Tempering Virtue, Prohibiting Vice

by Grace Wagner, Reading Room Access Services Supervisor

Prohibition is often seen solely within the context of bootleggers, speakeasies, flappers, and the flagrant flouting of an archaic law set into place by a governing body out of touch with the realities of the populace. When the Volstead Act came into effect on January 17, 1920, it ushered in a 13-year period where alcohol’s production, sale, and distribution was prohibited by constitutional law.

Socially, economically, and politically, this move impacted the American people as a whole. From reform leaders to satirists and political cartoonists, from pious industry titans to the various political factions seeking government office, opinions ran the gamut, from those strongly in support of the movement to those who regarded the entire decision as little more than a joke. The strong feelings evoked during this period demonstrate how temperance was an issue that had far more nuance and longevity to it than is always granted in our reimagining of the past. SCRC’s collections help us to make sense of various viewpoints during this movement, from the 19th century into the present day.

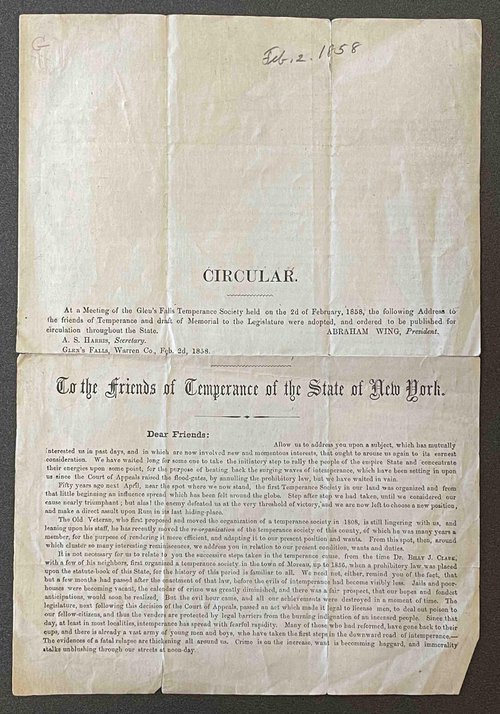

“Dealing out poison” [1858]

Gerrit Smith pamphlet, “To the Friends of Temperance of the State of New York”, dated 1858, which advocates for a new state amendment. Gerrit Smith Pamphlets and Broadsides, Rare books.

Although the Volstead Act was not passed until 1920, the temperance movement had its roots much earlier in American history. Alongside abolitionism and suffrage, temperance ranked high among the social issues most important to reformers of the 19th century. Gerrit Smith, a known abolitionist and suffragist who lived in upstate New York and corresponded with Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony, among others, was also a supporter of the temperance movement. Smith’s views on the subject can be seen in the “To the friends of temperance of the state of New York” pamphlet that Smith addressed to the Glens Falls Temperance Society on February 2, 1858:

“But the evil hour came, and all our achievements were destroyed in a moment of time The legislature, next following this decision of the Court of Appeals, passed an act which made it legal to license men, to deal out poison to our fellow-citizens, and thus the vendors are protected by legal barriers from the burning indignation of an incensed people… The evidences of a fatal relapse are thickening all around us. Crime is on the increase, want is becoming haggard, and immorality stalks unblushing through our streets at noon-day.”

Gerrit Smith, “To the friends of temperance of the state of New York”

Smith was not alone in his beliefs. Temperance was also a major political issue for many women and suffragists at the time, who knew firsthand the impact unregulated liquor production could have on their home lives.

In the pamphlet, Smith calls upon the need to “incorporate the principle of prohibition into the organic law of the State,” but simultaneously acknowledges that “there has been no concentration of effort — no harmony of views, or definite purpose of action,” in reference to the efforts made on behalf of the movement itself. This observation serves as a harbinger for the way in which the temperance movement seemed to lurch along through the years, never ceasing to exist entirely, but slowing losing the initial drive and purpose that once held it together.

“I hate reformers” [1922]

The cover for the 1922 volume, Nonsenseorship. Rare books.

