Virtually all the facets of the print world were brought to bear as both a means of disseminating their message and generating sources of funding. The examples include pamphlets, book-length fugitive-slave narratives, letters associated with Frederick Douglass’s newspaper (the North Star), and a first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as well as correspondence that is directly related to the creation and marketing of these published pieces.

Letter from James C. Fuller to Gerrit Smith, 15 October 1841. Fuller describes in this letter some of the early settlements in Ontario that became refuges for escaped slaves. His mention of Austin Seward taking up residence in the area known as the Queen’s Bush is not exactly correct; it was actually the Wilberforce Settlement. Steward’s own account appears in the book Twenty-Two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman, and this volume is included and described in this case. In this same letter, he alludes to a whip and handcuffs from a Mississippi plantation that he wanted to secure as artifacts (and of which he did not want Smith to be aware) to be used in his antislavery lectures. The Sam who is mentioned is the head of the household that was liberated by Fuller on Smith’s behalf.

I have taken my Pen on account of the information concerning the two Slaves thou made mention of with the view of informing thee that I learn from Hiram Wilson that the Canadian authorities now put on the same footing all men who are inclined to go and settle on the Queens Bush, and they have a free donation of fifty acres of land with liberty to buy 50 other acres. The conditions on which the Donation is made are that the accepter must make it appear that he has means on which to subsist the first season, and that he must in a given time (I think three years) clear and cultivate one third of the 50 acres....Austin Steward of Rochester and other Cold [colored] men of that City are well pleased with the location on Lydenham River, and this day I suppose Hiram and others will make a contract for the most desirable lot of the two at the head of Navigation....It should be known that the Queens Bush is good land, and not heavy timbered; it is as I understand dry sandy loom, and of course easy of Cultivation.

...When Sam and I parted he promised to bring me from Mississipi a Whip that had been actually used on the Plantation and also a pair of Cables handcuffs &c and I measured thy Corn by my bushel, apprehending that there is not much difference between men and I therefore told him not to let thee know that he had such things for I did not want thee to be tempted with coveting other mens goods.

[No image available]

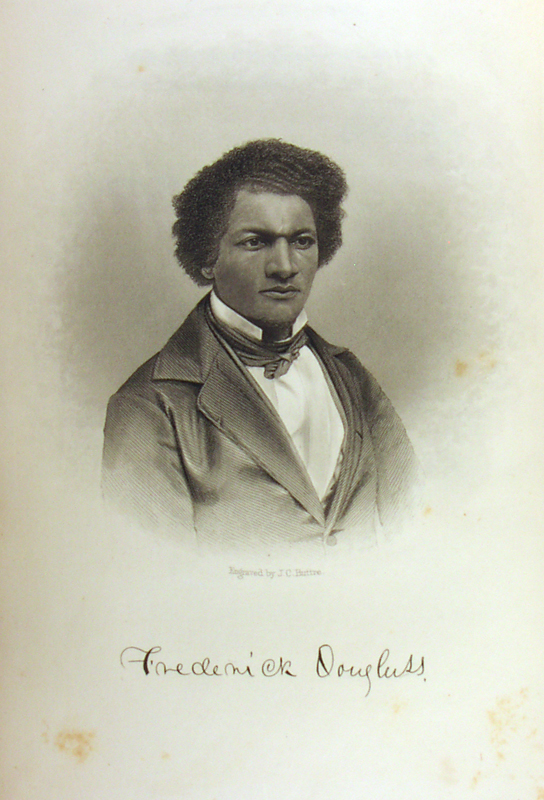

Letter from Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith, 16 December 1856. Douglass thanks Smith for his continued support of his paper, the North Star, and refers to the “Jerry Rescue Resolutions” that were prompted by the annual celebrations surrounding this event:

Please accept my thanks for your generous donation of twenty dollars—I am happy to know by this expressive Sign, that you still desire to See my paper Afloat. You ought to, for you have watched over it with Almost Paternal Interest. No, My Dear Sir. I am not a member of the Republican party. I am still a radical Abolitionist—and shall as ever, work with those whose Antislavery principles are similar to your own. My English friends, are just now dealing with me for my Jerry Rescue Resolutions. They think you were altogether too tolerant of my “Abominable Sentiments.” I am writing an article though not a formal reply to Strictures made upon those resolution—yet a sort of imbodyment of the Sentiments uttered by me at the “Jerry Rescue Celebration.[”]

Please make my best respects to Mrs Smith. Accept my Sincere Thanks for the donation of twenty dollars.

