Lifting as we climb: Mary Church Terrell and the 19th Amendment

by Grace Wagner, Reading Room Access Services Supervisor

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting women in the United States the right to vote. Although the amendment was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, it could not be added to the U.S. Constitution until 36 states approved the amendment. Tennessee was the 36th state and approved the amendment on August 18th, 1920, by a narrow margin. Other states continued to approve the amendment in a small trickle over the remainder of the 20th century, with the most recent ratification occurring in Mississippi on March 22, 1984, a stark reminder of the sometimes plodding nature of progress.

This slow march forwards, interspersed with epochs that seemed to lurch backwards, is characteristic of the fight for suffrage in the United States. One of the leaders of the suffrage movement, Mary Church Terrell, understood the gradual nature of change better than most.

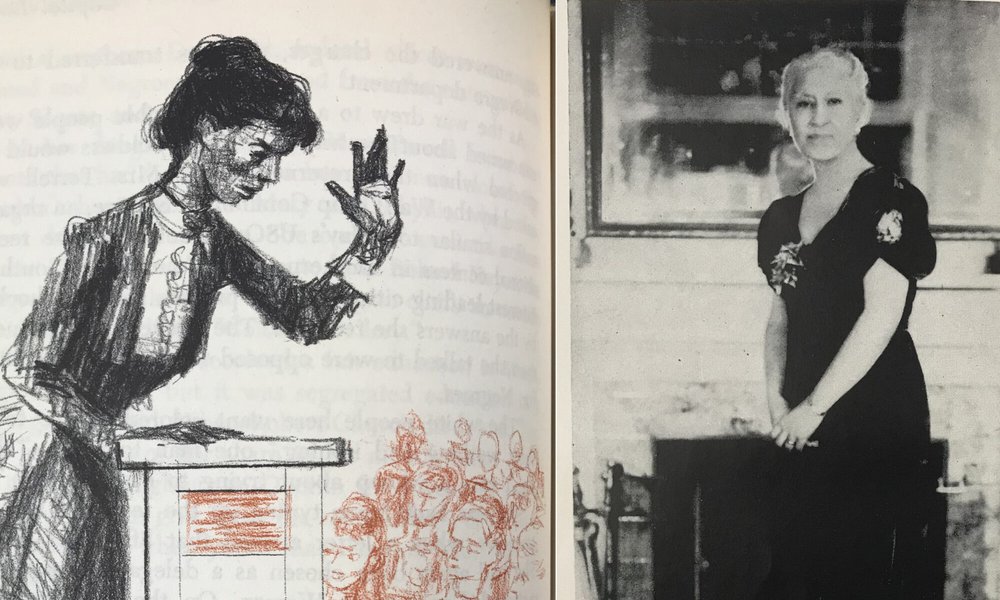

A photograph of Mrs. Mary Church Terrell that features in the inside of her book cover, A Colored Woman in a White World, 1940.

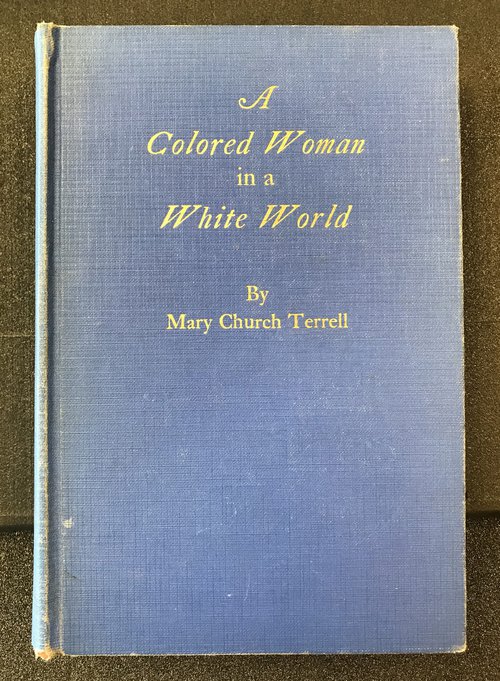

A lifelong activist, Mary Church Terrell lived in Washington, D.C. for much of her life and never stopped advocating for herself and others during the 90 years of her life. Early on, Terrell engaged in promoting educational reforms in the Black American community, took part in anti-lynching campaigns, and expanded the goals and viewpoints of the suffrage movement. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, as she neared her 90th birthday, Terrell continued to advocate for her community, protesting segregation in restaurants, schools, and public places.

