X-ray Music: The Bone Records of Soviet Russia and the Art of Bootlegging

Page featured image content

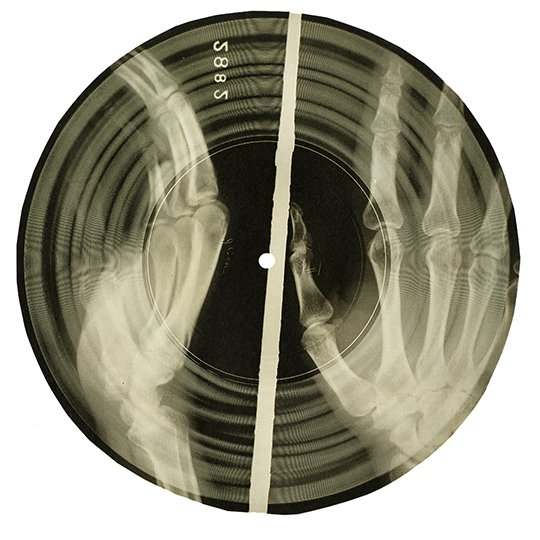

Photo credit: Photographs were taken from the book "Bone Music" by Stephen Coates. ISBN 978-1913689476.

Page main body content

February 4 - February 28, 2025

The culture of pre-communist Russia included a rich and vibrant music scene, but with the rise of socialist realism, the state became progressively involved with even popular culture. By the late 1930s, all forms of art - including architecture, painting, literature, and music - were regulated by censors. State radio, with its steady stream of propaganda and tightly controlled playlists, was the primary source of news and music. Youth were cut off from their own heritage, and the blossoming music styles of the West - including the emerging rock and roll genre - were all but untouchable. To the government, most non-approved music had become the enemy, a corruptor of youth and a toxic element to be cauterized to protect the system.

Into this oppressive environment of postwar Leningrad, bootleg recording pioneers emerged, salvaging discarded technology to circumvent state censorship by creating and disseminating pirated physical media. Due to the odd medium used in their creation, they became known as bone or rib records. Images in the discs include broken ankles, ribs, skulls, and other damaged body parts. For the consumer, there was always an element of risk when it came to recording quality.

The types of music that appeared were taken from pre-existing vinyl records. Either left over from before the revolution or newly imported, source discs were rare and expensive, their spotty availability limiting what could be reproduced. Many records were regional in nature or classical and jazz, but popular among them was the new music from the West. Early bootlegs featured pre-war jazz, tango, and Russian émigré music. As Western music slowly filtered in, bone recordings began to include artists such as Duke Ellington, Bill Haley, and later even Elvis Presley and The Beatles.

Bootleg record dealers and those who made the illegal recordings were imprisoned for years at time. Upon Stalin’s death in 1953, a general amnesty was declared, and over a million prisoners were set free, with some bootleggers returning to recording and spreading the illegal music. The underground movement continued, with various independent groups taking up the cause.

Less than a decade later, the bone record was on the verge of extinction, supplanted by the reel-to-reel audio recorder. Audio tape was cheap, easier to acquire, with superior sound quality and a longer recording time. Most importantly, it was a format deemed legal by censors.

By the mid-1960s, the last of the bone records had been etched.

Materials on display are from a private collection.