In September of 1839, a Mr. and Mrs. J. Davenport of Mississippi arrived in Syracuse for a visit accompanied by a domestic servant named Harriet Powell. Harriet was a strikingly beautiful woman who was certainly attracting attention in the city. The party had taken up residence in the Syracuse House, the most luxurious of the hotels in the city, and this is where it was learned that Harriet was actually a slave owned by the Davenports. The abolitionists William M. Clarke and John Owen conveyed a message to her at the hotel that they could arrange transportation for her to freedom in Canada if she desired it. Harriet seemed to hesitate, but, upon hearing rumors that she was soon to be sold to a man for the sum of twenty-five hundred dollars and after assurances that the escape could not fail, she agreed to the plan for her deliverance. Clarke and Owen devised a daring rescue involving two coaches, one of whom belonged to Abraham Nottingham of Dewitt. Harriet was transported to the home of a Mr. Sheppard of Marcellus, and then had to be quickly transferred again after the first place of refuge became known. Clarke conveyed her to Gerrit Smith in Peterboro, New York, and then Harriet settled in Kingston, Ontario, residing for a time with Charles and Charlotte Hales. As a footnote to the story of Harriet Powell, it should be mentioned that Mr. Davenport went bankrupt within one year of the escape of Harriet, and Harriet would doubtless have been sold by Davenport in an attempt to salvage his finances had she remained in his household.

Letter from William M. Clarke to Gerrit Smith, 25 October 1839. With this document, William M. Clarke formally transfers Harriet Powell to Smith’s care after having planned and been instrumental in her escape:

I have just received your line by Mr Deny [probably Mr. Federal Dana] and commit to his and your care and to all wise Providence the precious precious Charge that has been for a few short day’s sheltered beneath my humble roof, from the foul soul catcher of our detestable South[.] Oh may the God of the oppressed speed the this interesting refugee from our southern prison-house to a land where slavery is not known[.] I shall be happy to attend the convention at Cazenovia if I can consistently but I do not know as I can[.] If I do not do let me know all I could wish[.]

The articles of Clothing which I have prrocured for Harret I wish you to hand to Mrs J C Jackson and I can obtain them[.] they are article[s] I have borrowed of my sister[.] That God may in great mercy prosper ever exertion in behalf of bleeding humanity is the earnest prayer of Yours in Great haste[.]

Seal with the inscription “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” incorporating the image of a kneeling slave in chains. It was originally designed by English antislavery Quakers in the late 18th century. They invoked the assistance of Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery manufacturer, in its creation. In the 19th century, it became adopted as one of the symbols of the American antislavery movement, and William M. Clarke chose stationery with this evocative emblem upon it.

View of Salina Street showing the Syracuse House on the corner of Genesee Street and taken from the banks of the Erie Canal. The Syracuse House is the hotel where the Davenports and Harriet Powell were staying in the fall of 1839 before Harriet’s escape to Kingston, Ontario, with the assistance of local abolitionists. The reward poster for Harriet Powell also stipulates that Harriet should be returned to the proprietor of the Syracuse House. One Philo N. Rust was the owner, and his death, “the effects of an overnight debauch” in New York, was mentioned in the letter of Charles B. Sedgwick to his wife on 11 April 1851 in this exhibition. Sedgwick, of course, would not have had any respect for a publican who cooperated with a slaveowner.

Letter from James C. Fuller to Gerrit Smith, 3 December 1839. Fuller explains in this communication in considerable detail the differences he has with Smith’s positions on various political strategies: “I meant to give a few ‘hard thumps’ because I thought what thou wrote on the subject of paying Debts was rotten. I think so still and as I believe thou wrote under a ‘thick cloud’ hope ere this the mist is dispelled.” At the conclusion of the letter, though, he finally refers to the escape of the slave Harriet Powell from Syracuse in September of that year:

I hope thou hast no idea that Davenport can obtain Harriet!!! I sent an advertisement of John Bulls for thy perusal respecting her.