Suffrage was one of the first causes Terrell took up in the 1890s and she consistently fought for the cause in two spheres. Utilizing the already-strong networks of church and club organization existing among Black women in the D.C. area, Terrell helped form the Colored Women’s League (CWL) in 1892 and later, in 1896, organized and became the two-times president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which adopted the motto, “Lifting as we climb,” an acknowledgement that the NACW fought for progress across lines of both gender and race, not only for voting rights for women.

Terrell did not allow her voice to disappear within the crowd. She picketed the White House with the National Women’s Party, led by Alice Paul and a small faction of devoted advocates, and she attended meetings of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, led by the mainstream white leaders of the suffrage movement, including Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott. Although Terrell was eventually welcomed at these meetings, it was clear that her voice, insight, and point of view had been sorely missing from the group up until this point. She spoke up at the meetings, even when she was not a member, and advocated for herself and other Black women in the country. She saw the value in operating in two spheres, both in advocating for her community separately and in moving the concerns of the Black community into the mainstream.

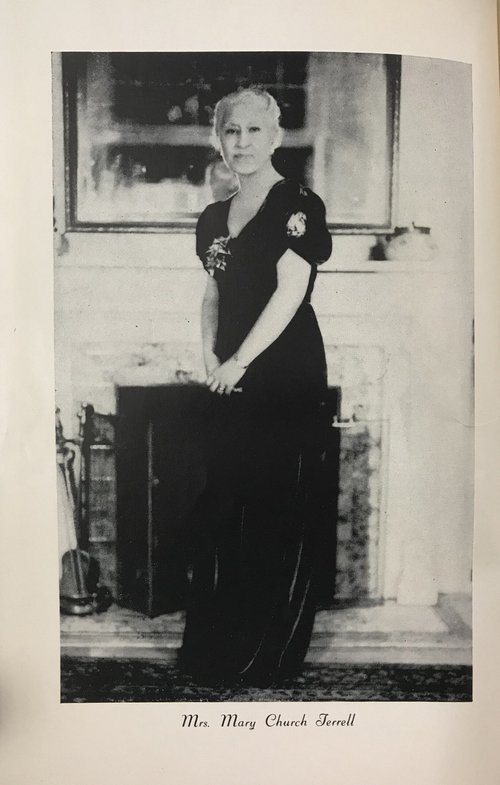

An illustration of Mary Church Terrell addressing the International Congress of Women, illustrated by Ernest Crichlow from Lift every voice, 1965.

Intersectionality was not widely acknowledged by the public-facing, white leaders of the suffrage movement, and prominent Black female advocates, like Mary Church Terrell, presented the realities of the different experiences of these groups of women in a straightforward and unflinchingly honest manner. At the time of its passage, Terrell noted the impact of the 19th Amendment on women of the nation:

“By a miracle the 19th Amendment has been ratified,’ I wrote. ‘We women have now a weapon of defense which we have never possessed before. It will be a shame and reproach to us if we do not use it. However as much the white women of the country need suffrage, for many reasons which will immediately occur to you, colored women need it more.”

Mary Church Terrell, A Colored Woman in a White World, p. 310

Though Terrell voiced her feelings at the time of the 19th Amendment’s ratification, she would echo and expand upon these thoughts in her 1940 autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World.

