Jack Nelson: On the Art of Watching People Who Use Machines Exhibit

Page featured image content

Page main body content

Jack Nelson is an artist whose work defies easy classification. Born in Chicago, Illinois in 1929 and primarily active in the 1960s through the 1970s, he explored the metaphysical aspects of religion and nature through sculptures, drawings, collages, and video art. His work shows similarities to the contemptuous Fluxus and Pop movements but displays humanistic tendencies often lacking in his conceptual peers.

After graduating from the Arts Institute of Chicago, Nelson relocated to Sweden where he lived through the mid-1960s. Upon returning to the United States, he created machine-like sculptures of wood and metal but by 1963 he had abandoned what he deemed his ‘heavy’ pieces, stating that he had become “bored with machines – bored with heavy aesthetics. [I was] Interested more in people who use the machines.” The last major work in this vein was made in 1967, a complex automata created for an urban renewal project in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Unable to abandon machines completely, he created increasingly delicate sculptures of wood and metal through the mid-1970s.

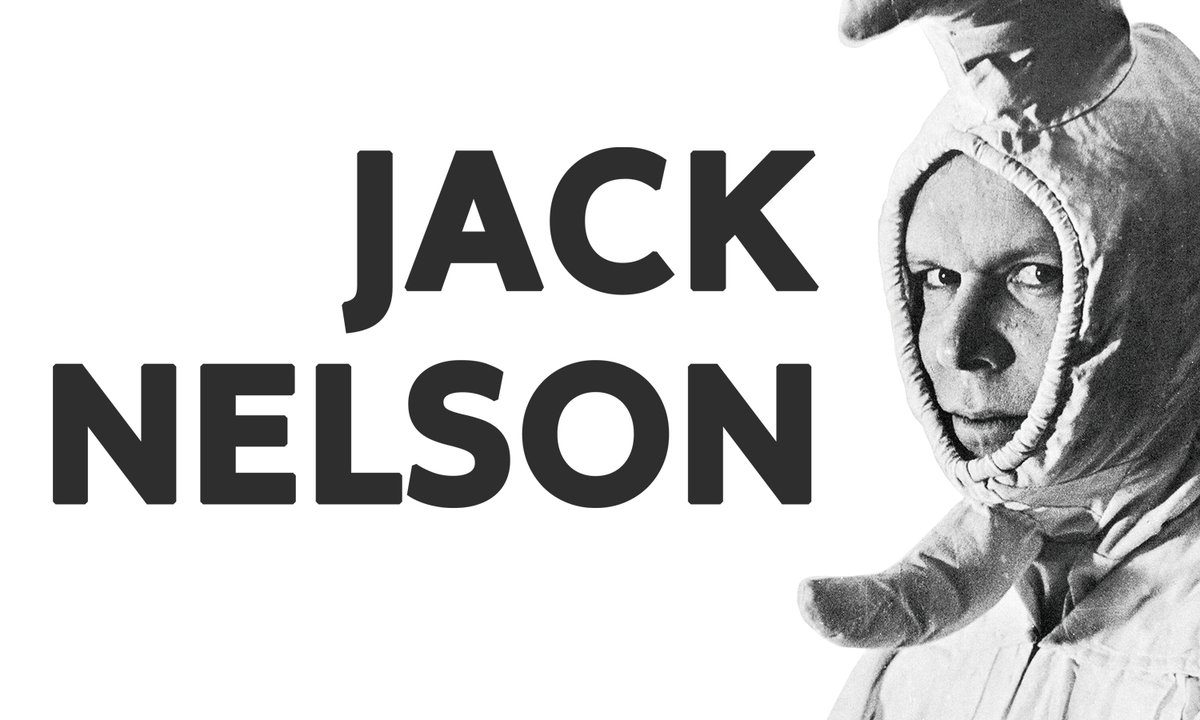

Perhaps Nelson’s best-known works are the Moon People, also known as ‘the people who use machines’. These mostly figural sculptures are totem-like assemblages, constructed of plaster, muslin, vacuum formed plastic, and found objects. He worked closely with his partner Jeri Nelson (1935-2016) , a gifted tailor who crafted many of the more complex fabric elements in his sculptures. His iconic alter ego, the Moon Man, saw the artist clothed in muslin and wearing an open-face mask, a persona he considered a transcendental spiritual identity. The sociable Nelson would don costumes that mirrored his sculptures, another facet of his art-as-experience aesthetic, and one that would come into play with his video work.

In 1966 the couple relocated to upstate New York where Nelson took a position as an associate professor in the School of Art at Syracuse University, helping to create its Department of Experimental Studios. Artists, including a young Bill Viola, were encouraged by Nelson to explore the fledgling video medium.

Religion was a theme that permeated Nelson’s career, a result of growing up in a strict Lutheran Fundamentalist family. He would incorporate Christian iconography such crosses and grails, often to express his distrust of organized religion.

Nelson had a life-long love of nature, best illustrated in his drawings and collage work. Creatures of the land, water, and air are presented in an anthropomorphized manner. His collages of the 1980s can be seen as tributes to both Dada and Pop Art.

Perhaps the artist’s most enduring legacy will prove to be the impact he had on his students, sharing a vision of playful irreverence and in the process inspiring the next generation to greatness.