Charles Eisenmann’s Circus Photography and the Cartes de visite Collection

May is National Photography Month. Over the course of this month, we will be highlighting special collections and University Archives materials that specifically relate to the history of photography. This week, we highlight a research post from one of our graduate student workers.

By Aisha Pierre, Reference Assistant

As a museum studies grad student, I have partaken in several fantastic opportunities to attend networking workshops and conferences, meeting incredible professionals in the field. The more networking opportunities I experience, the more I realize the importance of business cards, and how a simple design can help make an impression. This semester, I am taking “Material Identification” (MUS 500), and our first lecture centered on photography processes. For another one of our lectures, we learned about cartes de visite (cards of visit), which were patented by French photographer Andre Adolphe Eugene Disderi in 1854. Imagine during one of these networking events if I handed a potential employer a small 2 ½ by 4 inch card with a photograph of myself dressed in my Sunday best, staring straight ahead, with no emotion on my face. There is no doubt about it, that would make a lasting impression.

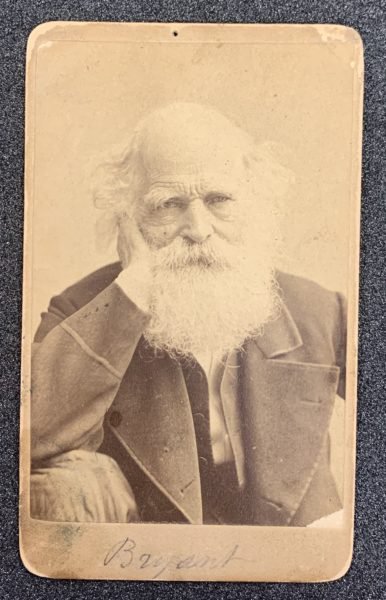

William Cullen Bryant, 19th century American poet and editor of the New York Evening Post. Cartes de visite Collection.

Initially, only those who could afford the cost of photographs were having their pictures taken in photography studios. As photographs become more easily accessible, more photographers took advantage of their audiences’ interest in the new medium and created and marketed an affordable souvenir. At SCRC, we have a Cartes de visite Collection that consists of one small rectangular box with a total of 322 images. The photographs are grouped together into protective sleeves that are ordered alphabetically by the photographer and geographic location. Because of their size, many cartes de visite were stored into albums, and depending on who the subject of the image was, the card could be traded and added to different collections.

To create the cartes de visite, a collodion wet-plate process is used, and printed on albumen paper. First, paper is washed with sodium chloride and fermented egg whites that are mixed with acetic acid. Once the paper has dried, it is dipped into silver nitrate and water, which makes the surface sensitive to UV light. Once dry, the paper is placed into a frame under a negative and exposed to UV light. To secure the image to the paper, it is washed with water to remove any lasting salts. The photos are then secured to thick card stock with contact information for the photographer on the back.

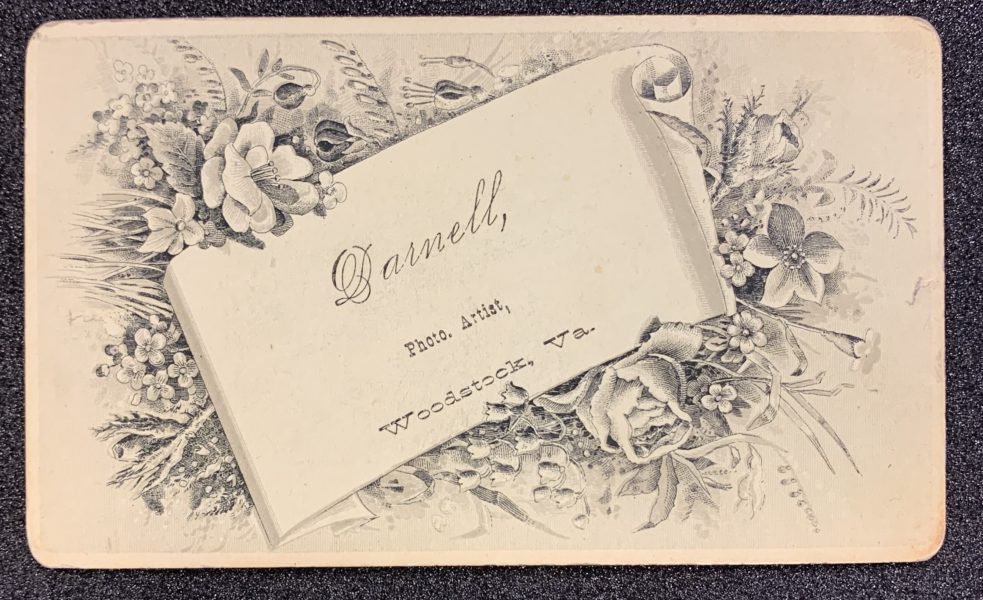

Photographer’s information on the verso of a carte de visite. The card reads "Darnell, Photo. Artist, Woodstock Va." Cartes de visite Collection.

