Selling the Soapbox

by Courtney Asztalos, Plastics and Historical Artifacts Curator, and Grace Wagner, Reading Room Access Services Supervisor

Hand-washing is not a passive act these days. It is careful, deliberate, systematic. Labels of soaps and hand sanitizers are inspected closely for germ- and bacteria-fighting power. And advertising agencies and soap manufacturers are coming up with new ways to market their products to fit the importance of this action. As strange as all of this may seem, manufacturers are doing what they have always done — responding to the current moment and state of mind of the consumer. Let’s journey back through SCRC’s collections to see how soap was packaged and sold throughout the 20th century.

"On The Streetcar Where You…Advertise"

1909

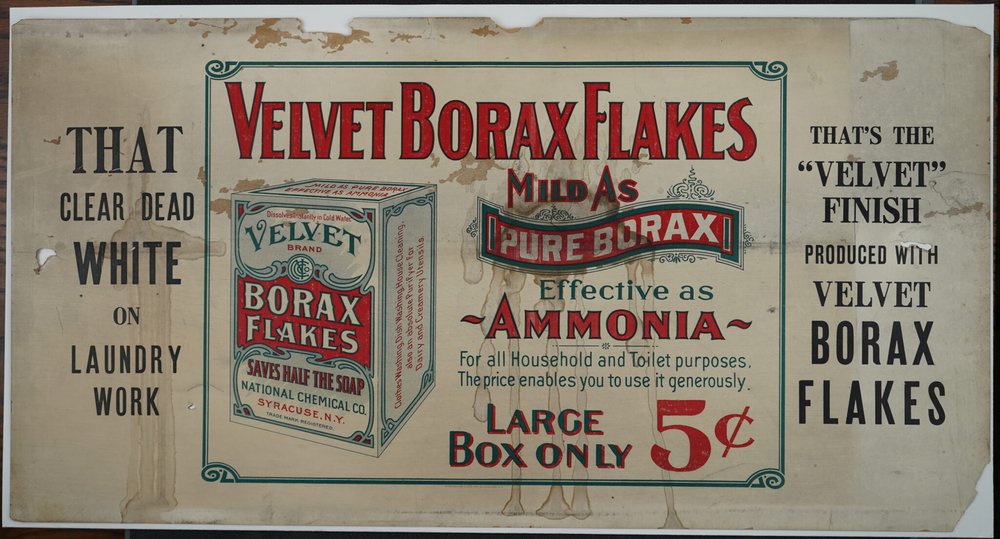

The 1909 streetcar advertisement for Velvet Borax Flakes produced by the National Chemical Company located in Syracuse, N.Y. Lyall D. Squair Streetcar Advertisements Collection.

Colorful cardboard cards with convincing bylines and illustrated depictions of products dotted the windows of streetcars in the early 20th century. At this time, streetcars had become a major means of transportation in American cities, effectively responsible for expanding the scope of the city, as they enabled suburbanites to commute to work in the city on a daily basis for extremely cheap rates. And streetcar advertising became a means of advertising products to a wide audience of city travelers. SCRC’s Lyall D. Squair Streetcar Advertisements Collection contains two dozen of the classic 11 x 21 cardboard signs that hung in the windows of streetcars, including an ad for the National Chemical Company’s “Velvet Borax Flakes.” In bold red, green, and black text, the advertisement promotes the product’s all-purpose effectiveness for clothes washing, dish washing, and household cleaning. The box, priced at 5 cents, less than many streetcar fares of the time, had a right to claim, “The price enables you to use it generously.” The National Chemical Company had moved to Syracuse in 1904, as the “Salt City” was the center of alkali production at that time. (Grace Wagner)

"Being Parlor Wise is Being Beauty Wise"

