Reconstructing Racial Equality in Syracuse

by Krystal Cannon, SCRC Curatorial Instruction Assistant

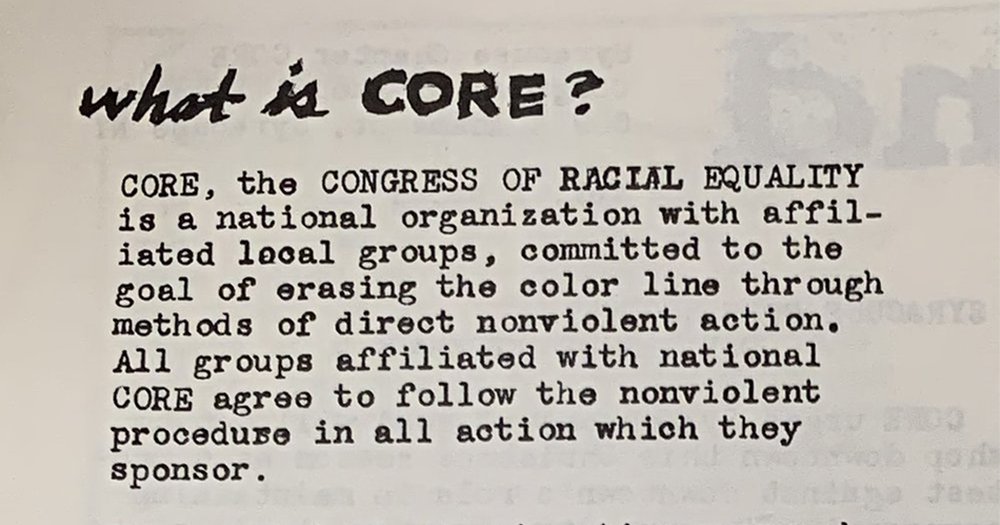

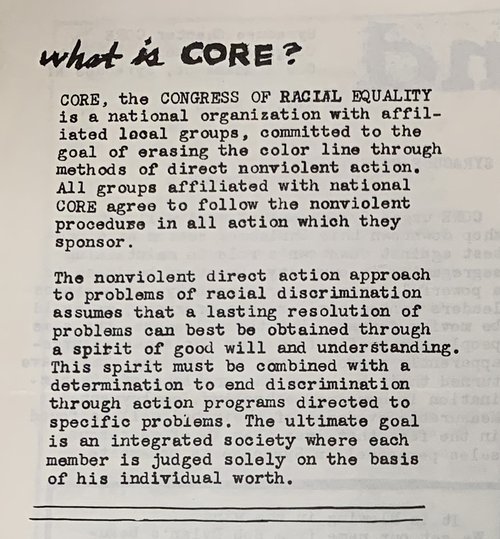

The history of roads and highways may not immediately seem contentious, but Syracuse’s Interstate 81 has played a major role in the racial, social, and economic landscape of the city. With social justice coming to the forefront of popular discourse throughout this past year, it’s important to understand how the injustices of history have impacted the realities of the present. SCRC is fortunate to hold a bit of this history within the Congress of Racial Equality (Syracuse Chapter) Collection. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded in Chicago, Illinois in 1942, with chapters forming across the country throughout the next two and a half decades. Though their national impact had dissipated by the end of the 1960s, they played an important part in the Civil Rights Movement at the height of their influence, focusing on empowering Black communities to demand an end to racial injustice through boycotts, demonstrations, and other forms of nonviolent direct action.

Description of CORE from the first issue of their newsletter “In the Wind.”

I-81 was erected in 1957 and ran directly through Syracuse’s 15th Ward, leading to the destruction of people’s livelihoods and upending the culture and relationships that neighbors had built with one another. Prior to the emergence of CORE’s Syracuse chapter, residents of this district protested the highway’s construction by picketing outside of buildings in danger of being demolished, which were sometimes their own houses. This area was home to a majority of Syracuse’s Black residents, many of whom had relocated here after World War II to find better employment opportunities than existed further south. Due to the increase in personal vehicle ownership and travel, highways were being built nationwide, and it was common that Black redlined neighborhoods were sacrificed as part of this initiative. There was little representation in government on local and national levels to protect these communities from the federal investment in racist infrastructure, and attempts to stop it went unheard.

A few years later, urban renewal programs endeavored to gentrify what remained of the 15thWard. Homes and recreational landmarks in this community were destroyed to make way for newer housing, as well as businesses and offices. CORE advocated for these displaced Black residents as discriminatory practices continued to ensue in less visible ways. As Black families sought new housing in other parts of the city, they were often lied to about availability and pricing in predominantly white neighborhoods. CORE activists and community members tested this by sending white families to inquire about the same properties, who were given different information and treated as welcomed customers.

