World War II Veterans at Syracuse University

by Meg Mason, University Archivist

This week, we honor our veterans and their service. Veterans have long been a significant part of Syracuse University history. Most notably, the University Archives holds documentation of the dramatic influx of veterans on campus right after World War II. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill, offered millions of veterans a college education, something most would not have been able to otherwise achieve. Syracuse University reached out to veterans, who enrolled in significant numbers immediately after the war, bringing immense change to campus. Within four years following the end of the war, total enrollment at the University more than tripled. SU ranked first in New York State and 17th in the country in veteran enrollment. As a result, the campus immediately needed more housing and classrooms, and temporary buildings sprang up all around campus and surrounding areas. The University Archives not only holds University records that document these transformations, but also holds archival materials about individual veterans who attended SU. Together, they tell the story of SU’s postwar years and reveal where there are still gaps in our collections.

From POW to Undergrad

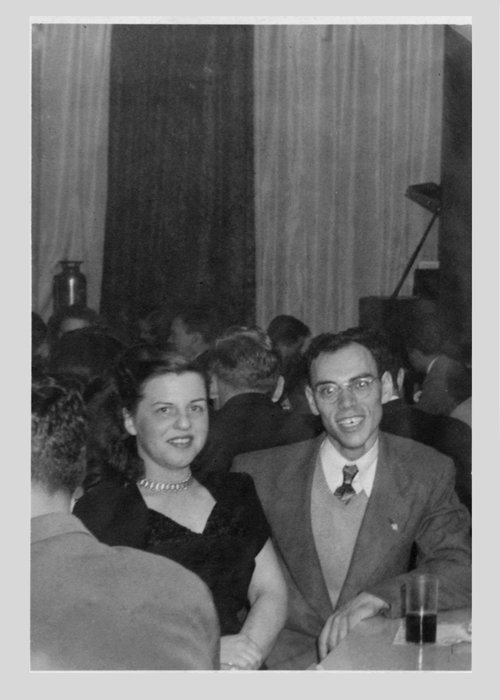

Photograph of Attilio Mascone and Beatrice Jean, circa late 1940s. Attilio Mascone Papers.

Although every veteran enrollment experience was different, Attilio Mascone (1921-2009) serves as a good example of one World War II veteran’s time on campus. Mascone served in the 106th Infantry during the war. In December 1944, within days of arrival in Europe, his unit, the 422nd, was captured by German forces during the Battle of the Bulge. After a forced march in the freezing cold and a grueling trip crammed in boxcars, Mascone and his fellow POWs were held in the overcrowded prison camp Stalag IX-B, near Bad Orb, Germany, one of the most brutal of the German POW camps. American forces liberated the prisoners in the spring of 1945. Back in the United States, Mascone spent some time recuperating. As he later recounted to his daughter, despite being “several pounds lighter, suffering from malnutrition, stomach pain, the residual effects of frostbite, and lack of dental care in the camp,” he entered Syracuse on the GI Bill. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering in 1948.

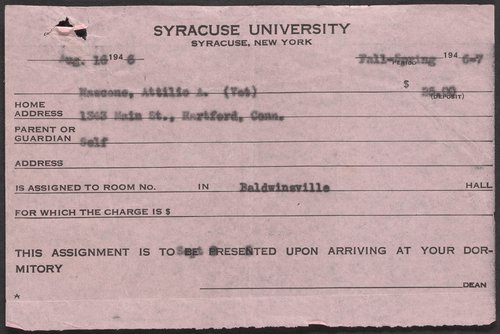

Dormitory assignment slip for Attilio Mascone, August 16, 1946. Attilio Mascone Papers.

Though a very small collection, the Attilio Mascone Papers document much about the veteran student experience at SU. Mascone was older than the average undergrad and lived in various temporary housing instead of regular dorms. Until the new housing was ready for veterans on campus, veterans lived all over the local area, including the New York State Fairgrounds, Baldwinsville Ordinance Works, and the Army Air Base at Mattydale. Mascone was assigned to Baldwinsville in 1946. Other materials document campus life, including visits from Mascone’s future wife, Beatrice Jean, who would come to campus to attend campus events such as dances with him.

Women Veterans

Photograph of Margaret Hastings and Dwight Eisenhower after her return from New Guinea, November 1945. Photograph by ACME. Margaret Hastings Collection.

