Music in the Stacks

By Nora Ramsey, Reference Assistant

As a musician, I look for music wherever I am. I certainly did not expect to find a manuscript by one of the world’s most famous composers in SCRC’s special collections. When I first found the Franz Liszt Manuscript, I was most interested in contextualizing the music with Liszt’s life and where this piece fits in with the rest of his works.

As soon as I pulled the manuscript from the stacks, I immediately set out to find a recording of the piece. Astonishingly, I had a difficult time finding any reference to it during my first search. There was no record of the piece in any scholarly compilation of Liszt’s works, nor any reference to the piece in any biographies on the composer. After spending too long searching for an easily accessible recording, I asked my friend to sight-read through the music and I was finally able to listen to the piece. From that point on— I was dedicated to learning more about the piece.

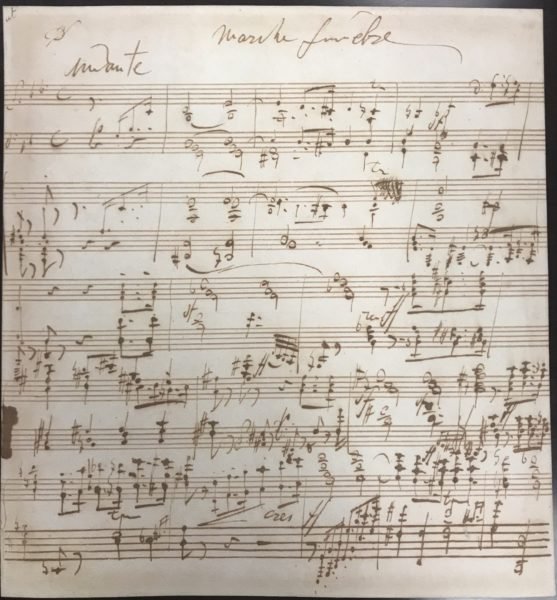

The first page of Franz Liszt's Marche Funebre.

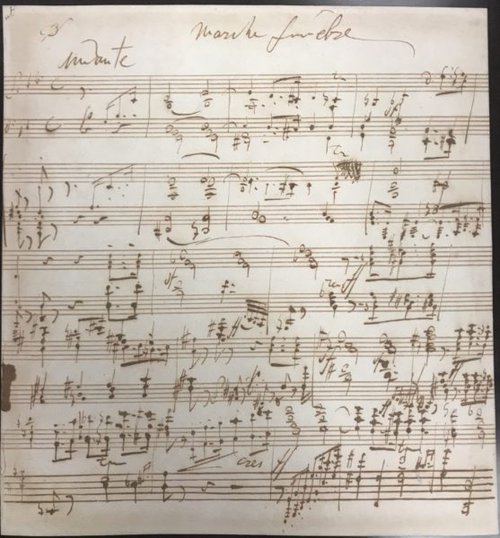

The second page of Liszt's Marche Funebre.

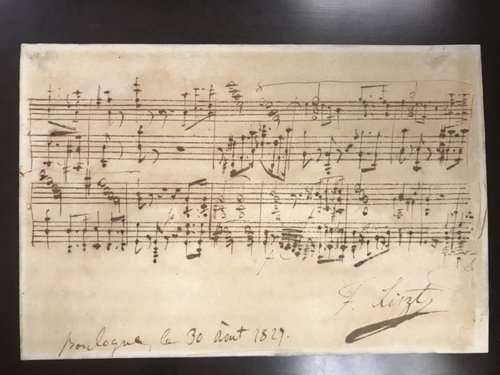

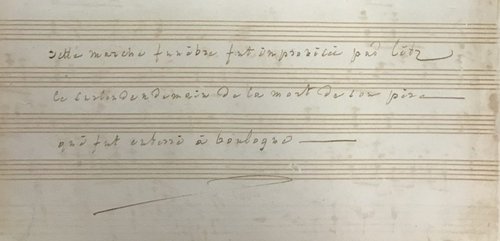

The manuscript consists of two separate paper leaves in different sizes. Each leaf has music inscribed on one side only. The first and larger page consists of five musical systems, or lines of music, while the other smaller one contains only two. The title, Marche Funebre, is written at the top of the page. On the second and smaller leaf, Franz Liszt has signed and dated the bottom of the page. The back of the first leaf has an inscription written in handwriting vastly different from Liszt’s writing on the other side. The inscription in French reads “Cette marche funebre fur improvisee par Litz [sic] le surlendemain de la mort de son pere qui fut enterre a Boulougne.” In English, the writing reads “This march was improvised by Litz [sic] two days after the death of his father who was buried at Boulogne.” The piece is accompanied by a letter from Sotheby's, attesting to its authenticity.

