Bringing Art to the People

By Courtney Asztalos, Plastics and Historical Artifacts Curator and Jana Rosinski, Curatorial Assistant for Plastics and Historical Artifacts

"The political revolution would only be achievable through a demonstrable form of cultural remaking. In other words, culture was the soil on which politics were played out. In this sense, perhaps culture played a more central role in revolutionary imagining than it is given credit for… "

Christopher M. Timson, New Breeds, Old Dreams: Liberator and Black Radical Aesthetics

On February 19th, Syracuse University Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) hosted a special pop-up exhibit on the Black Arts Movement. The Black Arts Movement was an African American-led arts movement that occurred approximately between 1965 and 1975. In the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination, African Americans were redefining their relationship as citizens of the United States. Through the sister movements of Black Arts and Black Power, many institutions of Pan African and African American education were birthed from the labor of the artists and activists who created the works and taught from them. The Black Arts Movement represented Black life amidst, and in reaction to, the vast cultural, political, and social upheaval of the times, through poetry and small press publications, plays, illustrations, artwork, and more. In this post, we will highlight a selection of materials that caught visitors’ attention at the pop-up.

An essential means of bringing art to the people was through music performance. One resource unique to SCRC is an audio recording of musician Gil Scott-Heron’s Live Session at Syracuse University’s Hendricks Chapel on February 8th, 1973. Heron was a poet, musician, and spoken word performer, best known for his famous anthem, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. We discovered this rare recording within SCRC’s WAER Collection, which consists of non-commercial recordings, all off-air dubs on reel-to-reel tapes. WAER is a local Syracuse radio station that was student-run until 1983. Recorded around the time of the release of Scott-Heron’s second studio album, Free Will, the themes of the performance reflect his centering of the Black experience, including respect for natural Black hair, Black pride, and the fight for the visibility of Black culture in white-dominant mainstream culture.

Paramount to the Black Arts Movement was the social activist, poet, playwright, editor, novelist, music critic, and credited founder of BAM, LeRoi Jones, who became known by his adopted name Imamu Amiri Baraka during the 1960s and 1970s. SCRC holds the papers of LeRoi Jones (inclusive dates 1957-1968), a collection that permits researchers a unique perspective into the early years of BAM. One selection from Baraka's papers included in the pop-up was Baraka’s take on "The Task of the Negro Writer As Artist," published in a 1965 issue of Negro Digest. The importance of Negro Digest to BAM was crucial as it was the only journal of the movement that could be purchased at major newsstands. In this largely circulated essay, Baraka speaks to the necessity of centering the Black experience within Black consciousness:

"The Black Artist must draw out of his soul the correct image of the world. He must use this image to band his brothers and sisters together in common understanding of the nature of the world (and the nature of America) and the nature of the human soul."

LeRoi Jones (Imamu Amiri Baraka)

Baraka’s writing is an early example of the emergence of BAM’s new Black consciousness and his essay sits among a range of intergenerational dialogues and perspectives in this issue.

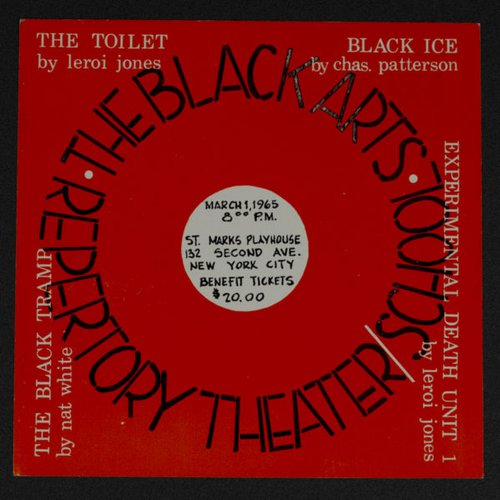

Front and back of the BARTS benefit handbill.

This handbill advertises four plays by LeRoi Jones, Chas. Patterson, and Nat White–for a benefit on March 1, 1965, at St. Marks Playhouse.

Baraka was also foundational part of the opening of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre and School (BARTS) in Harlem, authoring plays alone and collaborating with other artists like Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, and Sonia Sanchez. Black theater was expanding in new directions motivated by the imperative to bring the full depth of the Black experience to Black audiences. BARTS inspired many other Black theaters and performances, like this spoken word performance by the Young Spirit House Movers.

