Maija Grotell: Revolutionary Craft in 20th Century America

By Tiffany Miller, Reference Assistant

Otherwise known as the “Mother of American Ceramics,” Maija Grotell was a prolific and influential ceramist and educator. She was a revolutionary figure in the ceramics world. Born in Helsinki, Finland in 1899, Grotell became a naturalized American citizen in 1934 after moving to the States to pursue her career in ceramics. Grotell’s multi-disciplinary art background helped her craft innovative designs and glazes, techniques that revolutionized the ceramic industry. In addition to these techniques, her glazes were researched and used on color-glazed bricks as a color guide and reference model, which are still widely used in the architecture field today.

I took an American Ceramics course in the spring of 2020 with the Paul Phillips and Sharon Sullivan Curator of Ceramics, Garth Johnson, at the Everson Museum of Art. In the course, I learned about Grotell and her works along with the history of the Ceramic Nationals. Instated by former director of the Everson, Anna Olmstead, the Ceramic Nationals was an annual competition and exhibition of ceramics made by leading ceramists of the twentieth century. Works would be judged and sold at the event. This event was unique only to Syracuse at the time. Grotell was once admired all over the world for her innovative designs and glazes and she became known for participating in the Ceramic Nationals competitions every year between 1933 and 1960. I became fascinated with her works as I learned about types of glazes, and wanted to know what made her pieces so revolutionary. What better place to do that research than in Syracuse, where Grotell is represented at Syracuse University and at the Everson Museum of Art? The Maija Grotell Papers at Syracuse University’s Special Collection Research Center contain a large collection of her designs, catalogues of her pieces, correspondence with colleagues and museums, and photographs of her work that I have reviewed in order to analyze how and why she became so popular. She is largely forgotten today, but taking a look into her captivating styles and the industry connections she made on her own will hopefully captivate others as she has captivated me. In addition to her papers at SCRC, the Syracuse University Art Museum permanent collection contains six ceramics by Grotell, including two A-grade pieces.

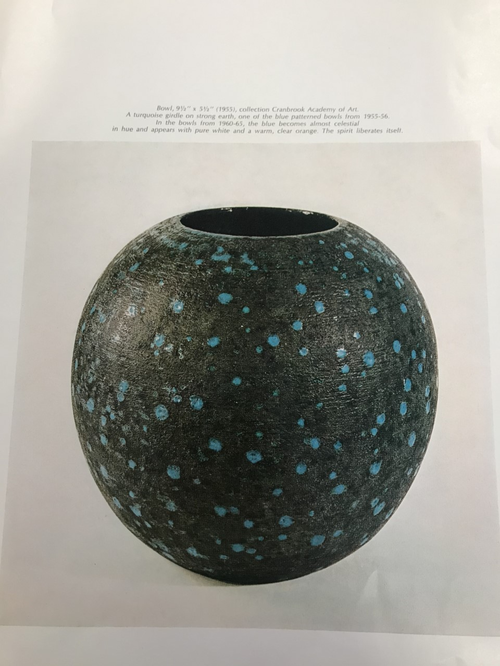

An example of one of Maija Grotell’s works. Maija Grotell Papers.

Black and white photograph of Maija Grotell, holding a large, round vase, 1941. Maija Grotell Papers.

Grotell was a woman working in a male-dominated field who succeeded and prospered in spite of the obstacles she faced. Although women were involved in the pottery movement in the 1900s, few female potters actively practiced their craft between World War I and World War II. Grotell’s ceramics were different than the types of ceramics, glazes, and pottery techniques that came before her in that she used the wheel-throwing technique rather than molding her pieces by hand. Ceramics have long been considered a decorative art and were rarely ever just utilitarian objects. During the early twentieth century, an increasingly affluent society was more apt to purchase ceramics for display in their homes. There was a convergence of fine art and decorative art pieces at this time which contributed to an outgrowth of “fancier” and more intricate wares. Simplistic vessels now incorporated intricate and colorful designs. Grotell differed from these trends in her complex pieces with excited, textured surfaces to create a “wow” factor. She highlighted the beauty and power of the material rather than hiding her pieces beneath overwhelming decoration. In SCRC, there are multiple catalogs of her works, including an image of a well-known piece: her 1955 Bowl, a black bowl with turquoise spots that appears celestial due to its bumpy, opaque glazes. The 1949 issue of Ceramic Age includes multiple examples of Grotell’s works that are useful in identifying the different techniques she incorporated.