Unsurprisingly, it was Adam Liszt who first introduced his son to music, emphasizing sight-reading, memorization, and improvisation. Adam Liszt cultivated and nurtured his son’s musical talent by taking him on a “Grand Tour” of Europe to display his virtuosity. Thanks to his father, Franz Liszt was one of the most celebrated pianists in Europe by his mid-twenties.

Liszt’s father, Adam, was born on December 16th, 1776, in what is now Slovakia. While not a virtuoso like his son, Adam Liszt worked as a clerk on the estate of the noble Esterhazy family. The Esterhazy family is mostly recognized as the employer of the famous Franz Joseph Haydn. Although Haydn died two years before Franz Liszt was born, Adam Liszt boasted about playing cello in the Esterhazy orchestra under the baton of Haydn himself. Interestingly, Adam Liszt also performed in the Eisenstadt orchestra under Beethoven in 1807. There is no doubt that music played a large role in his life.

In mid-August of 1827, while recuperating with his son from their intense international tour, Adam Liszt fell victim to typhoid fever. On the morning of August 28th, 1827 Adam Liszt died at 50 years old in Boulogne-sur-mer, delivering a crushing blow to his 15-year-old son. This would be the first of Franz Liszt’s many losses. His son, Daniel, would die at the age of 20 in 1859 and his daughter, Blandine, would follow at the age of 27 in 1862. His mother, Anna Lager, would pass only four years later in 1866. After each loss, his natural reaction was to compose memorial music. Les Morts for orchestra and male chorus was composed for his son Daniel; ever-beautiful La Notte for orchestra was composed for Blandine; and the Requiem for two male voices, organ, brass and timpani was finished two years after his mother’s death to commemorate all of his lost family members.

The inscription in French reads “Cette marche funebre fur improvisee par Litz [sic] le surlendemain de la mort de son pere qui fut enterre a Boulougne.”

Prior to Adam's death, Franz Liszt and his father had been inseparable. Liszt's father was often responsible for every minute detail of his schedule from the beginning of their tour. Liszt’s improvisation, Marche Funebre, is likely the first piece to begin the trend of composing memorial music for those close to him. Franz Liszt’s grief over his father’s death and his overwhelming new responsibilities caused a spiritual crisis within the composer. While the pair had a close relationship, Liszt’s diary from 1827 also indicates the tension he felt between his father’s ambition and his own need to make choices for himself. He withdrew from most public performances and stopped corresponding with his friends and family members for close to 3 years after his father's death. Researchers have little information about his activities from this time.

Liszt’s composition, Marche Funebre, has never officially been published and, until recently, had never been cataloged among his works. Until its arrival at Syracuse University’s Special Collections Research Center, the manuscript had remained in private hands with no effort to display or publish the work. The manuscript’s journey can likely never be fully re-traced. Before Sotheby's sale of the manuscript in 1986, the piece was listed in the Maggs Brothers auction catalog in 1921. For a time, the manuscript also belonged to the founder of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, William Andrews Clark Jr.. Clark bequeathed the manuscript to the orchestra's concertmaster, Sylvain Noack, after his death. The manuscript remained in undisclosed ownership in California from this point until it reappeared at Sotheby's.

At first listen, Franz Lizst’s Marche Funebre is not as dramatic as other, more recognizable memorial compositions, like Frederick Chopin’s famous Funeral March. However, the complexity of chords and major tones in Liszt’s work create a more subtle and intimate piece of music. The battle between major and minor chords are an source of extreme tension and confusion not only for the listener, but the performer as well.

With the history of the piece in mind, we invite you to take some time to listen to one of Franz Liszt’s most intimate works, performed by Robert DiPasquale.

The Franz Liszt Manuscript (Franz Liszt Manuscript, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) is part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Works Cited

Liszt, Franz. Marche Funebre. 1827. Andrei Anghel, 2019. Digital.

Nugent, George. “The Heroic Idiom in Early Works of Liszt.” Liszt Saeculum, 1993, pp. 46–60.

Quinn, Erika. Franz Liszt : A Story of Central European Subjectivity. Brill, 2014. (37).