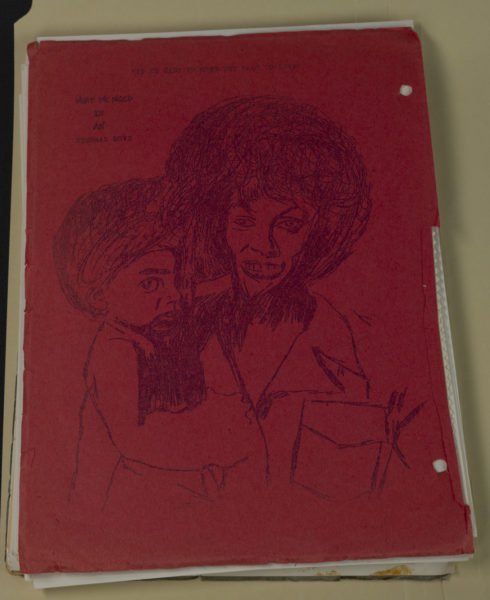

In The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones, Baraka writes, “Bringing art to the people, black art to black people, and getting paid for doing it was sweet. Both the artists and the people were raised by that experience.” One specific example is found within SCRC’s Grove Press Records. It is no surprise that this handmade manuscript of Black student voices growing up in the Movement was submitted to Grove Press, known for its progressive publications.

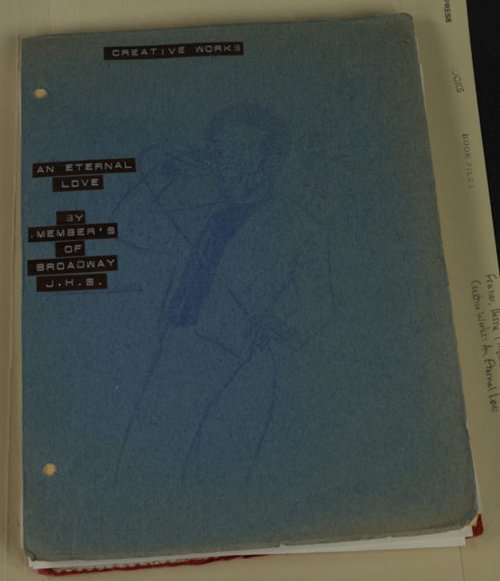

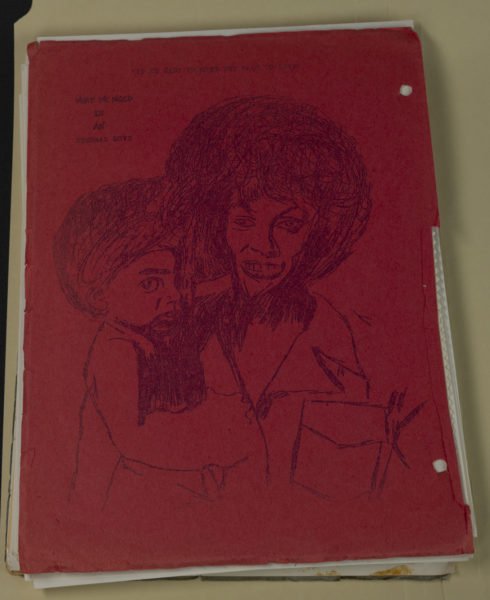

Front cover of Bessie Frazier's Creative Works: An Eternal Love By Members of Broadway Junior High School, Grove Press Records

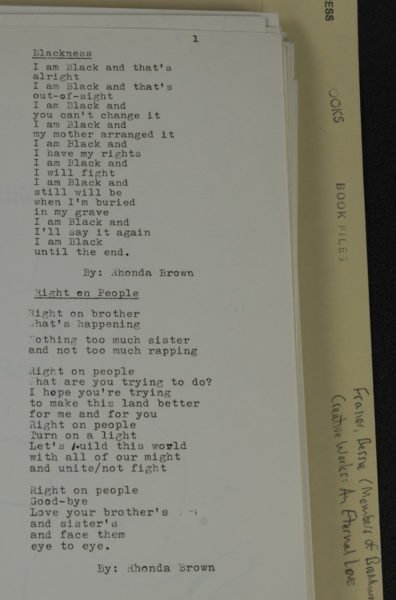

Two poems by Rhonda Brown

Back cover illustration of “An Eternal Love”

The cover features an illustration of James Brown and, in fact, "Say It Loud – I'm Black and I'm Proud", seems to be echoed in the opening poem by student Rhonda Brown. Within the manuscript is poetry and prose, short stories, plays, slogans, statements and questions from contributing students showcasing their own art contributions.

I am Black and that’s

alright

I am Black and that’s

out-of-sight

I am Black and

you can’t change it

I am Black and

my mother arranged it

I am Black and

I have my rights

I am Black and

I will fight

I am Black and

still will be

when I’m buried

in my grave

I am Black and

I’ll say it again

I am Black until the end.

"Blackness" by Rhonda Brown

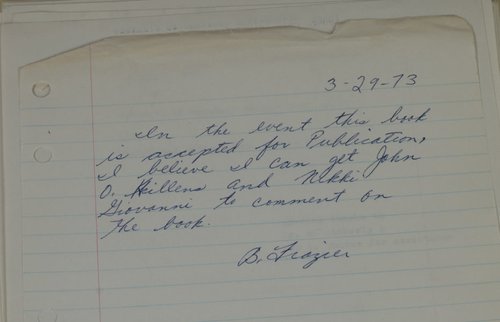

Bessie Frazier, a teacher at Broadway Junior High School, submitted this collection of student work (as editor and author) to Grove Press. Prior to being a teacher, she was a member of Fisk University’s Writer’s Workshop where she studied with important Black voices, mainly those of Nikki Giovanni and John O. Killens. This incredible snapshot into the lived experiences of Frazier and her students helps us to better understand actual perspectives of students and teachers learning during the time of the Black Arts Movement.

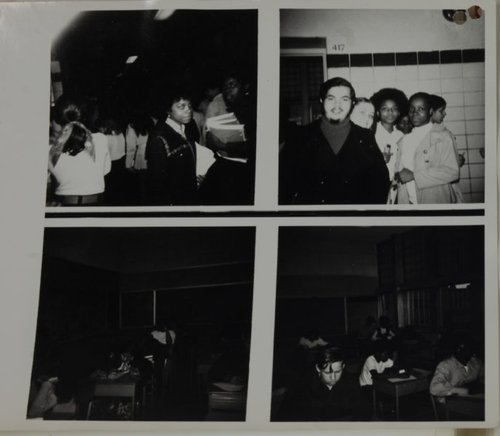

Silver gelatin photographs of the students around school and in class are included mid-way in the manuscript.

Included in the manuscript was a handwritten note from Bessie Frazier to Grove Press.

Though not planned, the pop-up coincided with the #NotAgainSU student protests on campus, making the exhibition particularly poignant. Prompted by a series of acts of hate late in the fall 2019 semester, that have continued surfacing into the spring 2020 semester, BIPOC students have called for administrative action to support vulnerable students through the creation of spaces, funding and programs for students of color, and faculty and staff hires that better reflect student identities. This call for the condemnation and elimination of oppressive campus culture, and the vital need to make space for the sowing and proliferation of BIPOC cultures for themselves, could have come from the very pages of materials featured in this exhibition. The student movement can be followed on their social media accounts: @notagain_su on Twitter, and notagain.su on Instagram.

If you’re interested in learning more about the SCRC Black Arts Movement resources available, you can further explore the resources through an earlier SCRC Black Arts Movement online exhibition.

The WAER Collection (WAER Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) Collection (Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), and Grove Press Records (Grove Press Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Sources:

Baraka, Amiri. The autobiography of LeRoi Jones. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1997.

Fenderson, Jonathan. Building the Black Arts Movement: Hoyt Fuller and the Cultural Politics of the 1960s. University of Illinois Press, 2019.

Tinson, Christopher M. “New Breeds, Old Dreams: Liberator and Black Radical Aesthetics.” Radical Intellect: Liberator Magazine and Black Activism in the 1960s. Chapel Hill:University of North Carolina Press, 2017. pp. 185-234.