Grotell studied painting, sculpture, and design at Helsingfors’ Central School of Industrial Art Athenaeum in Finland, where she graduated in 1920. She joined a textile firm as an artist while continuing her study of pottery. Grotell moved to the United States in 1927 to work and study at Alfred University in New York State. She began teaching ceramics and moved to New York City with many opportunities waiting for her because of her acclaimed status. Determined and motivated as a young artist, she joined the crafts program at the Henry Street Settlement House in New York and found a teaching position at Rutgers University. For most of her career, from 1938 to 1966, Grotell was the head of the ceramics department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. During this period, the height of her career, she assisted in the development of ceramics as a medium of artistic expression. In the 1930s, Grotell’s surface patterns moved toward textured surfaces with linear accents that continued in the 1940s. Her surfaces were rhythmic and dynamic, allowing for new patterns to emerge from her techniques. According to the Cranbrook Art Museum, “Grotell’s experiments would lead her to combine the same Albany slip with a Bristol glaze to create vessels with a pocked surface in which dark and light areas bubbled together like lava. Maija developed a style built on layering glazes one atop another, much like a pearl is formed with layer upon layer of nacre. It wasn’t functional pottery or ceramic sculpture, but a new kind of fine art pottery.” It is these glazes that create unique forms and patterns for which Grotell is known.

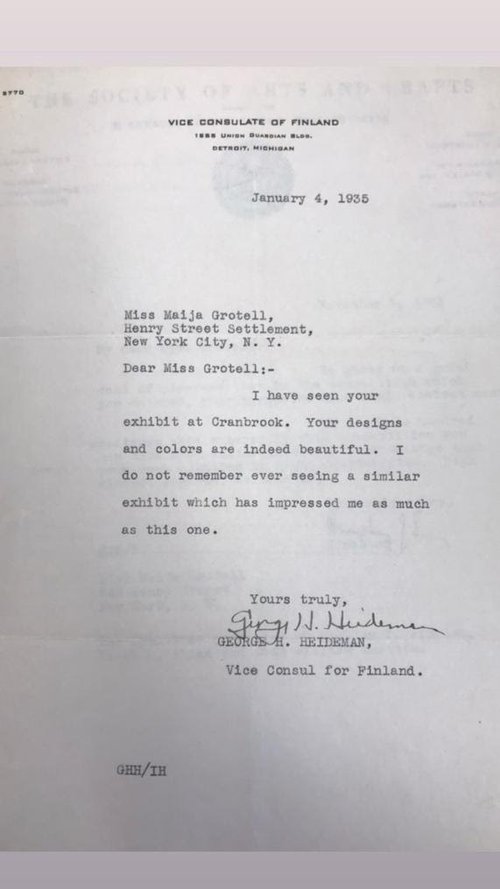

Letter from the Vice Consulate of Finland explaining his admiration for Grotell’s designs. Maija Grotell Papers.

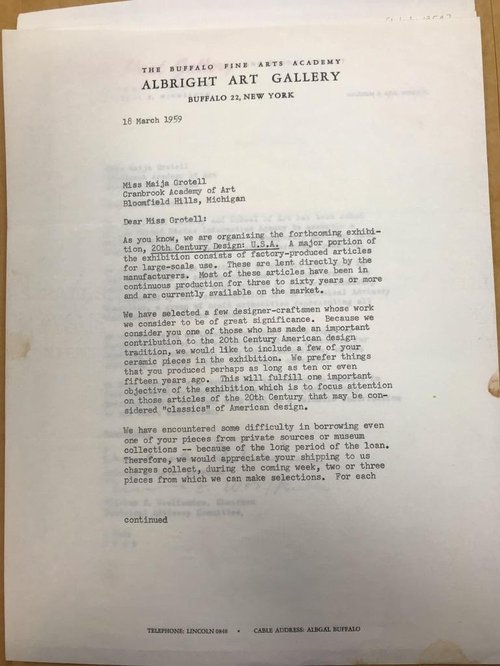

Letter from the Albright Art Gallery wanting to borrow works by Grotell for an exhibition. Maija Grotell Papers.

Grotell’s research into the composition of glazes also made possible the widespread use of colored glazed bricks, helping the ceramics field cross over into other disciplines. Grotell conducted this research for architect Eliel Saarinen and one of her glaze formulas was soon put in use. Saarinen used the formula at his General Motors Technical Center, opening the door to using colored bricks in mid-twentieth century architecture. Because of this innovation, Grotell has been considered a revolutionary in the American design tradition of the twentieth century. In the 1950s, Grotell worked with merging the two techniques of multiple colored slip layers and the next generation of ‘bubbled glaze’ surfaces. She was able to create a highly textured surface by cutting through the surface glaze to the colored contrasting slips beneath. Her glaze formulas remain part of her legacy, and were highly sought after. In a letter from The Albright Art Gallery in 1959, the director praises Grotell for her contribution to American design. In many letters, directors, friends, colleagues, and teachers comment on her exciting pieces. George Heideman states that he had never seen “a similar exhibition which has impressed me as much as this one” in regards to her first exhibition at Cranbrook. Grotell was humble and giving with her work: donating her pieces, making commissions for friends and family, and teaching her craft to children and adults. Her charismatic personality opened many doors for her career, and it was exciting to learn of her generosity, especially considering that she was one of the top female ceramists in the world in her time.