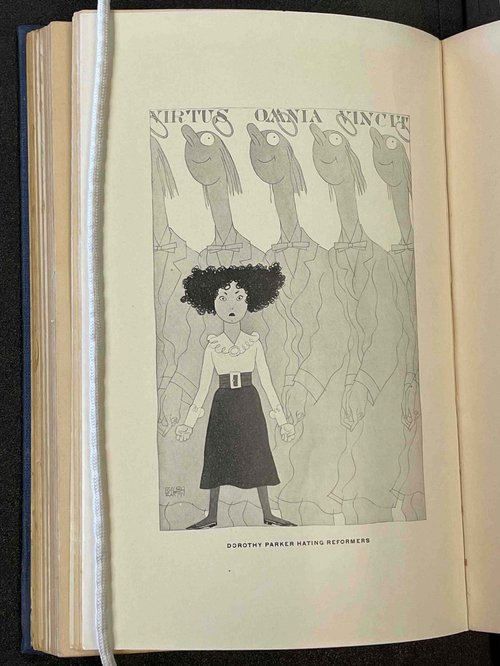

Dorothy Parker Hating Reformers from Nonsenseorship, illustration by Ralph Barton. Rare books.

Soon after Prohibition was set in place, the anthology, Nonsenseorship: observations concerning prohibitions, inhibitions and illegalities, was published. The volume was a collection of the thoughts of “a group of not-too-serious thinkers” on issues of alcohol regulation and other government reforms. Dorothy Parker and Ben Hecht were among the thinkers pegged to write for the anthology that was illustrated by Ralph Barton.

Not one to mince words, Dorothy Parker’s “Hymn of Hate” spared no enemy the ire of her pen. From prohibitionists, to movie censors, to those who exhibited moral outrage at cigarette smoke or shortened hemlines, Parker managed to reject the various groups concisely with only a few words at the top of her hymn: “I hate reformers; they raise my blood pressure.” Dorothy Parker’s take on Prohibitionists expressed similar sentiments: “They [Prohibitionists] can prove that the Johnstown flood, / And the blizzard of 1888, / And the destruction of Pompeii / Were all due to alcohol.”

“Is It Right?” [1926]

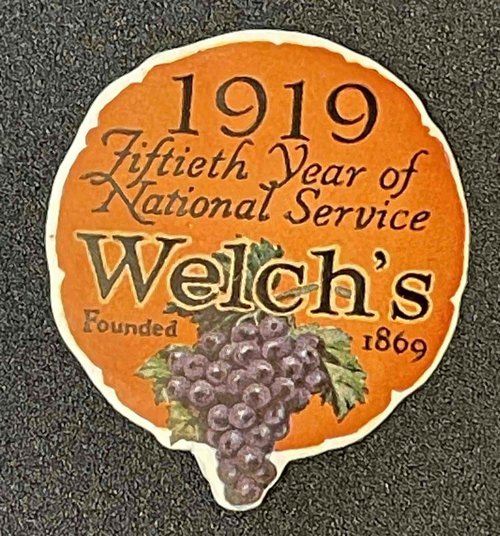

A badge celebrating fifty years of Welch’s from 1919, shortly before Prohibition and bootleggers temporarily caused the business to experience a loss of profits. Edgar T. Welch Papers.

![“Is it Right?” [1944] from the New York State Issue, a Anti-Saloon League publication, saved by Welch. Edgar T. Welch Papers.](/media/images/Is_it_Right_1944_from_the_New_York_State_Issue.width-500.jpg)

“Is it Right?” [1944] from the New York State Issue, a Anti-Saloon League publication, saved by Welch. Edgar T. Welch Papers.

It is unlikely that Dorothy Parker and Edgar T. Welch, the son of the founder of Welch’s Grape Juice company, would have found any commonality in their beliefs. In 1869, Dr. Welch, a dentist, began producing unfermented wine for church services and medicinal purposes. By 1893, the company had changed their name to Dr. Welch’s Grape Juice and switched entirely over to manufacturing juice products. Despite the fact that the company never produced alcoholic products, the wine and liquor industry still had an impact on Welch’s business. In fact, in a history of the company, Prohibition is cited as having a “disastrous,” but temporary, impact on the grape juice industry, as buyers seeking grapes “for illicit use” caused the price on Concords to rise to astronomical levels and grape juice manufacturers to operate in the red for the next two years.

