacity, in spring 1939 Babb sent four completed manuscript chapters of her novel to Random House, a publisher of such distinction it rarely gave agentless manuscripts a second look. Nonetheless, cofounder and eminent editor Bennett Cerf liked what he saw, mailed her a check, and asked her to come to New York City for the summer to complete the novel. When she finished, what she gave to Cerf, on which he bestowed high praise, is the same work, with only minor alterations, that is featured here. However, whatever grand plans Cerf had for publishing her 'exceptionally fine' novel disappeared the moment The Grapes of Wrath hit the shelves and sold 430,000 copies [in] the next five months. 'What rotten luck,' Cerf wrote her, 'that The Grapes of Wrath should have so swept the country! Obviously, another book at this time about exactly the same subject would be a sad anticlimax!'" (Lawrence R. Rodgers, "Foreword," in Sanora Babb, Whose Names Are Unknown: A Novel [Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004], x-xi).

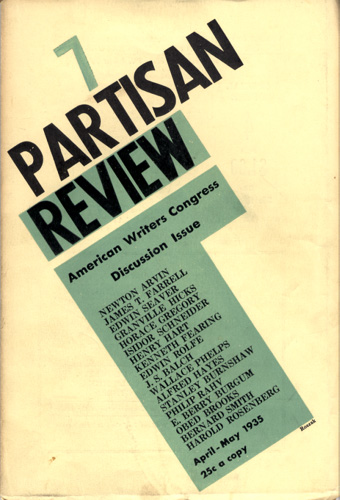

"On the other hand from Mr. John Steinbeck'whose inspired pulp-story, Of Mice and Men, swept the nation like a plague-one expected nothing. It is therefore gratifying to report that in The Grapes of Wrath he appears in a more sympathetic light than in his previous work, not excluding In Dubious Battle. This writer, it can now be seen, is really fired with a passionate faith in the common man. He is the hierophant of the innocent and the injured; and his new book, though it by no means deserves the ecstatic salutations it has received in the press, is an authentic and formidable example of the novel of social protest" (Philip Rahv, Partisan Review 6, no. 3 [Spring 1939], 111).

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) was a novelist and one of the original "muckrakers." Publication of The Jungle in 1906 marked one of the earliest appearances of the radical novel in the United States.

"Steinbeck is a poet. He loves the country, he loves the people, he loves everything that he describes. He will sit down and watch a land turtle crawling up a dusty bank and he knows every move of the turtle's head and feet; he tells it with such a fine humor that he makes the turtle human-as to some extent all living creatures are. He does the same job for a roadside fillingstation or an "eats" joint, for a dog hit by an automobile, for an old woman going out of her mind from exhaustion. Everything is real, everything perfect. At least everything suits me; I wouldn't know how to make it better

"I have come to the age where I know I won't be writing forever. I remember reading how Elijah put his mantle on the shoulders of Elisha. John Steinbeck can have my old mantle if he has any use for it" (Upton Sinclair, Common Sense 8, no. 5 [May 1939], 23).

"That summer I did little public speaking, although I did go to Cambridge to talk about Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath for the benefit of a left-wing bookstore" (Granville Hicks, Part of the Truth [New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1965], 175).