Twenty-Two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman by Austin Steward (Canandaigua, N.Y.: published by the author, 1867). This volume was published to help raise funds after the Civil War for Steward’s benefit and displays an engraving of a fugitive slave who has just cut his own throat on a ship on the Hudson River rather than be returned to slavery in the South. The caption reads “I walked hastily forward and turned round, when, Oh, my God! what a sight was there! He still held the dripping knife with which he had cut his throat.”

Read the full text of this work in the "Documenting the American South" digital collection at the University of North Carolina.

The masthead from the North Star of 11 February 1848 (volume one, number seven), the abolitionist newspaper edited by Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. Its motto affirms that “RIGHT OF OF NO SEX—TRUTH IS OF NO COLOR—GOD IS THE FATHER OF US ALL, AND WE ARE ALL BRETHERN.” In the letter to the left from 16 December 1856, Douglass thanks Gerrit Smith for a donation directed to support of his paper: “Please accept my thanks for your generous donation of twenty dollars—I am happy to know by this expressive Sign, that you still desire to See my paper Afloat. You ought to, for you have watched over it with Almost Paternal Interest.”

Letter from James C. Fuller to Gerrit Smith, 19 January 1847. Fuller explains that he is continuing to send antislavery pamphlets to slaveholders in North Carolina. The tract that he has been using is Alvan Stewart’s A Legal Argument before the Supreme Court of the State of New Jersey at the May Term, 1845, at Trenton, for the Deliverance of Four Thousand Persons from Bondage (New York: Finch and Weed, 1845). He is even advocating that it be reprinted from its stereotype plates:

I replied that if N C Yearly meeting [of the Society of Friends, or Quakers] would give 100 [copies] to Slaveholders that I would give 100 for that object, and another 100 to circulate amongst friends, this proposal was made in consequence of a friend sending me word that that he had received the Argument assuring that it had done good service....

...It is to me matter of regret that Stewarts book is out of print. I suggested to Alvan the making a tract of pages 30 to 34. I have an application at this time from N C for a further supply of the Argument which cannot be met. The Book ought to be reprinted, Stewart says the Stereotyped plates may be used by any persons free of cost—that the work can be thus obtained at a cost of three cents. I look on parts of it as superlatively good, as a whole admirably calculated to do great good.

Letter from Samuel J. May to an unidentified recipient, 26 July 1851. May directs a box of clothing to Oswego that is intended for fugitive slaves in Canada. While this reference could conceivably have been used as code for actual fugitive slaves, this letter seems deliberately focused on the basic supplies required by blacks in their new Canadian environment. The allusion to “publishing a series of articles in Douglass’ Paper” “respecting the condition and prospects of the fugitives in Canada” doubtless refers to the North Star published by Frederick Douglass.

Yesterday I sent to Oswego, care of Mr John B. Edwards a box of clothing for fugitives in Canada—to be sent to you at St Catharine’s by the first safe conveyance, without expense to you.

The box was received from the Country a few weeks ago, and I have not thought it worth while to open it. I wish you would acknowledge the receipt of it—and the amount and value of the contents—

You will use your own discretion in the distribution of these clothes—So bestow them as to make them do the most possible good—and let me know what kinds of clothing the fugitives most need.

I should be much obliged to you if you have any valuable information respecting the condition and prospects of the fugitives in Canada, if you would give it to me at your earliest convenience—for I am about to commence publishing a series of articles in Douglass’ Paper on the subject[.]

The first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Boston: John P. Jewett and Co., 1852). The volume in this case is volume one from the set that is described in the circular as “the edition in 2 vols., bound in cloth, best library edition” to be sold at a retail cost of one dollar and fifty cents.

Letter from John P. Jewett to Gerrit Smith, 27 November 1852. Jewett, the publisher of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, announces to Gerrit Smith that he is about to publish the volume in an edition of one million copies. His letter is, in fact, written on the back of the circular that publicizes this and other editions of the work. At the conclusion of the letter, Jewett also congratulates Smith on his election to Congress:

You will remember to have dined at my house some years since when I lived in Salem, & since my removal to Boston you have probably seen my name in connection with the Anti Slavery Literature of the day & more recently as the publisher of that great Book Uncle Tom[’]s Cabin. I know that you will be pleased to see by this circular that we are about to publish it for the million for 37½ cts & also for the Upper 10th in an elegant illustrated form....Nothing has so rejoiced my heart since the election of my friend [Charles] Sumner to the Senate, as your election to the house. I thank God & take fresh courage. Some good men & true will be in our National Councils.