It is perhaps not surprising that Edgar T. Welch, who took over his father’s business in 1926, continued to ruminate on this subject and saved a 1944 clipping from the Official Organ of the Anti-Saloon League of New York, titled, “Is It Right?”, that posited, among other moral quandaries: “Is It Right for the Government to require ration points for Grape Juice, but none for Grape Wine? Both are made from Grapes and Sugar.” Welch later resigned from his business position to work for and spread the word of the Methodist Church. Edgar T. Welch's papers are held at SCRC.

“Getting sick of the voyage” [1926]

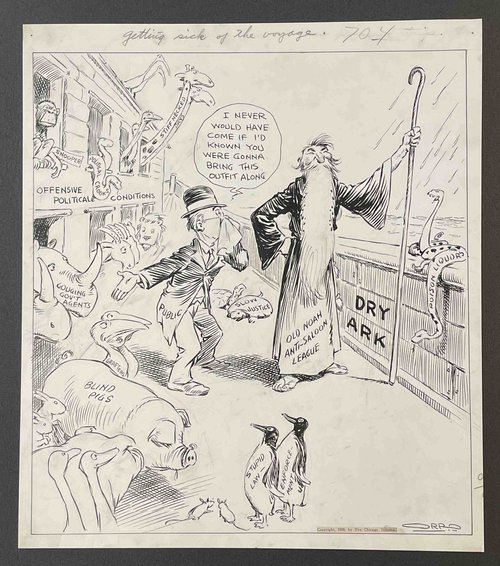

Carey Orr’s cartoon of Noah’s ark, demonstrating how the American populace was beginning to “Get Sick of the Voyage.” Carey Orr Cartoons.

A Moon Mullins cartoon featuring Moon’s younger brother Kayo, depositing what appears to be bottles of alcohol out the bedroom window. Frank Willard Cartoons.

By 1926, Prohibition restrictions had been in place for six years, and many were ready for the experiment to be over. Among them was Chicago Tribune contributor Carey Orr, a political cartoonist who frequently incorporated the prohibition question into his cartoons of this decade.

One such example was a cartoon from 1926 titled “Getting sick of the voyage,” with a depiction of Noah’s ark and various animals gathered on board. In this case, however, the ark is a “Dry Ark” and Noah is the “Anti-Saloon League.” Various animals onboard include, “Stupid Law Enforcement,” “Stiff necked drys,” “Political Crooks,” and “Gouging gov’t agents’,” among others. On board is a man labeled “Public” who says to Noah, “I never would have come if I’d known you were gonna bring this outfit along.”

Another cartoonist who found his footing during the era of Prohibition was Frank Willard, whose comic strip Moon Mullins debuted on June 19, 1923. The nickname of the title character, “Moon,” was short for “Moonshine,” a term that had deep roots in American history, but gained additional traction during the Prohibition era. Willard drew Moon Mullins until his death in 1958, and the cartoon continued to have a life beyond this point in time, until it ceased its run in 1991. Even in later cartoons, allusions to alcohol continued to be depicted and pop up in unlikely places in the cartoon. The above cartoon from 1944 shows Moon’s younger brother, Kayo, another regular character who appeared in the comic strip, gathering up an assortment of heavy objects, including what appear to be several bottles of liquor — perhaps moonshine — to throw out the window.

