My Year with Tolley

By Dane Flansburgh, Assistant Archivist

For the last few years, the Syracuse University Archives has been steadily at work preparing some exciting exhibitions and programs to celebrate Syracuse University’s sesquicentennial. In conjunction with celebrating this monumental milestone, I have been busy processing collections that have significance to the University. The first and most significant of these collections were the Chancellor William P. Tolley Records and William P. Tolley Papers.

Chancellor Tolley served as Syracuse University Chancellor from 1942 to 1969, beginning in the midst of World War II and ending during the Vietnam War and amid the rise of counter culture. Beginning in January 2018, and ending 12 months later in January 2019, I delved into the life and work of arguably one of our finest Chancellors.

Me (Dane Flansburgh) standing with the unprocessed Tolley boxes in January 2018.

Chancellor Tolley reviewing documents in the 1940s.

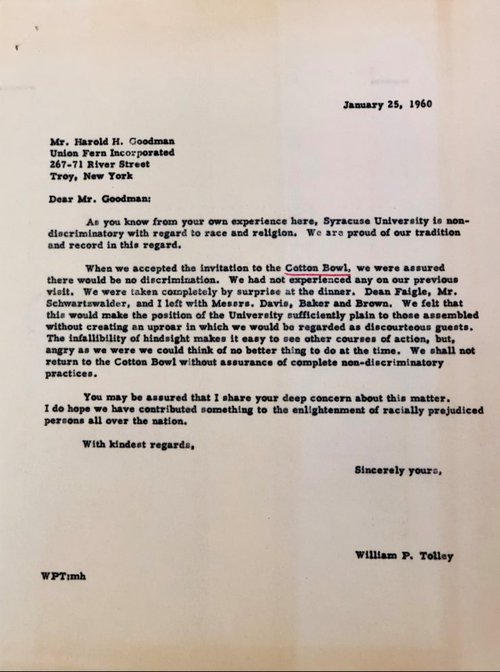

Chancellor Tolley’s January 25, 1960 letter addressed to Mr. Harold H. Goodman regarding the events of the Cotton Bowl.

When Tolley took over as Chancellor of the University in 1942, the country was in the midst of World War II, and Syracuse University was suffering declining enrollments. Upon taking leadership, Tolley went about establishing a university that met the needs of its student body. In a message to students in 1943, Tolley wrote, “While the war has reduced [Syracuse University’s] enrollment, it has greatly increased our responsibilities.” These responsibilities included preparing young people for war and his administration established war training courses and a Nursing School.

Additionally, Tolley assisted drafting the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, or GI Bill, and welcomed thousands of returning veterans at war’s end. Syracuse University continues its commitment to educating veterans based on Tolley’s example. The influx of veterans after World War II spurred exponential growth for the university, and by the time Tolley retired in 1969, his administration had transformed the university from a small private institution into one of the largest universities in the nation.

As I worked through Tolley’s papers and records I developed a deep admiration and respect for him (my coworkers will attest to this – I’d often talk endlessly of the great accomplishments of Tolley and my latest discovery from his materials). There’s a lot to admire about Tolley: his indefatigable work ethic, sincere passion for learning, and unrelenting pursuit of excellence. He cared deeply about Syracuse University, and it showed. He was at times accused of being a micromanager, but he believed that the little details mattered (he once complained in one of his letters to custodial staff that he witnessed too many instances of litter in one of the buildings, and he was uncomfortable with the sloppy appearance that it gave). He had close relationships with many members of the Syracuse University community, including students, staff members, professors, and donors. One student remembered that when she informally stopped in his office to invite him to a sorority event, she was astounded when he welcomed her warmly, and then surprised her by actually attending the event.

But more than any other of Tolley’s fine accomplishments and character traits, I was personally drawn to his commitment to fairness and equity. One of the more treasured items I discovered in Tolley’s papers was a letter from Warren Tsuneishi ‘43. Tsuneishi was a Japanese American student who attended Syracuse University during World War II. In 1943, Tolley quietly admitted to Syracuse University roughly one hundred Japanese Americans from internment camps, including Tsuneishi. The move, at the time, was seen by some as aiding the enemy, but Tolley rightfully argued that the people in the camps were in fact Americans, despite their country of origin.

In the letter, dated July 4, 1983, Tsuneishi wrote, "Your act of moral courage in the face of opposition immeasurably strengthened my own belief and confidence in American democracy. I knew then that despite temporary setbacks under extreme provocation in wartime, the champions of constitutional rights, equity, and fair play for all Americans would in the end prevail." Tsuneishi stated that he took advantage of the opportunity granted to him by enrolling in an accelerated program at Syracuse University, serving in the United States Army, attending graduate school at Columbia and Yale, and then serving as a librarian at Yale and the Library of Congress. “I recount these accomplishments,” Tsuneishi wrote, “not to boast but to observe that none of these could have been accomplished had you not given me that first chance in 1943.”

I’d like to highlight one more story that emphasizes Tolley's commitment to equality. In January 1960, the Syracuse University football team defeated the University of Texas at the Cotton Bowl and won the national championship. Days after the event, there were reports that the African American members of the team (including the great Ernie Davis) were subjected to racial slurs and discrimination. The accusations of discrimination included banning the African American players from attending the awards ceremony that immediately followed the game.

The Chancellor’s office received several angry letters about the perceived slight. Responding to a concerned Syracuse University alumnus, Tolley clarified that when the African American team members were asked to leave, Coach Schwartzwalder, Dean Faigle, and himself left out of protest. In hindsight, Tolley wrote, he wished he went even further and had all of the team leave as well. In the future, Tolley promised, the team would not “return to the Cotton Bowl without assurance of complete non-discriminatory practices.” This instance, like Tolley’s reaction to the Japanese American students during World War II, demonstrates his character.

I sincerely valued my year processing Tolley’s records. He inspired me to work harder and to be more empathetic. I invite the public to visit the Special Collections Research Center to learn more about his life and achievements.

The photos in this post are part of our Chancellor William P. Tolley Records (Chancellor William P. Tolley Records, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and our William P. Tolley Papers (William P. Tolley Papers, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries).