Durable and Elegant: Mary Edwards Walker and Dress Reform

by Grace Wagner, Reading Room Access Services Supervisor

“Dr. Mary Walker may be eccentric, but she is no fool. On election day, she offered her vote in Oswego; and it was refused on account of her sex. A bystander remarked that, if Mary was allowed to vote, ‘they might as well dress up all their women-folks in men’s clothes, and bring them down and vote them.’ To which Mary indignantly replied: ‘I don’t wear men’s clothes, I wear my own clothes.’ Exit the masculine voter.”

Vineland Independent, 1880

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker achieved national recognition in the 19th century for her service as a surgeon in the army during the Civil War. She was awarded the Medal of Honor for her service in 1865, the only woman to receive this honor to this day (the award was revoked in 1917 and restored in 1977). Despite her accomplishments in this arena, in later years she was known largely as an “eccentric” to the majority of the United States population, an impression that followed her until her death in February 1919 at the age of 86. This impression of eccentricity, as the above account indicates and confirms, was awarded to Walker not solely (or even primarily) because of her work as an army surgeon, but largely due to the “men’s clothes” she exclusively attired herself in at this point in time. Although Walker did not outfit herself in waistcoats and trousers until later in her life, dress reform was a battle that she had been waging from the early days of her life.

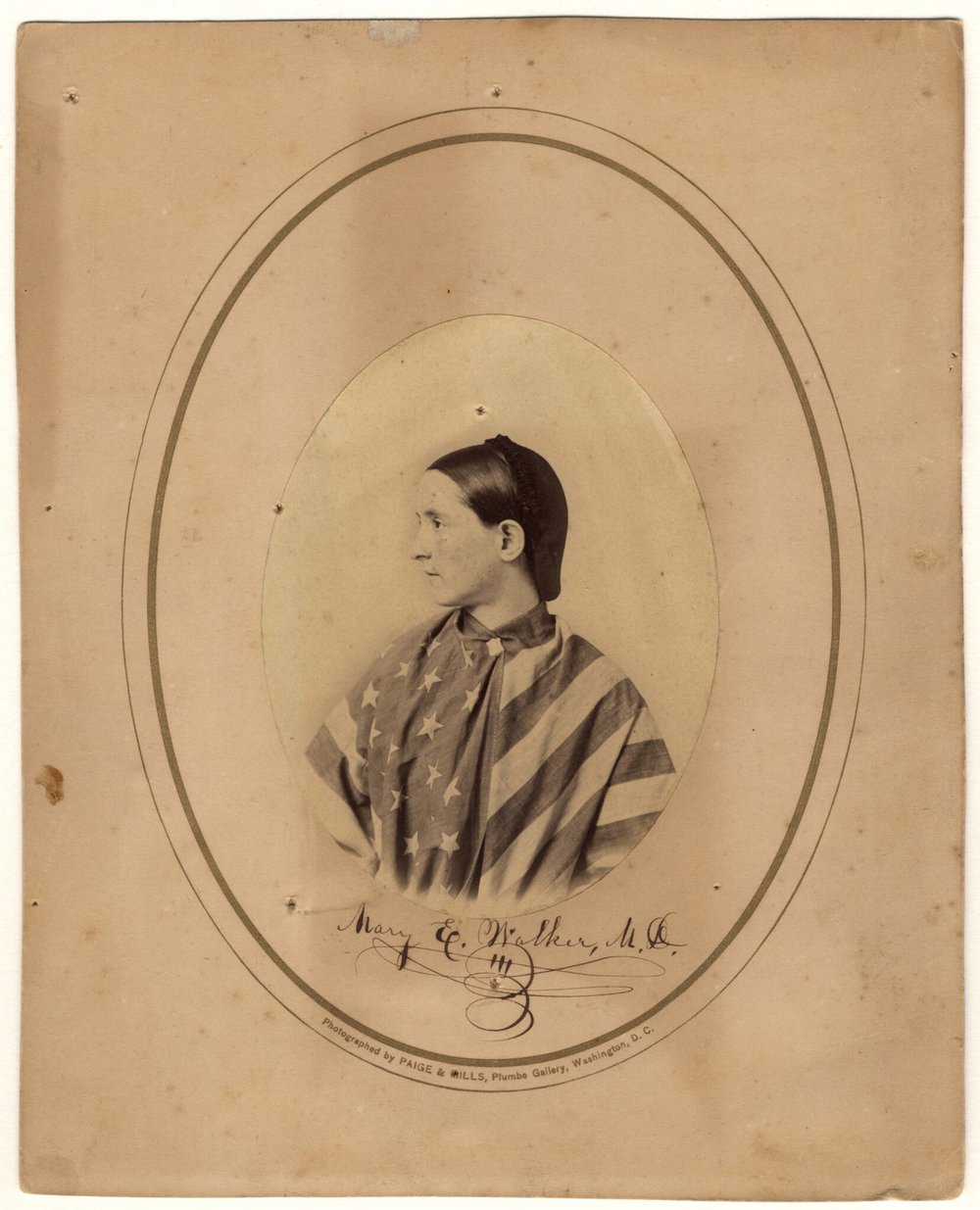

Oval portrait photograph of younger Walker, left profile, wearing American flag draped over her shoulders, handwritten below is “Mary E. Walker, M.D.” photographed by Paige & Mills, Washington, D.C. Mary Edwards Walker Papers.

Dress reform was not a frivolous pursuit to Mary Edwards Walker. She consistently positioned this cause at the center of her reform efforts. In her first book, Hit, published in 1871, Walker devotes her second — and longest — dedication (the first dedication reads in full “To My Parents”) to her fellow dress reformers:

“TO THE PRACTICAL DRESS REFORMERS,

The truest friends of humanity, who have done more for the universal elevation of woman in the past dozen years, than all others combined. You, who have lived the precepts and principles that others have only talked—who have been so consistent in your ideas of the equality of the sexes, by dressing in a manner to fit you for the duties of a noble and useful life. You, who have written and spoken, and been living martyrs to the all-important principles involved in a thoroughly hygienic dress, and thus given to the world and indisputable proof of your unflinching integrity. To You, in a word, who are the greatest philanthropists of the age, this second Dedication is made.”

Hit, Mary Edwards Walker, 1871

Repeatedly, Walker made her arguments for dress reform on the basis of hygiene, health, and greater mobility. She did not see how equality between the sexes could be achieved if women were not able to easily move and thus perform the same, or similar, work as men.

Bystanders, cartoonists, and reporters leveled a steady stream of abuse, jokes, and complaints at Walker for decades for dressing as she did, many of which are recorded in newspaper articles and editorials. By her own account, Walker was regularly harassed on the street and arrested more than a dozen times for the way she dressed. Many individuals thought — and many newspapers of the time perpetuated the narrative — that Walker had been granted special dispensation from the government to dress in trousers, despite the fact that it was not illegal for women to do so and no such dispensation actually existed.

In Walker’s papers and correspondence held at SCRC, some particularly persistent individuals even crafted letters and sent their complaints and corrective dialogues straight to Walker herself.

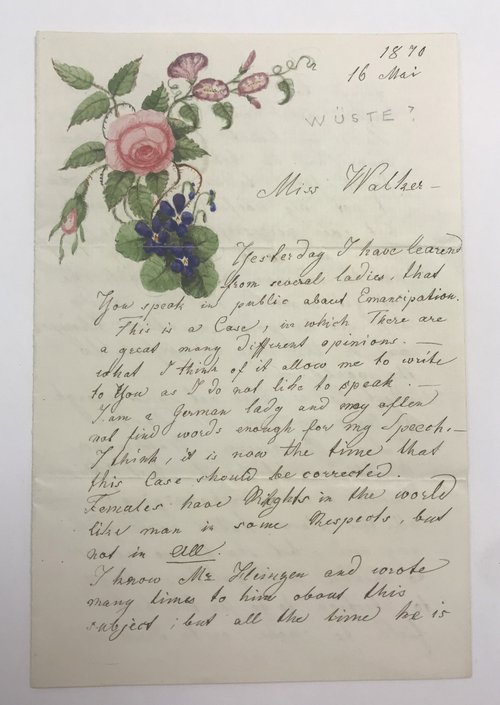

The front of Louise Wüste’s letter addressed to “Miss Walker,” featuring a floral illustration from 1870. Mary Edwards Walker Papers.

One of the most interesting of this group of letters, sent to Walker in 1870, is covered in delicate script and a beautiful illustration of a pink rose flanked by morning glories and purple violets (symbolizing modesty and faithfulness). The letter, written by Louise Wüste, a self-described “German lady” and “Artist,” reads, in part:

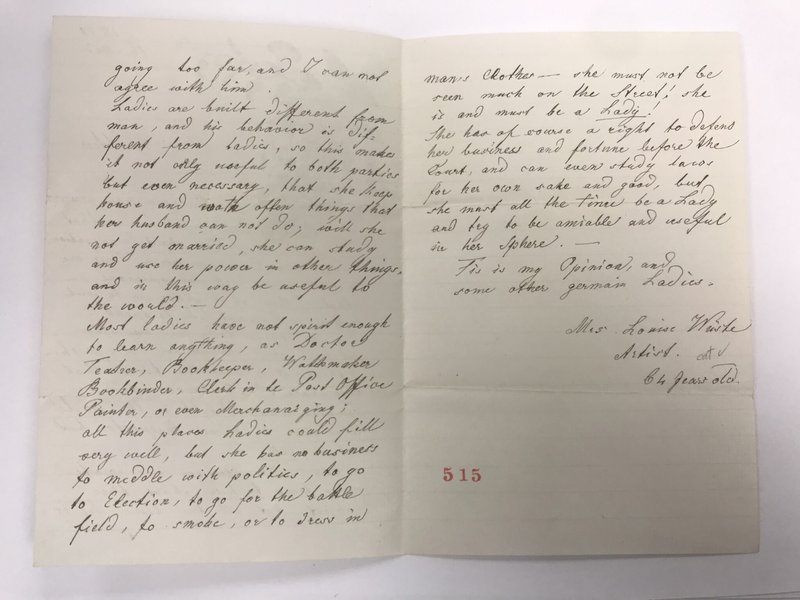

“Females have Rights in the world like man in some Respects, but not in All...Most ladies have not spirit enough to learn anything, as Doctor[,] Teacher, Bookkeeper, Watchmaker[,] Bookbinder, Clerk in the Post Office[,] Painter, or even Merchanaiging [Merchandizing]; all this places Ladies could fill very well, but she has no business to meddle with politics, to go to Election, to go for the battle field, to smoke, or to dress in man’s clothes — she must not be seen much on the Street! She is and must be a Lady!”

Louise Wüste, excerpted from a 16 May 1870 letter

The inside pages of Louise Wüste’s 1870 letter to Walker, featuring her criticism of Walker’s style of dress. Mary Edwards Walker Papers.

Although Wüste asserts that women have the right to work as doctors or painters, she also addresses her letter to “Miss Walker,” effectively discounting Walker’s medical degree and work as a surgeon. Wüste makes it clear that she does not approve of Walker’s presumption to “meddle with politics” and least of all “dress in man’s clothes,” as these behaviors contradict with one’s ability to act as a lady. Read in this light, the delicate flowers on the front of the letter seem to be less a decorative touch from an admirer and more a pointed attack on someone who did not fit the mold of womanhood as the correspondent saw it.

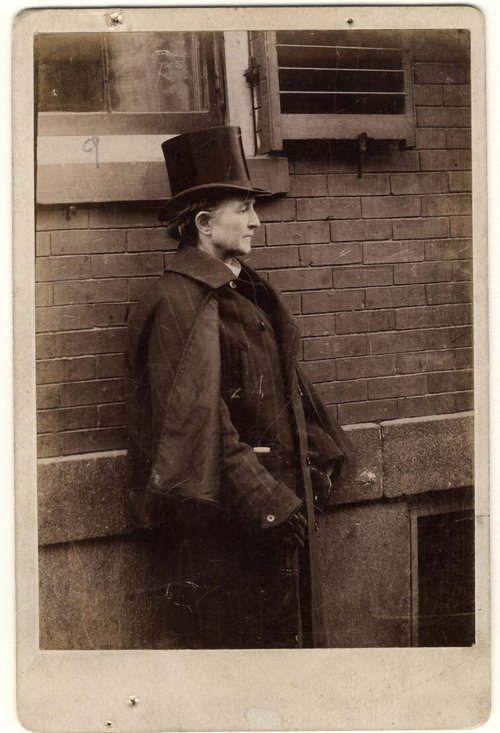

In reading Walker’s letters and documents, however, it is clear that Walker’s preference for trousers did not preclude her enjoyment of fashion or fashionable garments. In the photographs where she is dressed in bloomers or suits, she is elegantly put together and appears to have had a taste for beautiful and rich garments.

