What Then Shall We Say About Croton?: Attempts to Integrate Syracuse City Schools

by Dane Flansburgh, Assistant Archivist

From August 2016 to January 2018, I processed the records of the Crusade for Opportunity (CFO), an anti-poverty organization based in Syracuse, NY, that existed during the 1960s. In the two and a half years since I finished processing the CFO records, the increasing widespread swell of support for the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, among others, has thrown the archival work I did in sharp relief. Although police brutality and unfair justice systems has been the focus of the BLM movement, issues such as segregated schools are concerns as well. We frequently think of segregated school districts as a problem specific to the 1960s, but inequitable education and employment opportunities for Black communities persist to this day. As a parent of four children in the Syracuse City School District, disparities in educational opportunities are often at the forefront of my mind. With New York State leading the nation with the most segregated public schools in the country, it is clear that work still needs to be done.

The Crusade for Opportunity organization was founded in 1964 with the desire to solve generational poverty based on racial discrimination. Widespread discrimination existed when it came to housing, education, and employment opportunities for marginalized communities, and the organization believed that these racial discriminations were barriers to opportunity, and, ultimately, success. According to an internal CFO report, the organization had a mission to “pinpoint the deficiencies of the social structure and system” and “assist the economically oppressed and socially disadvantaged groups so that they will be free of oppression…and demonstrate new approaches to the society at large in order to accelerate the social change.”[1] In order for Black communities to succeed, the organization believed, systematic racism had to end.

The CFO took a three-prong approach to create opportunity: community service, employment training, and education programs. For community service, the organization established community centers where members of the community could congregate and plan. For employment, they offered skill training programs and Neighborhood Youth Corps, a job program that connected teens with employers based on their skill sets. And finally, the organization offered education programs, such as the first Head Start program (early childhood education centers) in the nation, tutors for struggling students, and field trips.

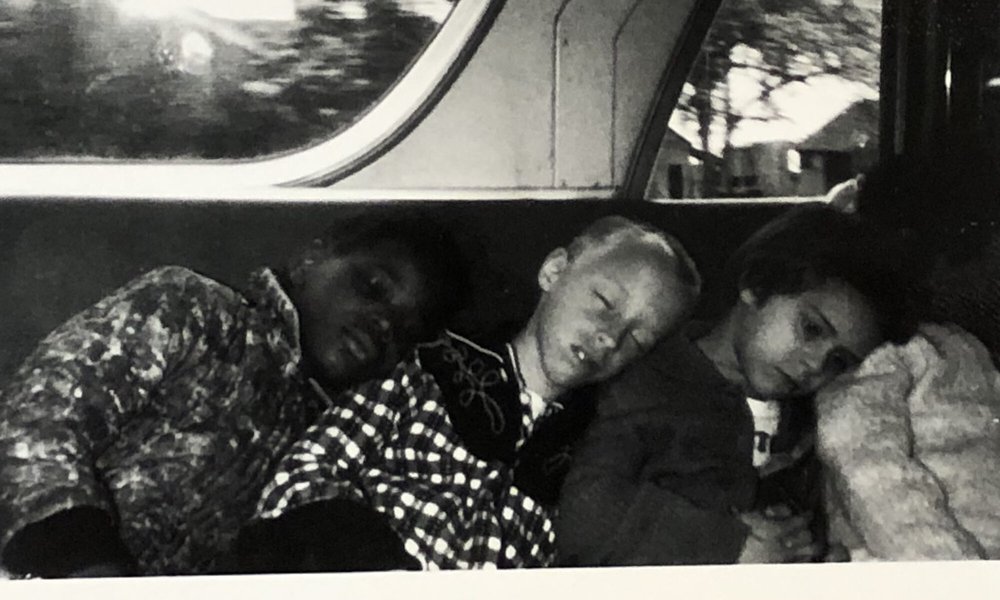

As part of an education initiative, Crusade for Opportunity regularly offered field trips for children in Syracuse neighborhoods. Here are four children sleeping on a bus after a CFO field trip to a local farm.

Yet, in terms of education, the organization was limited in its capacity to combat the complex reality of segregated schools in Syracuse. Although de jure segregation – segregation by law – had been established as unlawful by the Supreme Court in 1954, de facto segregation – segregation established by segregated neighborhoods – was as much of an issue in the north a decade later. For example: In 1964, Croton Elementary School in Syracuse was 90 percent Black, while Ed Smith Elementary, another school in the district, was 92 percent white.

The CFO was invested in understanding how segregated schools affected their constituents. The organization’s research department explored issues relating to housing, criminal justice, employment, and education. The research CFO conducted regarding education suggested that disparities in predominately Black schools, such as lack of funding, access to resources, and community support, resulted in an imbalance in quality of education for Black children compared to their white counterparts. The Syracuse Committee for Integrated Education, a committee led by CFO researcher Hilda Rosenfeld, found that academic testing in Syracuse revealed that students in majority Black schools tested below grade level, whereas students in majority white schools tested above average. Dropout rates in the city were over 40 percent in poor, majority Black schools, compared to just 4 percent in affluent, majority white schools. “If segregated Southern schools have been ruled inferior and less than equal,” the report authors concluded, “what then shall we say about Croton?”[2]

In September 1965, Syracuse School Superintendent Franklyn S. Barry, under pressure from local agencies and organizations like the CFO, closed two predominately Black schools (Madison Junior High School and Washington Irving) and began to integrate those students into white schools. Croton Elementary, however, remained open – the superintendent feared that he had no location to reassign its 1,200 students. Beginning in the fall of 1965, 900 Black students were bused to previously white majority schools. Fearing backlash from white parents, children from predominately white schools were not sent to predominately Black schools. In addition, the superintendent allowed open enrollment for all their schools within the district, so that Black parents had the opportunity to send their child to a preferred school. A year later, Superintendent Barry reported promising results: “24 children who were bused…achieved a total of 9.2 months progress in reading (in 8 months) while their matched counterparts (in the predominately Negro school) did in 4 months.”[3]

Integration, however, was about more than just academics – it was also about the breakdown of barriers between different racial and ethnic groups. School integration not only gives students the opportunity to learn from those with different backgrounds and experiences, it also promotes shared experiences for students in a single environment. Integration itself is a form of education.

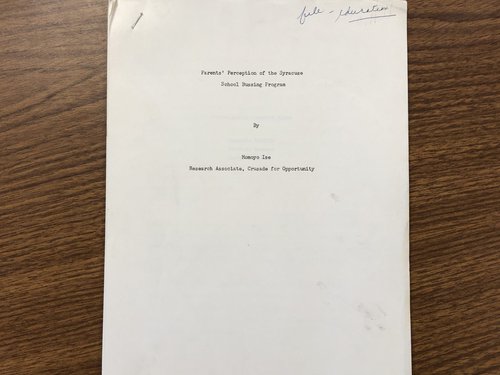

In 1966, the CFO research department publicly released their findings of a survey they conducted regarding Black parents’ perceptions of busing their children to predominately white schools. Seen here is the cover page of that survey.

During the spring of 1966, the CFO research department sent out research aides into Black neighborhoods in Syracuse to gauge the perceptions amongst parents regarding busing and integration. Their interviews with the parents revealed that although parents were unhappy with the longer bus times and, consequently, earlier start times in the day, most parents were happy with both their children’s academic and social progress. For example, 53 percent of parents believed that their child received a better education compared to their prior school, and 61 percent of parents thought the new school was “very good.” Additionally, 76 percent of parents said that their children liked their new classmates “better or to the same degree as their old classmates.”[4]

Ultimately, school integration did not last, at least in Syracuse. There are many factors for this. Chief among them is the continued white flight to the suburbs and white parents’ objections to send their children to majority Black schools. A number of Syracuse schools continued, and continue today, as de facto segregated schools, Croton Elementary (now Dr. King Elementary) among them. It has also been more than 50 years since Crusade for Opportunity closed its doors. The organization struggled as more community members became engaged with daily operations, sparking internal struggles between the members and the administrators. Additionally, external tensions emerged between the organization and local power structure when CFO members pushed for more social change. In 1967, after a short three-year run, CFO lost its funding. Yet their goals of ending systematic racism and providing opportunity for all is still an unrealized one. The failed attempts to prevent the continuance of de facto segregation in schools is a reminder of that.

The images featured in this post are from our Crusade for Opportunity Records (Crusade for Opportunity Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

[1] Moko Ise, “Comments on Report of the Community Problems Study Committee,” February 1967, Education reports, Box 261, Crusade for Opportunity Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University.

[2] Hilda L. Rosenfeld, Joyce I. Ross, Mitzi O. Cooper, “Education and Integration in Syracuse,” Event: A Journal of Public Affairs, Vol. 7, no. 1 (Fall 1966): 8-14.

[3] “Process of Change: The Story of School Desegregation in Syracuse, New York,” Commission on Civil Rights (June 1968): 10.

[4] Momoyo Ise, “Parents Perception of the Syracuse School Bussing Program,” Box 262, Crusade for Opportunity Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.