Changing Hands: Ownership Erasures in Rare Books

by Irina Savinetskaya, Early to Pre-20th Century Curator

Books tend to move around. Many books in the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) traveled thousands of miles to get here. Before finding a home at SCRC these books led exciting lives of their own, passing through the hands of diverse individuals and kept by institutions for decades and sometimes centuries. Their histories are integral to what makes these materials unique and special. Examining their provenance allows us to uncover the exciting histories hidden within them.

Historically, there have been many ways to mark ownership of a book, including with the help of customized book bindings, book plates and inscriptions. Before the 19th century, most books were sold in plain paper wrappers. The new owner would bring the book to a bookbinder, who would customize it according to the owner's preferences and budget. Once the book was bound, the owner could commission a bookplate. Common from the 16th century onward, the bookplate is a label typically attached to the book's inner cover to record its ownership. Intricately designed, the book plate can feature the owner’s name or initials, motto, coat of arms, and other identity markers.

Many books at the SCRC showcase layers of ownership marks. In some cases, the distinctive marks left by earlier owners were erased by the subsequent keepers. Following are a small selection of such attempts to erase ownership. Two books in this selection come from the library of Jan Maria Novotny (1898-1986), a Czech economist and bibliophile, who emigrated to North America in the late 1940s. Syracuse University acquired his library in 1961.