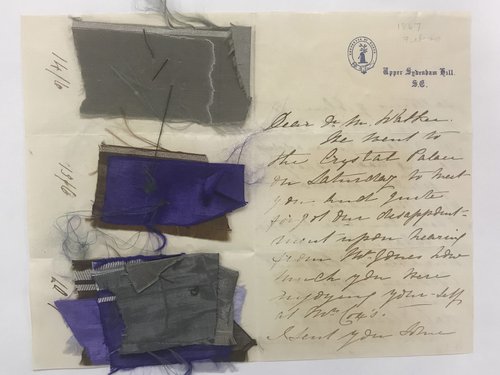

The front of the letter addressed Dr. Walker sent in 1867 during Mary Edwards Walker’s speaking tour in England. Mary Edwards Walker Papers.

A February 1867 letter affirms this fact, sent to Walker by an Englishwoman, Anne Cooper, just a few years before Louise Wüste’s letter. The years 1866 and 1867 encompassed a transitory time for Mary Edwards Walker. She was still wearing bloomers and the modified uniform of her Civil War years, but she was beginning to move towards the dandified suits she adopted in later years — trousers, waistcoat, and top hat included. She was also riding the height of her Civil War fame. Like others who received a burst of celebrity from the Civil War, she capitalized on this, embarking on a speaking tour in England during this time.

Like Wüste’s letter, Cooper’s letter is also adorned with traditionally female decoration. Unlike the neat, elegant lines of the flowers drawn by Walker’s critic, however, the rich, fraying squares of cobalt blue, royal purple, and gunmetal gray are attached to the back of the document with large, uneven stitches:

“I sent you some patterns of blue to Mrs. Cox’s Hotel having forgotten your address having had no responce [sic] [.] Suppose discord predominates. I here enclose a choice of what I think – durable & elegant colours hoping to see you on Thursday.”

Anne Cooper, excerpted from a letter dated February 1867

These “durable & elegant” choices are offered alongside details of a trip to the Crystal Palace and hints of past and future social engagements. They appear to be the words of a friend.

Mary Edwards Walker standing next to building, wearing top hat and men’s overcoat, undated. Mary Edwards Walker Papers.

The pieces of fabric attached to this letter may be the only samples held in the Mary Edwards Walker Papers at SCRC, and while we may never find out if the garments in question were ever made for Walker, or what colors she chose if they were, these small samplings help us to better understand Walker, her beliefs, and the way she chose to present herself to society. Walker was a complicated and a complicating figure and her choices moved her outside of the standards set by society and other reformers. She refashioned a new position in society for herself, one where she could serve as a surgeon and support causes that she loved and where she could dress how it pleased her to dress, deferring only to her own selection, rather than one imposed upon her.

The Mary Edwards Walker Papers (Mary Edwards Walker Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Additional Sources

Burgess, Anika, “The Unconventional Life of Mary Walker, the Only Woman to Have Received the U.S. Medal of Honor.” Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/mary-walker-feminist-dress-reform-equal-rights (accessed June 1, 2020).

“Dress Reform.” Freethought Trail. https://freethought-trail.org/causes/cause:dress-reform/(accessed June 1, 2020).

Fischer, Gayle V. 2001. Pantaloons & Power: A Nineteenth-century Dress Reform in the United States. Kent State University Press. 148-154. Google Books.

Potter, William J., and B. F. Underwood. 1880. Free religious index. Boston: Free Religious Association. 299. Google Books.

Walker, Mary Edwards. 1871. Hit. New York: American News. Internet Archive.

“Women in History. Mary Edwards Walker biography.” Women In History Ohio. http://www.womeninhistoryohio.com/mary-edwards-walker.html (accessed June 1, 2020).