1929

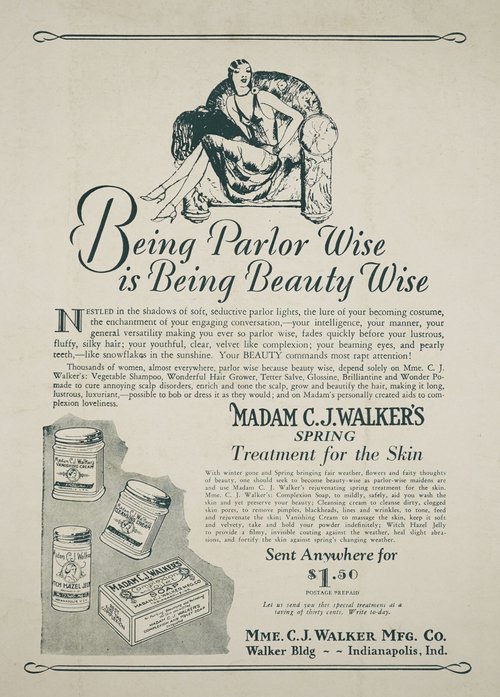

“Mme. C. J. Walker’s: Complexion Soap, to mildly, safely, aid you wash the skin and yet preserve your beauty,” Madame C.J. Walker’s Spring treatment for the skin advertisement, Back cover of The Crisis Magazine, April 1929.

Madame C.J. Walker’s advertisements grace the back cover of many of the issues of The Crisis held here at SCRC. W.E.B. Du Bois’ famous magazine is chock-full of a stunning range of advertisements for Walker’s beauty products, ranging from hair products, to cosmetics, and complexion soap! This advertisement reads: “With winter gone and Spring bringing fair weather, flowers and fairy thoughts of beauty, one should seek to become beauty-wise as parlor-wise maidens are and use Madam C.J. Walker’s rejuvenating spring treatment for the skin.”

Sarah Breedlove, later known as Madame C.J. Walker, was famous for her innovation and formulas in the early 20th century that led her to establish “The Walker System of Beauty Culture,” and subsequently train “beauty culturists,” establish the Lelia College of Beauty Culture, and found the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the legacy and brand of which still exists today. Walker is recorded as the first Black American self-made female millionaire in the United States. Above, we see the gorgeous soap box of Walker’s advertisement from the 1929 issue of The Crisis. The “Complexion and Toilet” soap’s packaging in the advertisement suggests its quality is “unequaled” in its promise of use for “purifying, beautifying and refreshing the skin.” (Courtney Asztalos)

“And Now, A Word From Our Sponsor”

circa 1930

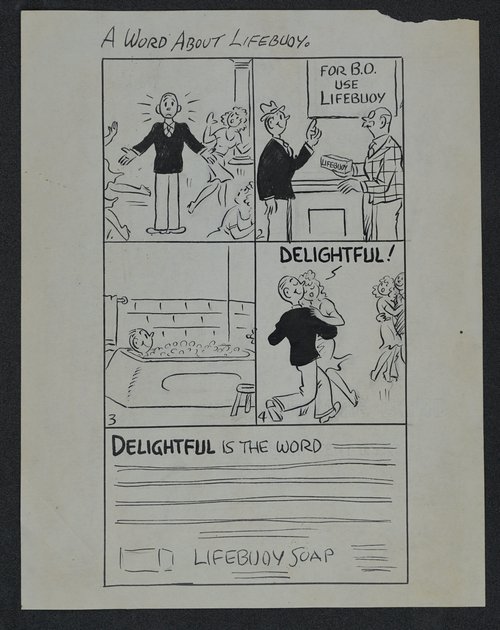

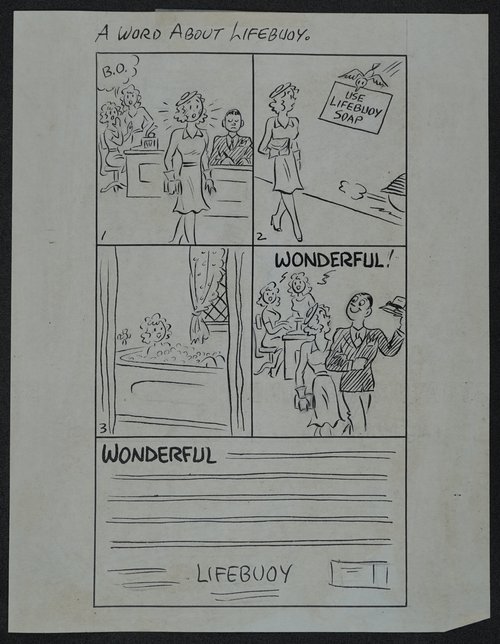

An advertisement for Lifebuoy Soap, detailing how to deal with B.O., designed by Alvah Posen in the 1930s. Alvah Posen Papers.

An advertisement for Lifebuoy Soap, detailing how to deal with B.O., designed by Alvah Posen in the 1930s. Alvah Posen Papers.