Attilio Mascone’s experience may have been typical for a male veteran, but what about the women? We can look to Margaret Hastings (1914-1978), who attended Syracuse University in the late 1940s. She joined the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in 1944, becoming a corporal and serving in New Guinea. In May 1945, Hastings was aboard a military transport plane with 23 other service men and women when it crashed into the remote jungles of Papua New Guinea. Injured, she was one of only three survivors, stranded for 47 days until rescue. Hastings’ story turned her into a media sensation in the United States, where reporters dubbed the New Guinea jungle “Shangri-la.” Upon her return to her hometown of Owego, New York, she received a hero’s welcome with a parade. There was even some Daily Orange coverage about her.

Yearbook photo of the Women’s Veterans Association from the 1950 Onondagan. Syracuse University Yearbook Collection.

Hastings wasn’t the only woman veteran to attend Syracuse University or other colleges and universities under the GI Bill. About 35% of the 350,000 women who served in the armed forces during the war took advantage of the bill’s education benefits. Women represented less than 2 percent of those who served, though, and the federal government did not actively encourage them to utilize the GI Bill. There is very little documentation of women veterans after World War II in the University Archives, not even numbers, though they were probably small. They do show up in the yearbooks and the Daily Orange, so we know they were here! There is a tiny Margaret Hastings Collection in the Archives, but it focuses mainly on the New Guinea crash rather than her student experience.

Where are our Black Veterans?

The veterans discussed above were white, and there is more archival material about white male veterans in the University Archives than any other group. Students who were Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) were already in the minority of students on campus, and they have not been well represented in the University Archives. Historical enrollment records did not document students by race, and the presence of BIPOC veterans is difficult to trace as well. However, I was able to find one file that confirmed that, as early as September 1946, at least a few Black veterans were here after the war.

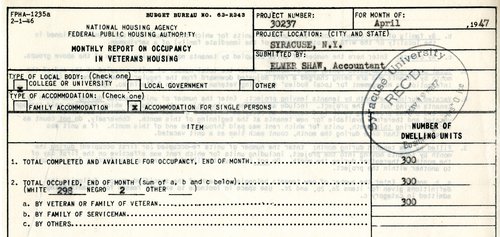

A file from the Syracuse University Treasurer’s Office Records contains reports that the University was required to submit to the federal government to account for its use of temporary housing purchased from the U.S. War Department. These reports required the University to provide demographic occupancy numbers of veterans — including by race. The file isn’t a complete accounting of all veteran housing on campus, and the reports seem to account for varying sets of housing. Black veterans probably lived in other parts on or off campus as well, but the numbers of Black veterans in these occupancy reports are disappointingly low — 1 or 2 at a time — and may reflect their likely low numbers here at SU.

Detail from the monthly report on occupancy in veterans housing submitted by Syracuse University to the National Housing Agency and Federal Public Housing Authority, April 1947. Syracuse University Treasurer’s Office Records.

These low numbers were probably common at other colleges and universities, at least at those who admitted Black students. Black veterans were just as eligible for GI Bill benefits, but the bill presented obstacles, namely systemic racism and an unhelpful Veterans Administration, that prevented many from taking advantage of them. Some Black veterans could not afford to attend college, even with the benefits. Others found that a history of poorly funded public education for Black students did not prepare them for college. Many who applied for admission faced official or unofficial quotas for Black students (In the University Archives there is documentation of efforts of administrators to limit Black student enrollment at SU in the 1920s, but, so far, we haven’t found any such records in the decades following.).

While the GI Bill greatly improved and transformed the lives of white Americans in the postwar years, many Black veterans who had served their country in the war were shut out from those benefits. Even though those occupancy reports hint at measly numbers of Black veterans at Syracuse University, I was heartened to see their presence on campus documented here in the University Archives. I hope BIPOC and women veterans who are SU alumni may consider donating some materials or even information about their attendance here on campus. We need the voices of all our veterans heard and preserved in the University Archives because they are a part of Syracuse University history.

The Attilio Mascone Papers (Attilio Mascone Papers, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), Syracuse University Treasurer’s Office Records (Syracuse University Treasurer’s Office Records, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), Syracuse University Yearbook Collection (Syracuse University Yearbook Collection, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), and the Margaret Hastings Collection (Margaret Hastings Collection, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of our University Archives collections.

Additional Sources:

Herbold, Hilary. “Never a Level Playing Field: Black and the GI Bill.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education no. 6 (Winter 1994-95): 104-108. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2962479

Willenz, June A. “Invisible Veterans: Women Veterans Use of World War II GI Bill.” The Educational Record 75, iss. 4. (Fall 1994): 40.

Johnson, Shane. “Female World War II Veteran Gets Historic Marker in Owego.” WSKG (12 August 2016).Female World War II Veteran gets Historic Marker in Owego.