Traces of a Movement

by Danny Sarmiento, Director of Administration & SCRC Curatorial Intern for the Plastics Collection

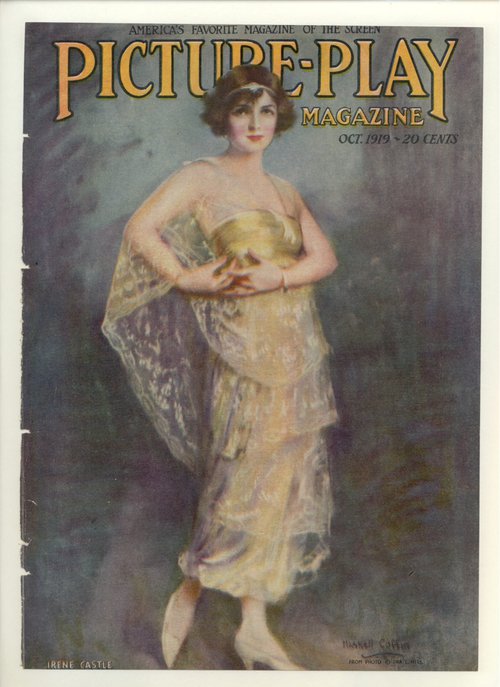

It’s possibly the most retold story about a haircut. One Connecticut newspaper headline read simply, ‘IRENE CASTLE CUTS HER HAIR.’” In 1914, as an internationally-recognized ballroom dancer, silent film star, and one of the first celebrities with an eponymous fashion line, Irene Castle was, in the truest sense, an influencer. Her newest look, the “Castle Bob,” caused something of a scandal and would later manifest in the short, fringed hairstyle made iconic by flappers in the 1920s. Today, Castle’s shorn locks reside in the Museum of the City of New York. The Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) holds its own piece of Irene Castle iconography in the below photograph and Picture-Play cover image of the star, part of SCRC’s Street and Smith Archive Serial Covers.

Irene Castle appears on the cover of Picture-play magazine in October of 1919.

The social and cultural implications of Castle’s dramatic chop were immediately remarked upon and debated in the press and public. Castle, herself, tossed off the remark, “I believe I am largely blamed for the homes wrecked and engagements broken because of clipped tresses,” in the Ladies Home Journal. And though this response can be read in the same tongue-in-cheek spirit as the “accusations” being levied at her, the very real impacts Castle’s haircut had are undeniable. In addition to the social commentaries that would emerge about femininity and gender in the years that followed, several more immediate effects were felt in the fashion and beauty industries. Business boomed as hair salons flooded with requests for bobbed hair, while the beauty supply market was met with a quite different reality – a story which is told, in part, through SCRC’s antique comb collection.

In an interview for the Antique Comb Collector’s Club, Alice Sawyer recalled, “The hairpin business died overnight in 1914 when Irene Castle cut her hair.” Sawyer had been working in Leominster, Massachusetts, a plastics manufacturing town responsible for two thirds of country’s comb supply and, within a few years of the infamous haircut, nearly half of the comb manufacturers in Leominster were forced to close. Although no one in the industry could have anticipated the influence that this singular act would have on their business, manufacturers of plastic beauty products were, by now, no strangers to major market disruptions of this scale. Only a few decades earlier, the introduction of cellulose nitrate (celluloid), opened many new possibilities for comb design and manufacture that had previously been constrained by materials less abundant and less versatile, such as wood, glass, rubber, various metals, porcelain, bone, and even papier-mâché.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, wooden combs were not as common as those made of other materials such as ivory, horn, and tortoise shell, but many examples from this era do survive. This particular example is undated.

Combs were occasionally made of multiple materials (horn and metal in this case) as a way to add to their decorative appeal.