You might remember Lifebuoy as the soap that nearly “poisoned” Ralphie in the movie, A Christmas Story. Lifebuoy was introduced in the late 1800s in the United Kingdom and had its heyday in the 1920s through the 1950s when perfumed soaps were heavily in vogue. Lifebuoy, as Ralphie attests, has a distinctive, medicinal fragrance that made its marketing campaigns, focused on personal hygiene, a natural fit for the company. This can be seen in the above undated Alvah Posen advertisements for the brand, which focus on pleasing your romantic partner through good hygiene, as evidenced by the concerns of “B.O.” in the first panels of each cartoon. Contrary to popular belief, Lifebuoy did not coin the term, “B.O.,” but its use in their advertisements in the 1930s led to its popularity and widespread colloquial use.

The caption for these print advertisements, “A Word About Lifebuoy,” may bring another medium to mind: Radio. In the 1930s, radio programming began to pay attention to its “daytime” audience, predominantly made up of women, and the family drama-driven radio programs marketed to these consumers were accompanied by soap, deodorant, and cleaning advertisements. The soap-sponsored dramas led to the rise of the term “soap opera,” a usage that persists to this day. (Grace Wagner)

"Did you Design That?! "

1941

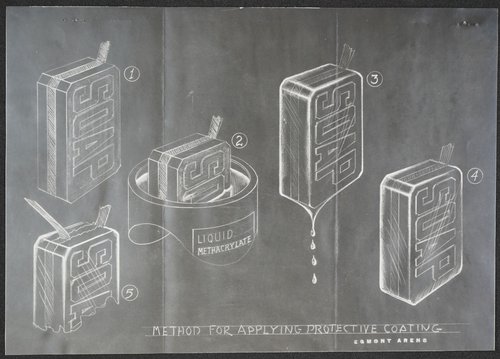

“Method for Applying Protective Coating.” Egmont Arens Papers.

At many drug stores, shoppers can still be influenced by “appetite appeal” in packaging design when shopping for a bar of soap. “Appetite appeal” signifies a consumer’s ability to see a product through the packaging, by observing a product’s texture, color and design through a thin film of plastic. This wasn’t always the case prior to the ubiquity of plastics packaging, as seen in previous soap packages like Madame C. J. Walker’s soaps and Velvet Ivory Flakes. However, with the rise of the field of Industrial Design in the mid-1920s, products and packaging were pushed to the consumer in ways that coalesced with the rise of the plastics industry’s domestication of product manufacturing. Egmont Arens was a leading innovator in plastics and product packaging. Arens, while largely respected for his unique industrial design contributions to everyday American objects, such as the subway turnstile and the meat slicer, often experimented with plastic and its new capacities as a consumer material.

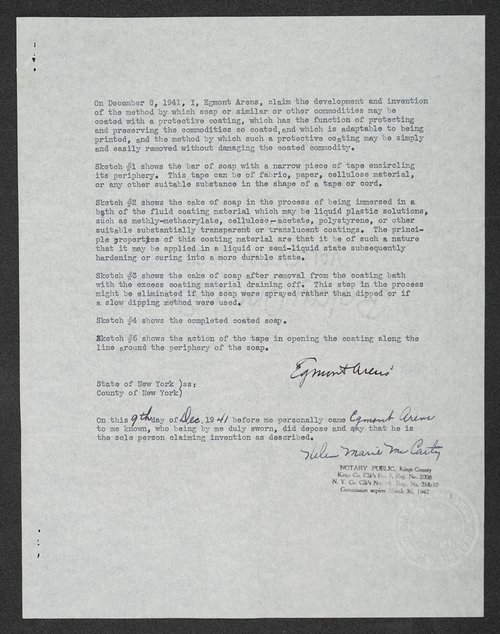

Egmont Arens’ claim for a “soap coating process” dated December 8, 1941. Egmont Arens Papers.

In 1941, Arens sent himself a legal claim to copyright his soap coating process via the USPS: “On December 8, 1941, I, Egmont Arens, claim the development and invention of the method by which soap or similar or other commodities may be coated with a protective coating, which has the function of protecting and preserving the commodities so coated, and which is adaptable to being printed, and the method by which such a protective coating may be simply and easily removed without damaging the coated commodity.”