The circular explains that “millions will now read it, and own it, and drink in its heavenly principles, and the living generations of men will imbibe its noble sentiments, and generations yet unborn will rise up and bless its author, and thank the God of Heaven for inspiring a noble woman to utter such glowing, burning truths, for the redemption of the oppressed millions of our race.”

Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Gerrit Smith, 25 October 1852. Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, appeals to Gerrit Smith, out of all the antislavery activists of her acquaintance, as the person who may be best positioned to “supply facts & statistics” to counter the suggestion that she has exaggerated the evils of slavery in her book:

I have been solicited both in England & this country to give some forty or fifty pages of notes in addition to my book to supply facts & statistics to show that it is not an overdrawn picture of Slavery—I am pressed for time it being thought desirable that it should appear in England during the height of the Uncle Tom fervor. The whole civilized world seems now to have called up slavery on trial & the slave holding defenders are beginning to make their replies in England. The pamphlet against Uncle Tom’s cabin by a South Carolinian has been republished in England & many papers there are beginning to speak of it as “overdrawn” “highly coloured,” &c[.] The whole antislavery controversy will be gone over on English ground & the earlier we supply a firm basis of facts & statistics the better.

The supplementary material that Stowe is seeking would ultimately become The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which according to the circular (see above) sent to Gerrit Smith by John P. Jewett, the publisher of the book, was “a complete refutation of some charges which have been made against her on account of alleged overstatements of facts in Uncle Tom. It will make a pamphlet of about 100 pages, double columns, and will present original facts and documents, most thoroughly establishing the truth of every statement in her book.” The cost of this was to be twenty-five cents. Of course, the “original facts and documents” were precisely the ones Harriet Beecher Stowe was soliciting from Gerrit Smith.

Letter from Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith, 24 March 1852. A fund-raising project of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society was a festival held in the spring of 1852, and Gerrit Smith’s participation in it was keenly appreciated, as this letter demonstrates:

I thank you warmly, for attending our Festival. Your visit to Rochester has done good both to the Cause of temperance and to Antislavery. The festival was highly successful, and has left a good impression. The receipts amount to more than four hundred dollars—and I believe, that the expenses do not exceed one hundred dollars. You may well suppose, that Julia Griffiths, is highly pleased with the result.

...In the accounts which I have given of the Convention, in my paper, I have thought proper to leave out all mention of the Fosters. I am persuaded that there is a desire to provoke me into a controversy with them. They accuse me now, openly, of having Sold myself to one Gerrit Smith Esq and to have changed my views—more in consequence of your purse than your Arguments! These things are disagreeable but they do not move me. A consciousness of my own rectitude affords me abundant repose, and enables me heartily to despise these assaults.

Portraits of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and William Seward from the book.

Autographs for Freedom edited by Julia Griffiths (Auburn, N.Y.: Alden, Beardsley, and Co., 1854). This compendium of short abolitionist pieces was published as another fund-raising enterprise by the Rochester Ladies’s Anti-Slavery Society, of which Griffiths was the secretary. In the preface to the work, Griffiths thanks the assemblage of authors “who have contributed of the wealth of their genius; the strength of their convictions; the ripeness of their judgment; their earnestness of purpose; their generous sympathies; to the completeness and excellence of the work; and we shall hope to meet many of them, if not all, in other numbers of ‘The Autograph,’ which may be called forth ere the chains of the Slave shall be broken, and this country redeemed from the sin and the curse of Slavery.” Frederick Douglass also takes this impassioned stance in this volume: “We plead for our rights, in the name of the immortal declaration of independence, and of the written constitution of government, and we are answered with imprecations and curses. In the sacred name of Jesus we beg for mercy, and the slavewhip, red with blood, cracks over us in mockery.”

Letter from Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith, 14 August 1855. Douglass discusses the effusive dedication of his book entitled My Bondage and My Freedom (New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1855) to Gerrit Smith:

It would have been quite compensation enough to know that the dedication of my Book afforded you pleasure. That dedication was inserted not to place you under obligations—nor to discharge my obligations to you, but rather to couple my poor name with a name I love and honor, and have it go down on the tide of time with the advantage of that name. Never the less, I gratefully accept your draft for fifty dollars. I do not know, just yet, what use I shall make of it. I am ever disposed to prefer the useful to the ornamental, and shall no doubt find some useful purpose to which I may properly devote the money.

My family are well and join me in kind regards to you and yours.

I leave home tomorrow on a four weeks Campagn through Niagara and Orleans Counties. I shall try to uphold the great principles of freedom, as laid down by yourself, and Mr Goodell at the Radical Abolition Convention.