Thanks to celluloid, decorative back combs and hairpins such as those picture below, could be manufactured in abundance, making them both more affordable and accessible to the general population. What was previously seen as a luxury item, available only to those of means was, by the late 19th century, mass-produced and made widely available. Susan Freinkel, writing on the history of celluloid combs suggests, “[P]lastics freed us from the confines of the natural world. [They] held out the promise of a new material and cultural democracy. The comb, the most ancient of personal accessories, enabled anyone to keep that promise close.” But if this was true, what are we to make of that closely-held promise when plastic combs were seemingly cast off into obsolescence not all too long after being brought to market?

Celluloid was widely used as a replacement for natural materials that were becoming scarce and expensive, into the late 1920s. One of the most successful applications was in the manufacture of celluloid dressing and decorative hair combs. This example is attached to the original salesman’s sample cloth.

An example of a celluloid hairpin that largely fell out of style the 1920s and 1930s when short hairstyles for women became fashionable.

When the advancing technology of plastic injection molding was introduced to comb manufacturing in the mid-nineteenth century, it became largely a single-material industry in a matter of just a few years. “Plastic,” according to Roland Barthes, “is the very idea of its infinite transformation […], less an object than the trace of a movement.” The traces left to us by the plastic comb, then, might be seen not as mere relics, but as markers on a path of continual transformation. And for Alice Sawyer, now running Diadem Manufacturing Company with her husband Lester, transformation was, indeed, a matter of her company’s survival. With the ornamental appeal of the comb waning, Sawyer would move on to develop several new comb designs aimed at the utility-minded consumer, introducing products such as the lifter comb, the hair trimming comb, and the “Grip-Tuth Hairtainer.”

Examples of the “Grip-Tuth Hairtainer,” manufactured in Leominster, Massachusetts by Alice and Lester Sawyer.

Meanwhile another comb manufacturer in Leominster would remake itself in quite a different way. In 1917 – a year when Irene Castle could be seen reenacting her legendary haircut in the film serial Patria – Sam Foster was contemplating the future of the plastic comb business he helped to build. Foster was a plastics man who, after failing to find his market with ideas that ranged from plastic jewelry, to dice, to “tiny birdcages that held plastic birds,” eventually settled into the more lucrative market for beauty products. And now, faced with a diminishing comb market and a group of concerned employees, Foster, unshaken, is said to have addressed his staff matter-of-factly: “So all right. We’ll make something else.” And so they did. Within a few years, the company would sell its first pair of plastic children’s sunglasses and, the business originally founded as Foster Manufacturing Company, was renamed Foster Grant. Under the new name, their product line expanded with the company’s first pair of adult sunglasses sold in 1929. By this time, Irene Castle’s fame had dimmed somewhat as the silent film era gave way to talking pictures and a new generation of celebrities. Bright lights on Hollywood film sets and the Southern California sunshine meant that many of the biggest film stars were seen (and photographed) in their sunglasses, priming Foster Grant to be part of the beauty supply market’s next Hollywood-fueled transformation.

Though manufactured several decades later, these children’s frames recall the very first pair of sunglasses sold by Foster Grant in the late 1920s.

The Plastics Artifacts Collection and the Foster Grant Collection held by the Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center are bound together both by their physical material and by the material culture of which they are a product. These collections represent markers in the development of plastics design and manufacturing and allow us to trace, at least in part, 20thcentury conceptions of beauty, fashion, and celebrity, as embodied by the likes of Irene Castle and those that came after her.

The Plastics Artifacts Collection (Plastics Artifacts Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and the Foster Grant Collection (Foster Grant Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections. The Street and Smith Archive Serial Covers (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and Antique Comb Collector’s Club newsletters (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of SCRC’s rare books collection.

Additional Sources:

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. 1957.” Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang (1972): 302-06.

Castle, Irene. “I bobbed my hair and then—.“ The Ladies Home Journal, October (1921): 124.

Denise N. Green, Denise N. “The best known and best dressed woman in America: Irene Castle and silent film style.” Dress 43.2 (2017): 77-98.

Felix, Rebecca. Sunglasses success. Abdo Publishing, 2018.

Freinkel, Susan. Plastic: a toxic love story. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Kittler, Glenn D. More than meets the eye: the foster grant story. Coronet Books, 1972.