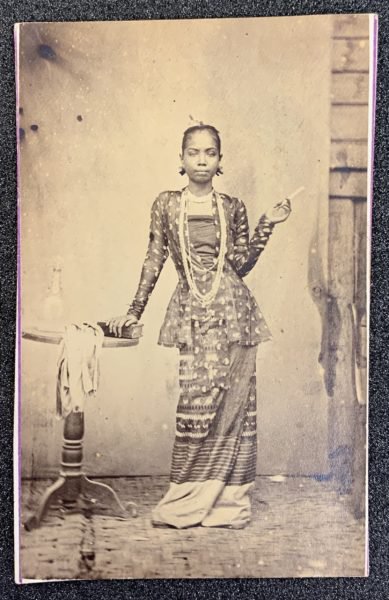

During the 1880s, cartes de visite were superseded by cabinet cards. These were typically 4 inches by 6 inches and received their name because they were the perfect size to fit into a cabinet. With cabinet cards, people were able to collect photographs of noteworthy people, including actors, writers, and politicians and display them publicly in their homes. Although cabinet cards and cartes de visite were popular at different times, their function and subject matter did not largely differ from one another. In the Cartes de visite Collection, there are several photographs of indigenous people and travel photographs from Singapore, Egypt, and China. European and American photographers made these images readily available, as their clients were becoming interested in the appearances of different cultures. In her book titled, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World, author Deborah Poole discusses how the relationship between the subject and the photographer of these photos at times were strained, and this uneven power dynamic often meant that the stories behind the images could be manipulated by the photographer.

Malay woman, standing. Cartes de visite Collection.

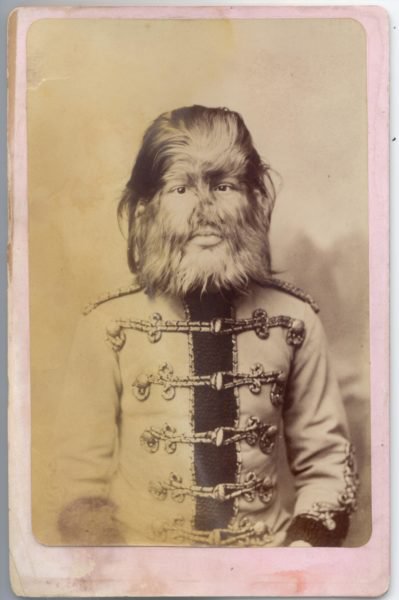

The issue of stories being modified among cartes de visites continues with the Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs. The SCRC collection consists of over one-thousand cartes de visite portraits of circus performers (there are also cabinet cards in this collection), including those from the P.T. Barnum and Bailey Circus. Charles Eisenmann emigrated from Germany in 1870 and owned a photography shop in the Bowery area of New York City. It was in New York that he discovered his interest in circus performer photography. Eisenmann opened his shop to the performers to help promote their acts in the shows.

Charles Eisenmann publicity cabinet card of Jojo the Dog Faced Boy. Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs.

During the Victorian Era, these performers were popular subjects because people were fascinated with admiring – more like gawking – at the physical abnormalities of the circus entertainers. Each performer had an elaborate backstory arranged by their employer that was used to spark excitement in the audience. For example, the famous Jojo the Dog Faced Boy’s circus backstory recounted how he was allegedly discovered in Russia living in a cave before being civilized by Barnum. Jojo’s real name was Fedor Adrianovich Jeftichew and he had hypertrichosis, which causes an excessive amount of hair to grow all over the body. Although the Becker collection has many photographs of performers with real birth defects, like Fedor, many of the images were staged by Eisenmann to depict abnormalities that were not genuine. Some images depict people with three or four legs, which Eisenmann would have staged using props in his photography shop. Eisenmann’s carefully composed photographs of Jojo and other performers brought audiences to the circus and helped people like P.T. Barnum make a fortune.

It has been fascinating to look through the various historic photographs within these collections and see how visiting cards quickly took on the form of souvenir and trading cards in a short period of time. Viewing the cartes de visite and cabinet cards, I have also been able to witness how subjects of photography changed due to the interests of the public and how photographers helped shape how individuals were presented to the public through their own lens. During this time of social distancing and shut downs as a result of COVID-19, I highly encourage visitors to view the entire Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs on SCRC Online.

The Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs (Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and the Cartes de visite Collection (Cartes de visite Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Additional Sources:

Gaffney, Dennis. “Antiques Roadshow.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 9 Jan. 2006, www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2006/1/9/who-were-circus-freaks/.

George Eastman Museum. “The Albumen Print- Photographic Processes Series- Chapter 6 of 12.” YouTube, 12 December 2014. Web. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6JDfdHWBVG4.

“Homepage: George Eastman Museum.” George Eastman Museum, www.eastman.org/.

Kennel, Sarah, et al. In the Darkroom: an Illustrated Guide to Photographic Processes before the Digital Age. Thames & Hudson, 2009. Print.

Poole, Deborah. Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1997. Print.

Volpe, Andrea L. “The Cates de Visite Craze.” The New York Times, 6 August 2013.