Fuller might well have been interested in this celebrated rescue because of his own Underground Railroad activities and the fact that Harriet was sheltered in Marcellus, the town adjacent to his own (Skaneateles). In fact, Fuller’s residence was probably not chosen as a refuge for Harriet precisely because Fuller was notoriously outspoken in his antislavery sentiments. The reference Fuller makes to “an advertisement of John Bulls” probably pertains to an English newspaper advertisement for the return of Harriet, probably very similar in nature to the reward poster for Harriet in this same case. John and Lydia Fuller were English Quakers who had settled in Skaneateles.

Reward poster for the return of the slave Harriet Powell, 9 October 1839. This is the only known copy of this, and it is on loan from the Onondaga Historical Association Museum and Research Center in Syracuse, N.Y. She was described as a “Bright Quadroon Servant-girl, about twenty four years of age, named HARRIET. Said girl was about 5 feet high, of a full and well proportioned form, straight light brown hair, dark eyes, approaching to black, of fresh complexion, and so fair that she would generally be taken for white.” The argument for her return made by Davenport is a fascinatingly perverse one because it was rumored that he was, indeed, planning to sell Harriet for twenty-five hundred dollars, the very sum that he concedes he was offered for her:

In leaving the service of the subscriber [Davenport], she leaves her aged mother and a younger sister, who are devotedly attached to her, and to whom she has ever appeared much attached. It may be proper also to state, that her conduct as a servant, and her moral deportment so far as the same have come to the knowledge of the subscriber, have hitherto been irreproachable. It is believed that she [Harriet] has been spirited away from the service of the undersigned, by the officious and persevering efforts of certain malicious and designing persons, operating through the agency of the colored people of Syracuse, at which place he had been induced to spend a few days. The subscriber would further add, that he has refused several importunate offers of $2,500 for said girl, for the sole reason that he would never consent to part her from the other members of her family, and that it is chiefly with [t]he hope of restoring her to her aged mother and sister, who will be plunged in sorrow at the separation, that this notice is [pu]blished. The above reward of Two Hundred Dollars will be paid to any person who will deliver said girl to the proprietor [of the] Syracuse House, in Syracuse, or one hundred D[ollars to] any one who will give such information as shall lead to her [arrest.]

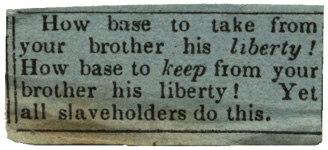

Letter from James C. Fuller to Gerrit Smith, 4 March 1842, with an antislavery stamp used to seal it. Several of the letters from James Fuller to Gerrit Smith have such stamps affixed to them that carry antislavery mottoes such as the one copied here. Just as stationery with the seal of the supplicating slave in chains was available for sale to support the cause, so too were these diminutive stamps with their succinct but intense messages.

Letter of Charlotte Hales to Gerrit Smith, 3 January 1841. After the successful relocation of Harriet Powell to Kingston, Ontario, Hales writes to Smith to report on Harriet’s well-being and to inquire about any news of Harriet’s mother or sister:

Although a stranger I am persuaded I need not apologise for addressing you. Harriet Powell is residing with me and has done so since she came to Kingston. She is most anxious to hear of her Mother and sister, and particularly wishes you would write to the former: if you could obtain any information respecting them and forward it to Harriet, the poor girl would be most thankful. She received your letter of Decr. for which she is much obliged, she desires me to tell you that she is quite contented & very comfortable in her present situation. I am teaching her to read, and if she continue with me I may teach her writing. I find her a girl of good moral principles, but very ignorant concerning the things wh. [which] belong to Salvation; I am happy to say she seemed willing to receive instruction and as she now enjoys many religious privileges I trust she will be truly converted to God. We have heard many reports of Mr. Davenport’s determination to get her again if possible, we also understood men were employed to kidnap her, I scarcely think the latter is true, but it was sufficient to put us on our guard, and we do not allow her to go out unprotected. Harriet begs me to give her very kind love to you, Mrs. Smith and Laura & any of her kind friends you may see; she wishes me to tell you that she feels very grateful to you all, for your great kindness in assisting her to obtain her freedom. She finds a great difference between the winter here & in Mississippi, but is likely to stand it well.

Harriet says she has not any wish to return, and as long as this is the case we are resolved to protect her.

I hope you will be kind enough to write to Harriet as soon as you can obtain any satisfactory information. With best wishes for your success in your labour of love