As the drawing submitted with his claim demonstrates, the soap product could be immersed in a solution of liquid methacrylate, which would harden into a removable plastic coating. (Courtney Asztalos)

"Make Do and Spend"

1937-1942

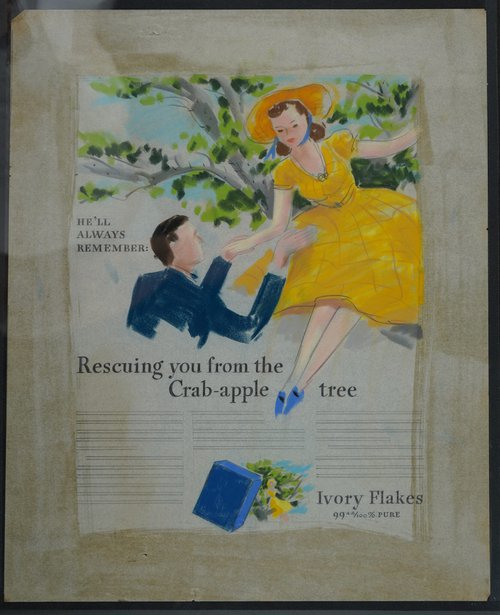

Sylvia Carewe’s undated advertisement for Ivory Flakes with the tagline, “He’ll always remember rescuing you from the Crab-apple tree.” Sylvia Carewe Papers.

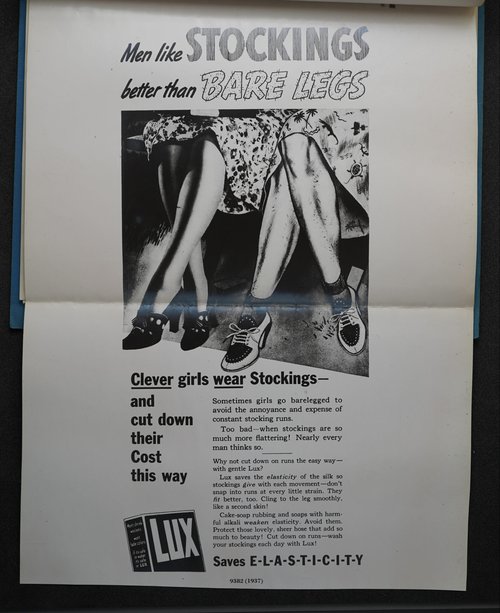

An undated Sylvia Carewe advertisement promoting Ivory Flakes soap trades on nostalgia. A faceless young man reaches his hand out to a girl sitting in a tree in a yellow dress and a bonnet, as the tagline proclaims, “He’ll always remember rescuing you from the Crab-apple tree.” In the 1930s, soap and stocking advertising partnerships took advantage of consumers’ tentativeness to invest in silk stockings, which could be delicate and expensive, by emphasizing the wash-ability of the garment with the respective soaps that they sold. A competing advertisement promoting the Lever Brothers’ Lux soap from 1937 to wash stockings for continued E-L-A-S-T-I-C-I-T-Y takes a more aggressive stance than Carewe’s approach by emphasizing the importance of wearing stockings because “Men Like STOCKINGS Better Than BARE LEGS.”

A 1937 advertisement for stockings and Lux soap proclaiming, “Men like STOCKINGS better than BARE LEGS.” Sylvia Carewe Papers.

When nylon, a synthetic fabric developed by DuPont, entered the commercial market in 1939, it quickly revolutionized the stocking industry. Almost as quickly, silk, and then nylon, the two fabrics the stocking industry was dominantly built on, were seized by the War Production Board for military supplies, within the first few months of the U.S. entering the war. An internal Ivory Flakes memo sent to Carewe dated September 4, 1941, anticipated the shortage of materials, or the “silk situation,” and noted, “Ivory Flakes is facing the difficult problem of keeping abreast of women’s stocking habits during this rapidly changing period.” Wartime shortages on the American home-front presented advertisers with a unique problem during World War II. How could they continue to market products, when consumers were being advised to ration and “make do” for their country? By July 1942, Ivory Flakes was employing the taglines, “Keep ‘Em Wearing!” and “Suds ‘Em and Save ‘Em!,” in an attempt to match their messaging to a wartime tone.