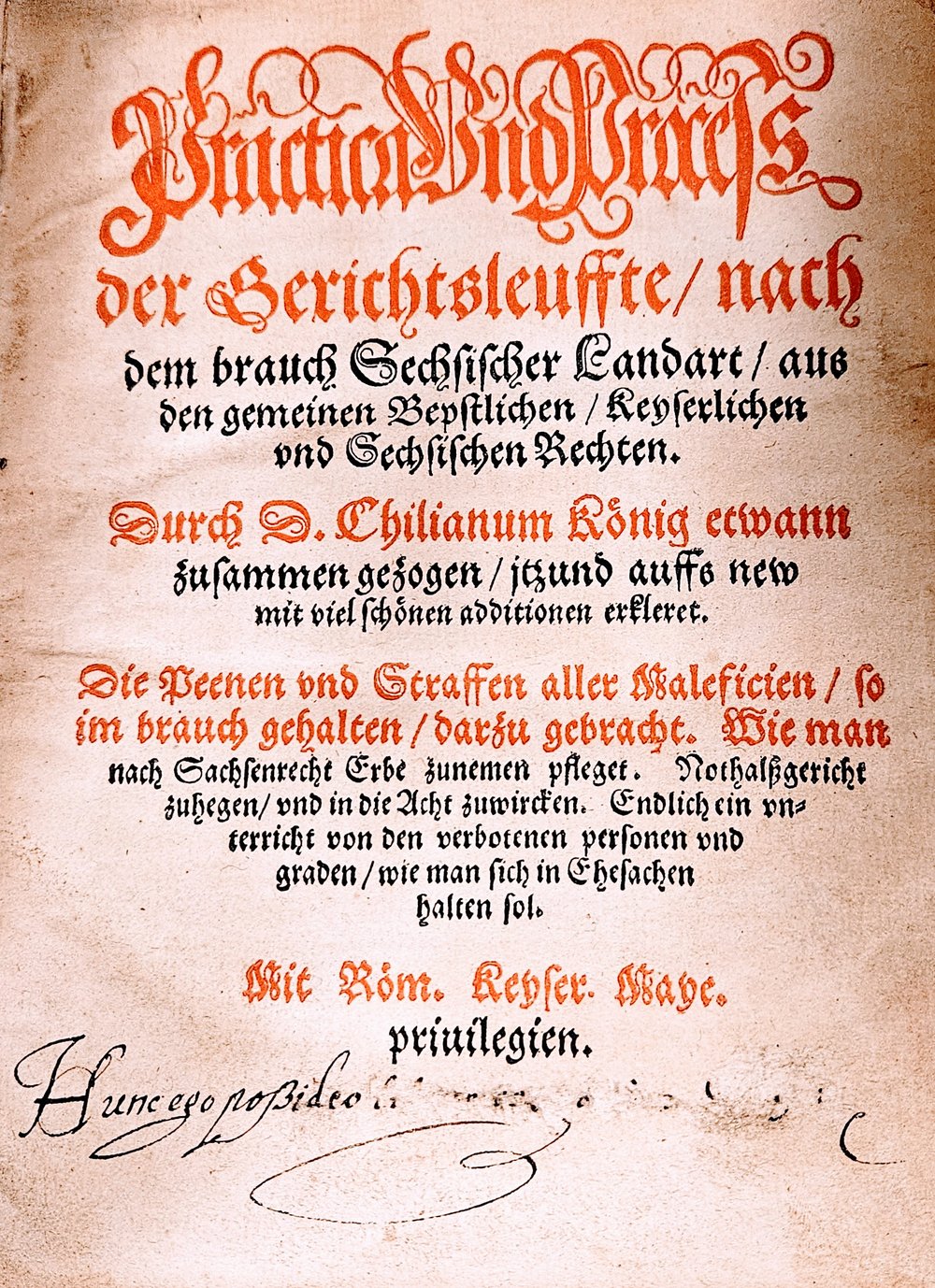

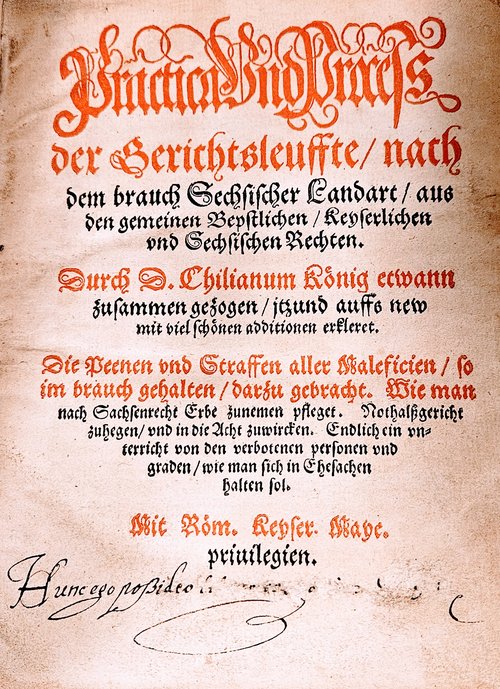

In this first example, an owner left an inscription on the bottom of the title page in Latin “Hunc ego possideo …,” which can be translated as “This I own…”. The name of the owner was scratched out by a subsequent keeper of the book.

Chilianus König, Practica und Process [Leipzig, 1572]. Rare Book and Printed Materials Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

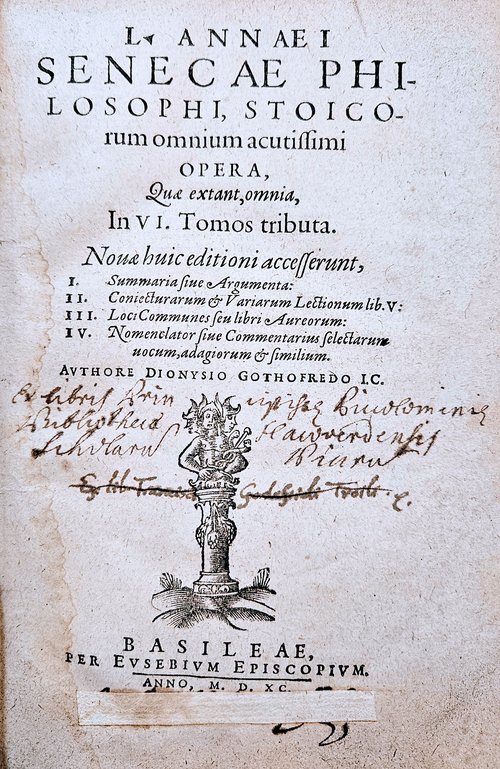

In this next example, not only the name of a previous owner has been crossed out, but a piece of paper was glued over another ownership inscription on the bottom of the page:

L. Annaei Senecae philosophi (Basel, 1590). Rare Book and Printed Materials Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