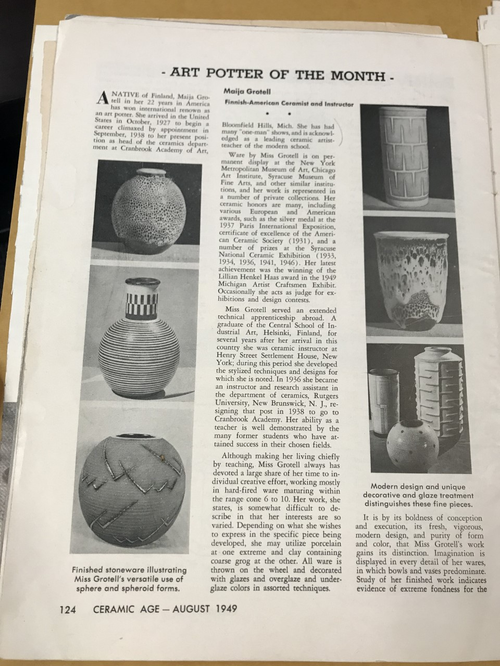

Grotell was one of the European emigrant potters responsible for popularizing the use of the potter’s wheel in America. Grotell took her understanding of the clay body and experimented and transformed it into something new. In America during the early twentieth century, wheel-thrown ceramics were not popular or common; many artists used coiling or slip casting methods. Grotell, along with other European immigrants such as Merguerite Wildehain and Gertrude and Otto Natzler, brought wheel-throwing techniques to America, generating a new trend in American ceramics. Grotell was an expert at wheel-throwing, and was asked to demonstrate her techniques throughout New York City often. Grotell realized that there were endless possibilities with clay and glazes and she took them to the next level. According to an undated clipping from the Art Institute of Chicago, Grotell’s “pottery does not strive for delicacy, but rather for basic simplicity of form and wright adapted to the glaze used.” This endearing quote about her work explains how much the glazes affected her pieces, rather than the clay forms affecting the glazes she chose and used. According to the August 1949 edition of Ceramic Age magazine, Grotell felt that her work “is somewhat difficult to describe in that her interests are so varied. Depending on what she wishes to express in the specific piece being developed, she may utilize porcelain at one extreme and clay containing coarse grog at the other.” According to Jeff Schlanger, a student of Maija Grotell, in an untitled catalogue, “she showed that the modern potter was an artist using an immensely rich language in an era when ceramics was taught exclusively as a hobby craft or a division of industrial design.” There is a particular humanness about her work because her personality is brought out in her pieces in a time when there was an encroachment of industrialization onto the ceramics scene.

Examples of Maija Grotell’s works featured on a page of the August 1949 Ceramic Age magazine. Rare books.

Through the Maija Grotell Papers at SCRC, we can learn a great deal of information about Grotell’s revolutionary career working in ceramics. From primary source material like her correspondence, we can see how desired her pieces were, and how inspiring she was as one of the few female ceramists actively changing the field. My fascination with Grotell’s craft has grown and it is easy to see how her delightful personality and reformed pieces charmed the world. Because her glazes were adopted in other disciplines, her life and works can be studied through many facets. Her impact on the art world is distinct and permanent, even as the fields of ceramics and architecture continue to evolve and change.

The Maija Grotell Papers (Maija Grotell Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of SCRC’s manuscript collections.

Sources:

“Collection Inventory.” Maija Grotell Papers An Inventory of Her Papers at Syracuse University. Accessed January 21, 2021. library.syr.edu/digital/guides/g/grotell_m.htm.

Grotell, Maija. “Vessel.” The Art Institute of Chicago, Arts of the Americas, 1 Jan. 1970. Accessed February 3, 2021. www.artic.edu/artworks/20978/vessel.

Koplos, Janet, and Bruce Metcalf. Makers: a History of American Studio Craft, 159-160. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“Maija Grotell Papers, 1923-1973.” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed February 12, 2021. www.aaa.si.edu/collections/maija-grotell-papers-9673.

“Maija Grotell – Vase – 1940-42.” Cranbrook Art Museum, 31 Aug. 2016. Accessed January 21, 2020. cranbrookartmuseum.org/artwork/maija-grotell-vase/.

“Maija Grotell.” Grotell | The Marks Project. Accessed January 21, 2020. www.themarksproject.org/marks/grotell.

“Maija Grotell – Vase – 1940-42.” Cranbrook Art Museum, 31 Aug. 2016. Accessed February 16, 2021. cranbrookartmuseum.org/artwork/maija-grotell-vase/.

“Maija Grotell.” The Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artists/34754/maija-grotell. “Maija Grotell.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Jan. 2021. Accessed March 4, 2021. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maija_Grotell.