As the war continued, and stocking shortages reached new heights, Lux, Ivory Flakes, and other brands continued to revise their marketing strategies, as unprecedented numbers of women chose to forego stockings or covered legs, apparently far less concerned with what “men like” than the Lever Brothers wanted to believe. (Grace Wagner)

"Think Pink"

1959

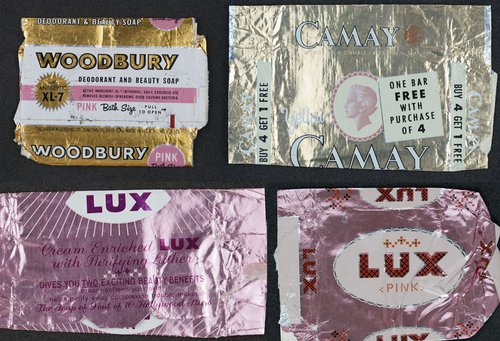

Soap packaging from various companies used in research and development of Lurelle Guild’s packaging redesign project for the Colgate Palmolive Company 1957-1959, Lurelle Guild Papers.

In 1959, Lurelle Guild was working with Palmolive to change the drab traditional olive tone of their Palmolive soap to “better match and blend” with home furnishings and beauty accessories, specifically targeting women as consumers. In a draft of his report based on surveys, Guild wrote: “There is no reason for Palmolive to keep its traditional green color alone… the present green color of Palmolive Soap rated a poor 8% in the green group.” He pointed to other soap manufacturers seen above in this grid of soap packaging, such as Lux, Woodbury, and Camay who “naturally, have this same group” of consumers. These other soap manufacturers were accessorizing with the color pink through these wrappers, but also advertised in other colors such as blue, white, green, and yellow. The choice for women to choose and accessorize their soap colors was clearly a trend. Much like Syroco promoted accessorizing with color through their line of Lady Syroco accessories for Bath & Boudoir at the end of the 1960s, ten years earlier, this lineage of centering product marketing on the psychology of female consumers had already begun.

In the draft of his report, Lurelle Guild commented, “Times have changed and customers demand a change. The younger generation buys ‘impulse’ products to fit immediate needs. Tradition means little to them. Women are more color conscious now — especially in ensembling of colors in kitchens and baths. Acceptance of beauty colors ranks high. It is a must! There is a strong desire for other colors and it is our definite opinion that they should be included at once in your new product design. Without them, there will be a serious loss of business for you.” Once Guild had finalized his new design for Palmolive, he tested it with consumers in a nation-wide survey. Ironically, one of the comments that he chose to highlight in his report to Colgate-Palmolive was from Mrs. Minnie Link of Binghamton, NY, who wrote, “I have seen perfumes come and go— I suppose the same thing is true about soap. I like new things that are made better and prettier. They give me a lift in my old age.” (Courtney Asztalos)

The Lyall D. Squair Streetcar Advertisements Collection (Lyall D. Squair Streetcar Advertisements Collection), the Alvah Posen Papers (Alvah Posen Papers), the Egmont Arens Papers (Egmont Arens Papers), the Sylvia Carewe Papers (Sylvia Carewe Papers), and the Lurelle Guild Papers(Lurelle Guild Papers) are part of SCRC’s manuscript collections. The Crisis is part of SCRC’s rare books collection (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries).

Additional Sources:

Blount, Jim. “Washington, not Paris, dictated fashion during World War II with rationing and restrictions; U. S. military had more than 12 million wearing uniforms by 1945.” Historical Collection at the Lane. https://sites.google.com/a/lanepl.org/jbcols/home/2015-articles/washington-not-paris-dictated-fashion-during-world-war-ii-with-rationing-and-restrictions.

Edwards, C. (2016). Arens, Egmont (1889–1966). In The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design. London: Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472596178-BED-A074b

Hunter, Thomas. “The Prosperity Company Goes to War.” https://www.cnyhistory.org/wp-content/themes/oha/press/2015-03-25-BJ-Prosp.pdf.

Jr., E. L. (2004). Colgate Palmolive. In M. N. Lurie, & M. Mappen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. Credo Reference: https://login.libezproxy2.syr.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/rutgersnj/colgate_palmolive/0?institutionId=499.

“Lurelle Guild, FIDSA.” Industrial Designers Society of America. https://www.idsa.org/content/lurelle-guild-fidsa.

Madam C.J. Walker. (2020). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://academic-eb-com.libezproxy2.syr.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Madam-CJ-Walker/75942.

Savage, Woodson J., III. “Streetcar Advertising in America.” https://cld.bz/users/user-gMeEAad/Streetcar-Advertising-in-America/19#zoom=z.

“Soap Operas during the Golden Age of Radio.” Old Time Radio Catalog. https://www.otrcat.com/soap-operas-during-the-golden-age-of-radio.