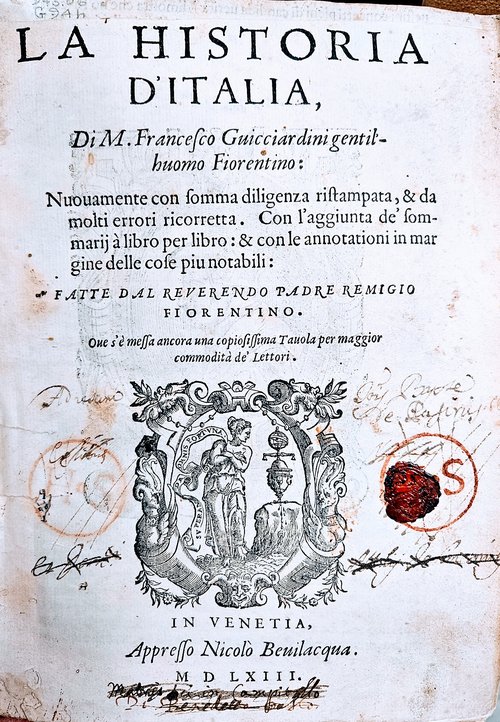

Layers of ownership identifiers can be seen on the title page of SCRC’s copy of the 1563 edition of Francesco Guicciardini’s La Historia d’Italia. There are at least four distinct ownership signatures (three of which are crossed out), and a wax seal.

Francesco Guicciardini, La Historia d’Italia (Venice, 1563). Rare Book and Printed Materials Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

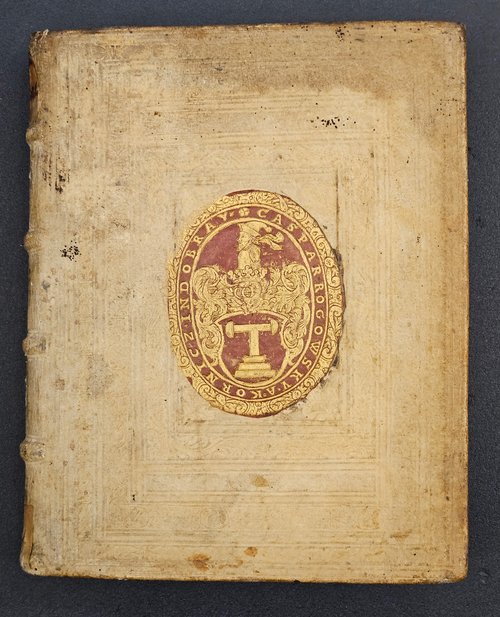

Rebinding books was another common way of erasing ownership. One of the owners of this book, a seventeenth-century bibliophile Caspar Rogowsky von Kornitz of Dobrau, chose a less costly way of re-marking ownership: he glued a leather label with his supralibros (i.e., a coat of arms or monogram indicating book’s ownership) over an earlier binding, possibly containing a previous owner’s ex libris:

Erasmus Reinhold, Prutenicae tabulae coelestium motuum (Wittenberg, 1585). Rare Book and Printed Materials Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

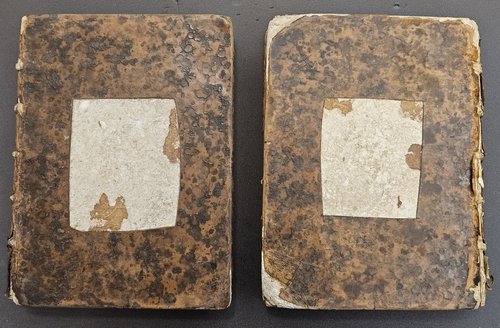

This last example shows another resourceful way of erasing ownership. A previous owner apparently cut out entire pieces of the binding on both volumes of SCRC’s copy of Jean Crasset’s Histoire de l’Eglise du Japon. It was most probably done to remove an earlier supralibros:

Jean Crasset, Histoire de l'eglise de Japon (Paris, 1689). Rare Book and Printed Materials Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

Delving into the obscured struggles for book ownership offers a glimpse into the complex narratives of the books’ journeys through different hands and epochs. The ownership marks found in these materials prompt us to celebrate them not merely as repositories of information but also as unique objects with their own histories.