“Will beer bring back prosperity?” [1932]

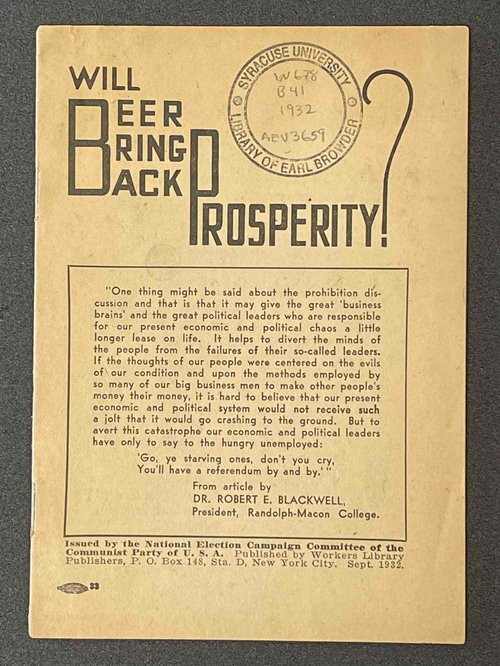

“Will Beer Bring Back Prosperity?” was a booklet published by the Communist Party in 1932. Rare books.

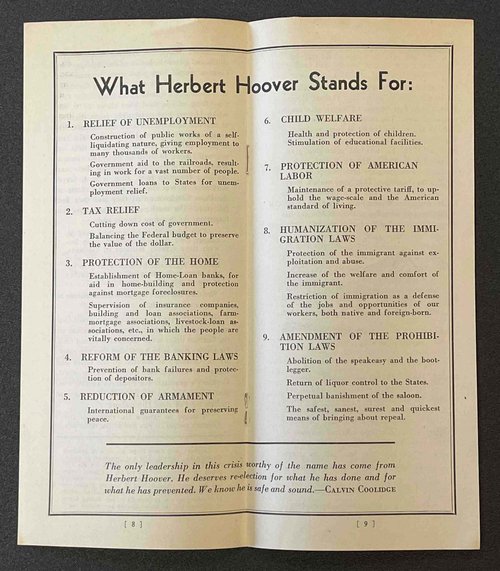

Herbert Hoover’s 1932 platform included “Amendment of the Prohibition Laws,” demonstrating how Republicans and Democrats had become united on this issue by this time. Campaign Collection.

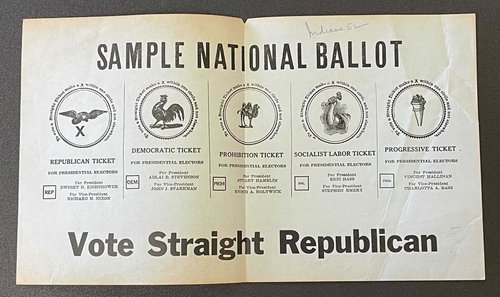

A national ballet from Indiana in 1952, where the dry camel representing the Prohibition Party, remains on the ticket. Campaign Collection.

The repeal of Prohibition was a key issue on the 1932 election ticket, not only because people were decidedly “sick of the voyage,” but also because the economic state of the country had left many citizens in a state of turmoil. Democrats and Republicans alike were now in favor of repealing the Volstead Act, though their approaches to this differed by degrees of severity. The Communist Party published the 16-page pamphlet “Will beer bring back prosperity?” that year, making their position clear (repeal), while simultaneously citing the capriciousness of their opposing parties: “Both Republicans and Democrats advocated prohibition; now they both advocate its repeal. In 1920, they promised ‘prosperity’ through prohibition; now they promise ‘prosperity’ by the repeal of prohibition.”

Of the ticketed parties, it was only the Prohibition Party that sought to keep the restrictions in place past 1932. And, although the Volstead Act was repealed in 1933, led by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had ultimately won the 1932 election on the Democratic ticket, the Prohibition Party did not disband shortly thereafter, or indeed, even at all. In the 1950s and beyond, even today, the party continues on, still looking at temperance as a model to uphold, but diversifying the party platform with other issues of concern, including states rights, law reform, and lowering government spending and taxes.

The Campaign Collection (Campaign Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), the Edgar T. Welch Papers (Edgar T. Welch Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), the Carey Orr Cartoons (Carey Orr Cartoons, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), and the Frank Willard Cartoons (Frank Willard Cartoons, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of SCRC’s manuscript collections. “Nonsenseorship,” “Will Bring Bring Back Prosperity?,” and the Gerrit Smith Pamphlets and Broadsides are part of SCRC’s rare books collection.