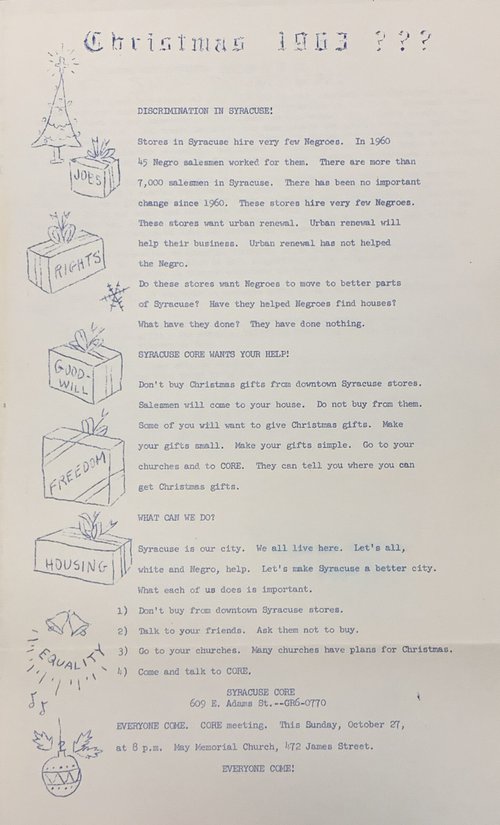

This also led to a need for 15th Ward residents to find new employment. Black individuals were often denied job opportunities in this so-called renewed area, which inspired CORE’s Christmas boycott in 1963. This call to action discouraged shopping in Syracuse’s downtown area in support of Black-owned businesses and services. This boycott also pushed a list of demands prompting businesses to take action against racial injustice by changing their hiring policies and speaking out in support of civil rights legislation.

Christmas 1963 boycott guide distributed by CORE.

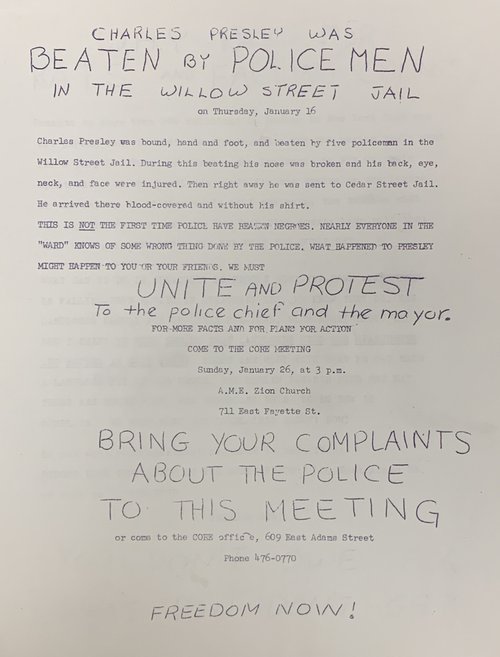

Additionally, CORE tirelessly worked to find justice for Black individuals who had been mistreated by police officers in a fashion strikingly similar to what we’ve seen throughout the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. Press releases were used to encourage the community to take part in contacting officials and joining demonstrations. Countless other social and systemic issues were tackled by the group, who, on top of their press releases, produced pamphlets and booklets to educate the community about the many different ways in which racial discrimination and half-measures towards equality were leaving a huge population of Syracuse underserved. Unfortunately, because the previous residents of the 15th Ward had become scattered around Syracuse and its surrounding areas, activist momentum in Syracuse inevitably wavered. The ability to organize against injustice collectively became increasingly difficult and CORE was unable to continue its advocacy effectively.

Call to action organized by CORE to protest police brutality in 1964.

The 15th Ward may no longer exist, but I-81 continues to wreak havoc on residents living along the elevated highway. Some homes are mere feet away from the busy thoroughfare, making exhaust fumes and traffic noise inescapable. This interstate was not designed to be permanent, and, in passing its expiration date, has jeopardized its structural integrity and safety. Many have hoped for the seizure of this opportunity to devise a better plan, and activists and city officials have been attempting to find new ways to move forward that do not include the reconstruction of this highway. Proposals have been put forth to improve the quality of life for nearby residents and communities, including more green space, greater walkability, and better access to local businesses. Details for how the city plans to proceed have not yet been finalized, but it’s clear that Syracuse residents deserve some form of amends to honor the struggles of past activists and meet the needs advocated for by current ones.

The Congress of Racial Equality (Syracuse Chapter) Collection (Congress of Racial Equality (Syracuse Chapter) Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) is part of Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.