Collection Spotlight: Grove Press

by Ann Skiold, Librarian for Visual Arts and Danny Sarmiento, Curator, 20th Century to Present

Barney Rosset wrote in his autobiography, “Rosset, My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship,” that “rebellion runs in my family blood.” He was the only child of Jewish and Irish Catholic parents. A mediocre, directionless student from Chicago, he served as an Army photographer in India and China, bringing along two books, Edgar Snow’s “Red Star Over China” and Andre Malraux’s “Man’s Fate.”

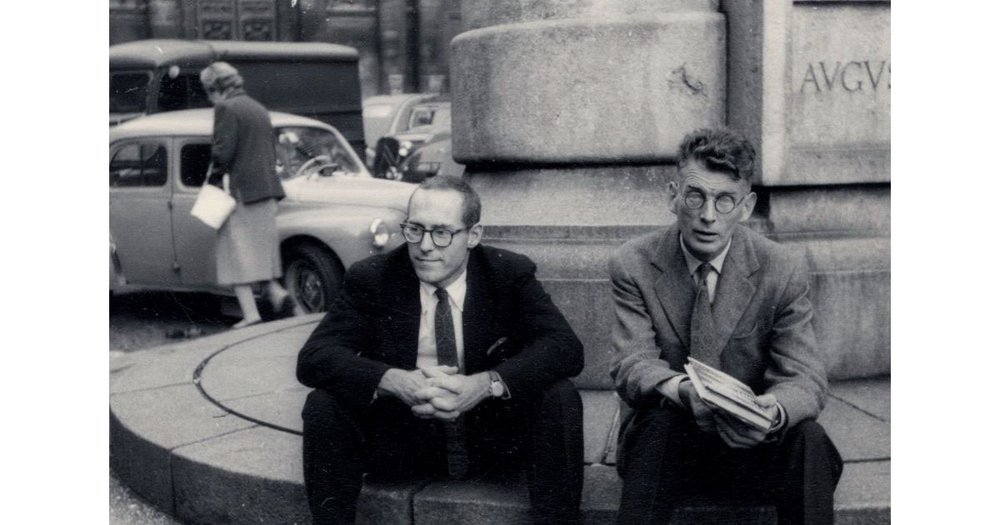

At the urging of his wife, the abstract expressionist artist Joan Mitchell, Rosset bought Grove Press in 1951 for $3,000 he had borrowed from his father. Leaving behind his early passion for film, Rosset followed Mitchell to Paris and began pursuing little-known authors such as the reclusive Samuel Becket after whom he would name one of his sons. He obtained the right to publish “Waiting for Godot” in America. Books such as D.H. Lawrence’s unabridged version of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer” and William Burrough’s “Naked Lunch” were banned in the United States due to their sexually explicit content. Rosset went to court arguing both against censorship and for the literary value of these works. His court victories allowed Americans to read these hitherto fore banned books.

Barney Rosset hired Richard Seaver as editor, publisher and translator. Seaver had graduated from the Sorbonne and helped Grove Press connect with reclusive French authors. Seaver recounts his life in publishing in his autobiography, “The Tender Hour of Twilight.” The Grove Press periodical, Evergreen Press (published 1957-1973), published works by Che Guevara and Malcolm X, resulting in bomb threats and one actual bombing in the summer of 1968 when a grenade exploded in Grove Press offices. Thankfully, no one was injured. Barney Rosset was not deterred by the bombing and continued to publish books, release films and articles, many of which were challenged in court under the First Amendment (freedom of speech).

Rosset was not a good businessperson and eventually had to sell Grove Press to the oil heir Ann Getty in 1985. Despite the promise he could remain in charge, Getty fired him a year later. Barney Rosset died in February 2012, and the New York Times obituary read “Barney Rosset Dies at 89, Defied Censors, Making Racy a Literary Staple”.

Rosset’s memory lives on, in part, through the Grove Press Records which are held at the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) at Syracuse University Library. With an initial gift of archival materials in the early 1960s, Rosset and Grove Press continued to send items to SCRC until Grove was sold in 1985. Some 600 linear feet of material have been processed and made available to researchers, providing an intimate look at one of America’s most infamous publishing houses. In 2013, SCRC mounted a major exhibition that highlighted Grove’s influence on the American literary scene and political climate, a legacy which endures to this day. With book bans, censorship and other challenges to free expression still very much in our public discourse, the Grove Press Records help tell a complicated story, not of a single man or publisher, but of a movement in a long tradition of liberation-minded cultural production.

To provide feedback or suggest a title to add to the collection, please complete the Resource Feedback Form.