Letter from Jermain Loguen to Gerrit Smith, 23 March 1859. Loguen comments on the character of a fugitive slave who has apparently appealed to Smith for assistance but also informs Smith of his intention to publish what would become The Reverend J. W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman: A Narrative of Real Life (Syracuse: J. G. K. Truair and Co., 1859). Loguen is clearly hoping that Smith will help subsidize such a publication, just as he had done for many others in the antislavery movement:

I have your letter, in regard to William Smith. I did not write the note that you send, with your letter, & I know nothing about it, but I know it to be bogus,—I have seen the young man,—he came to us as a fugitive some year or two ago.—I do not regard him as true, still I know but little about him....

I am trying to get out a book. What think you of it. I hope you will feel friendly to the idea. We need Something to helpe us to take care of the many poor, that are calling on us for helpe—We have a large family to care for, at the same time—

Letter from Samuel J. May to Gerrit Smith, 10 June 1869. May conveys in this communication the plans for publishing Some Recollections of Our Antislavery Conflict (Boston: Fields, Osgood, and Co., 1869):

Last week I signed an Agreement with Messr Fields and Osgood respecting the publication of my Anti-Slavery Recollections and sent them matter enough for 300 pages & more. I also agreed to be in Boston on the 26th at which time they will have a considerable quantity of proof for me to revise—

I must now hurry up the completion of what remains to be written—and I find there is more of it than I expected.

He also commented that there were specific topics on which he wanted to confer with Smith: “I wish very much, to read to you some portions of what I am now writing about the conduct of the Churches” [with respect to the antislavery movement]. This copy of the volume was presented to a previous owner of it by the daughter of Samuel J. May.

A wholesale receipt issued by the Wesleyan Book Concern, 60 South Salina Street, Syracuse, 14 July 1856. One hundred copies each are being ordered of titles that are being abbreviated as Slavery a Sin, Sanctuary of Sin, Nations Peril, and Sumner’s Speech. The last item mentioned is probably The Crime against Kansas. Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts (New York: Greeley and McElrath, 1856). Sumner’s oration was delivered on 19 May of 1856, and it was the one that occasioned the brutal beating he received on the floor of the Senate two days after its delivery. Partly because of the notoriety of this attack, a million copies of the speech were printed within weeks of its delivery.

Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (Auburn: W. J. Moses, 1869). This wonderful local tribute to one of the heroes of the Underground Railroad was written by Sarah H. Bradford of Geneva, printed by W. J. Moses in Auburn, and the frontispiece of Tubman in her outfit as a scout during the Civil War as its frontispiece was engraved by J. C. Darby of Auburn. In the introduction, we learn that subscriptions were raised for the publication of the volume and for Tubman’s benefit, and that Gerrit Smith made one of the most substantial of these. William H. Seward also facilitated the purchase of a home for Tubman in Auburn. A letter from Frederick Douglass in the book juxtaposed his own antislavery role with that of Tubman’s:

You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation. I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior labors and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them. The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You on the other hand have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day—you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt “God bless you” has been your only reward.

The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1872) by William Still. According to an account in this classic volume, a party of six men and women fled from slavery in Loudon County, Virginia, in a carriage and by horseback on Christmas Eve in 1855. The group was confronted by “six white men and a boy” near the Cheat River in Maryland, having traveled about one hundred miles from their starting point. The fugitives revealed that they had pistols and convinced their assailants that they were quite prepared to “spill blood, kill, or die.” The engraving by C. H. Reed to which this volume is opened depicts this dramatic scene. Those four individuals in the carriage were able to proceed, but the ones on horseback were probably captured. Upon their arrival in Syracuse, Frank Wanzer, the leader of the group, was married to Emily Foster, another member of the party, by the Reverend Jermain Loguen. These four ultimately made their way to freedom in Toronto according to family traditions. This book was published after the Civil War in order to raise funds for William Still, the leader of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia.

Circular of the African Aid Society, Organized in Syracuse, Sept. 8, 1857. The Reverend Samuel J. May initially hired William Brown, the author of this circular, as an agent to assist with fund-raising for the Fugitive Slave Society in Syracuse. Upon investigating his background, however, it became clear that Brown was merely an opportunist, and he was dismissed. In an extraordinarily bold way, however, Brown created his own fictitious African Aid Society and had this piece printed in order to promote it. This is the only known copy of this document. The members of the legitimate Fugitive Slave Society led by the Reverend Samuel J. May were ultimately obliged to advertise in local papers that Brown was soliciting money fraudulently.