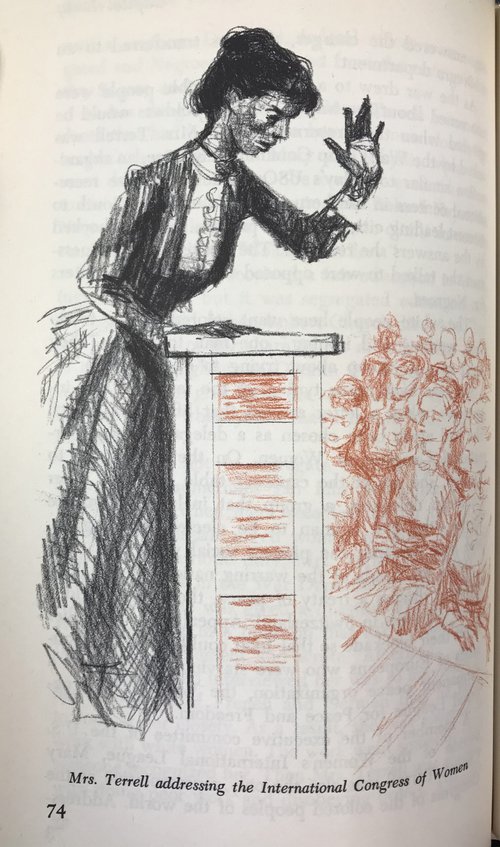

The cover of the 1940 edition of Mary Church Terrell’s autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World. A Colored Woman in a White World, 1940.

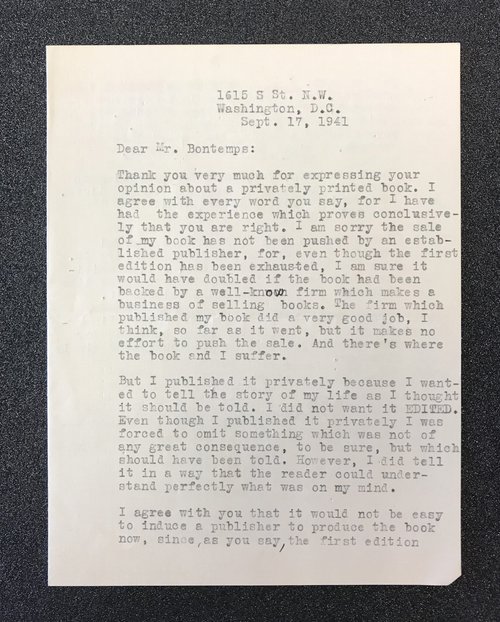

Shortly after the book was published, Terrell exchanged letters with the poet and writer Arna Bontemps on the sales of her book. In her letters, Terrell asks for Bontemps’ advice on funding a second printing, perhaps through the support of a major publisher. She describes to him some of the difficulties she faced on submitting her manuscript to publishing houses, before electing to publish the book privately:

“I do not understand publishers at all. From the nature of the case, the first autobiography written by a colored woman with a career similar to mine would be likely to sell if a well-know firm backed it. Two of the largest publishing houses in the country kept my book a long time…When they returned the manuscript, they declared it was a very good book, but the sales people feared they could not sell it.”

Mary Church Terrell, excerpt from a letter dated September 17, 1941

In a fascinating exchange of letters, Terrell and Bontemps discuss the difficult nature of publishing books by and about the Black experience in America and the unwillingness of publishers to trust in Black authors and readers as a viable, reliable market for books. Like many institutions in American today, the depressingly narrow demographics of the publishing industry have changed very little in the past 80 years.

In a telling echo of Terrell’s experiences during the suffrage movement, Terrell and Bontemps also discuss women’s book clubs as a potentially potent market for Terrell’s book. Terrell acknowledges that while there is a existing audience of white female readers for her book, the publishing industry has failed to acknowledge the large untapped market of Black female readers that she feels her book could be effectively marketed and sold to as well.

The first page of one of Mary Church Terrell’s letters sent to Arna Bontemps concerning her reasons for privately publishing her autobiographical book. Arna Bontemps Papers.

Terrell’s choice to publish her book privately was based on a number of different factors, but in an echo of her suffrage movement experience, it was partly due to lack of buy-in from people in positions of power. In choosing to privately publish her book, however, Terrell also demonstrates her valuation of publishing the book that she wanted to publish, and not one that had been heavily edited by a editor’s pen. She writes in the same letter:

“But I published it [the book] privately because I wanted to tell the story of my life as I though it should be told. I did not want it EDITED. Even though I published it privately I was forced to omit something which was was not of any great consequence, to be sure, but which should have been told. However, I did tell it in a way that the reader could understand perfectly what was on my mind.”

Mary Church Terrell, excerpt from a letter dated September 17, 1941

In our popular imagining, the suffragette has taken on a set of stock characteristics. She is outfitted in a pristine floor-length white dress, perhaps wearing a “Votes for Women” sash, white gloves, white hat, and carrying a picket sign in protest standing in front of the White House. And she is white.

