COVID Cataloging Project

by Chelsea Hoover, Catalog Librarian of Music

One month after I assumed my role as Music Catalog Librarian for Syracuse University Libraries, I was introduced to my first sound recordings cataloging project, the Bell Brothers Collection of Latin American and Caribbean Recordings. This collection was acquired by Syracuse University in 1963 from the Bell Music Box Record Shop in Manhattan, New York, and the collection consists of approximately 12,000 seven-inch vinyl records that play at speeds of 45 revolutions per minute. My introduction occurred ever so conveniently at around the same time that COVID prompted an abrupt transition to indefinite remote work for all Syracuse University employees.

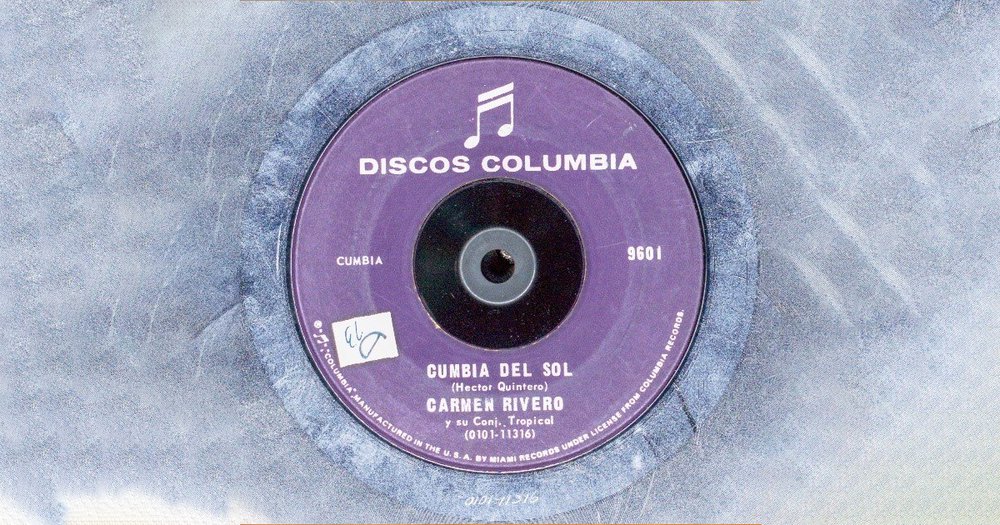

You may be wondering, “If you could not physically catalog these recordings inside the library, how were you able to catalog them remotely? Did you have to bring the recordings home with you?” Surprisingly, I did not have to bring any recordings home with me, as many of them had already been digitized by Belfer Audio recording engineer Jim Meade and other Belfer staff. Mike Dermody, the Digital Preservation and Projects Coordinator at Belfer, created a flash drive he gave me before we were sent home that contained the image and audio files from every digitized recording. Consequently, most of the information I needed to create the catalog records could be found from studying the digitized image and audio files in the flash drive. The screenshot below gives an example of what an image file of one of the digitized discs looked like.

The next question you might be asking is, “What kind of information do you even put in a catalog record of a sound recording?” The short answer is that I aim to include information in a catalog record that will tell patrons exactly what is on the recording and where in the library patrons would be able to find the recording. This descriptive information includes the following elements: the title of the record, the title of each individual track on the recording, the composers of each track, the performers on the recording, physical attributes of the recording (i.e. vinyl, stereophonic, etc.), publication information, music genre form terms, instruments involved on each track, and important numeric identifiers, such as matrix and issue numbers.

As previously mentioned, I was able to determine most of this descriptive information by examining the image files of the digitized records and then transcribing the information into the catalog records exactly as it appeared on the digitized records. The one descriptive element I did not determine by studying the image files, however, was the instruments involved on each track. I determined this element instead by listening to the audio files of each track and recording the names of the instruments I heard, using the Library of Congress Medium of Performance Terms thesaurus as a reference for recording the instruments by their standardized names. For each catalog record I created, I initially input my information in OCLC, the worldwide online catalog database, and then exported the OCLC record to Classic Catalog, Syracuse University Libraries’ online catalog database. Finally, I created a call number, which told patrons browsing Classic Catalog exactly where they would be able to find the record.

For this specific collection of recordings, the call numbers were based off the numeric identifiers of each recording. And in the case of the digitized record from the screenshot above, the call number I created was Discos Columbia 9601, and the record is located in Belfer.

If you are wondering what challenges I encountered as I catalogued these sound recordings, I would say that one challenge has been that not every digitized record has had a digitized image of its corresponding album cover. Oftentimes these album covers have been particularly helpful, as they have explicitly spelled out information that can otherwise be difficult to gage just by looking at the digitized disc label, such as title and performer information. In such cases of an ambiguous disc label with no album cover, I have had to resort to Google search to find information about the disc that I am missing or unsure about, which is often time-consuming.

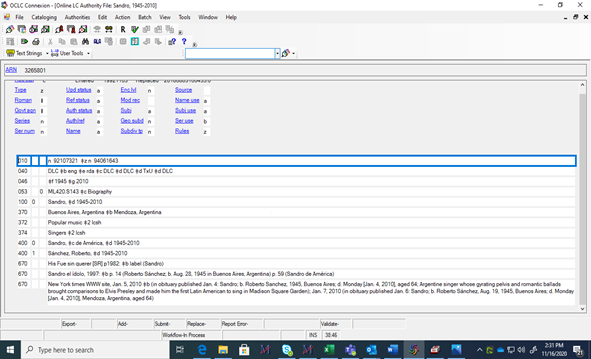

Another challenge has been finding and establishing the correct access points for some of the performers’ names. Access points are crucial in catalog records because they often link to authority records for the performers in OCLC, and the authority records are consequently critical because they establish the standardized form of the performers’ names, as well as any cross-references, and thus provide consistent name usage in OCLC. The screenshot below gives an example of what an authority record looks like and why it is important for establishing consistency in OCLC.

This screenshot shows what an authority record looks like for the Argentinian singer Sandro, a performer I encountered in several Latin American 45 records. The 400 fields in the record are variant names by which Sandro has been recognized. You can probably imagine how much more cluttered the OCLC database would be if these 400 fields did not exist to link the different usages of Sandro’s name into one authority record.

With many performers from the Latin American 45 records, such as Sandro from the above screenshot, I have concluded that the established authority records for the performers in OCLC are variants of the names indicated on the digitized records. But before I reached this conclusion, I had to have unsuccessful searches in OCLC when I attempted to search for the performers by the names indicated on the digitized records. I then had to resort to Google to find any variant names of the performers, and then if the performers do have variant names in Google search results, I had to search all the variant names in OCLC. Therefore, searching for these variant name usages in Google and OCLC authority file has also been extremely time-consuming.

Nevertheless, these challenges have helped make cataloging the Latin American 45 records an interesting and exciting endeavor. And I look forward to seeing how the rest of the sound recordings from this collection will continue to challenge me as a music cataloger.