Although not inaccurate, this view of the suffragette and the suffrage movement is incomplete. And while this view acknowledges some of the voices of the movement, much like the mainstream pioneers of the suffrage movement and the major publishing houses who returned Terrell’s manuscript back to her, it does not acknowledge the untapped power of all of the voices still to be heard.

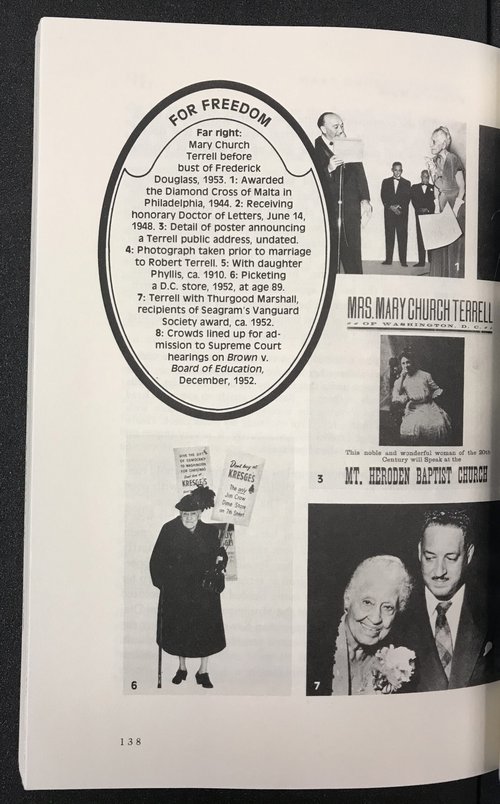

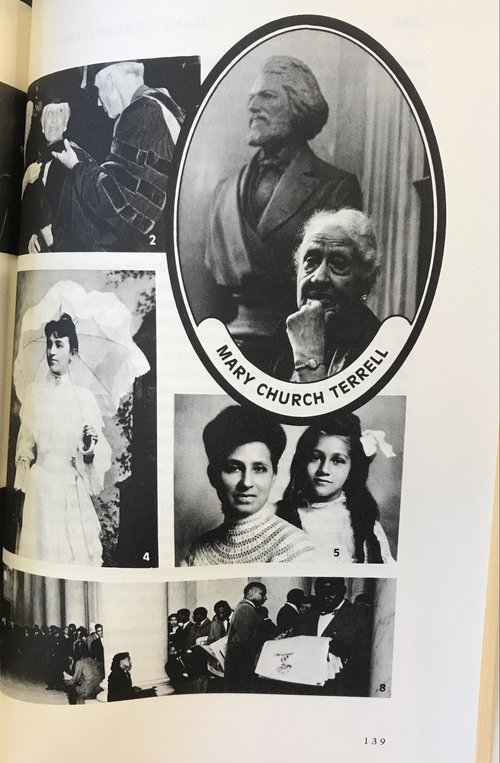

A photo collage of photographs of Mary Church Terrell through the years. Black foremothers: three lives, 1979.

A photo collage of photographs of Mary Church Terrell through the years. Black foremothers: three lives, 1979.

On August 18th, 1920, Mary Church Terrell’s home state, Tennessee, became the 36th state to approve the 19th Amendment. With this approval, the United States reached the 36 states required to add the amendment to the constitution. Terrell’s birth year, 1863, was marked by the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, and she died in 1954, only two months after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. Near the mid-point of her life, the 19th Amendment was passed, a reminder for Terrell then, and us today, that while some progress has been achieved, there is still a very long way to go.

The images featured in this post are from our rare books collection (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and our Arna Bontemps Papers (Arna Bontemps Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Additional Sources:

Terrell, Mary Church. 1940. A colored woman in a white world. Washington, D.C.: Ransdell Inc.

Sterling, Dorothy. 1979. Black Foremothers: three lives. Old Westbury, N.Y.: The Feminist Press.

Sterling, Dorothy, Benjamin Quarles, and Ernest Crichlow. 1965. Lift every voice: the lives of Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary Church Terrell, and James Weldon Johnson. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.