Accessibility and Discoverability: Describing Street and Smith Cover Art

by Natasha Bishop, Reference Assistant

This summer, I have been working for the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) from my dining room table. While working remotely comes with its challenges, it has also presented the SCRC team with opportunities to embark on meaningful digital projects. For example, as part of an ongoing effort to increase the accessibility of our collections, we are writing accessible descriptions for SCRC’s collection of Street & Smith dime novel covers.

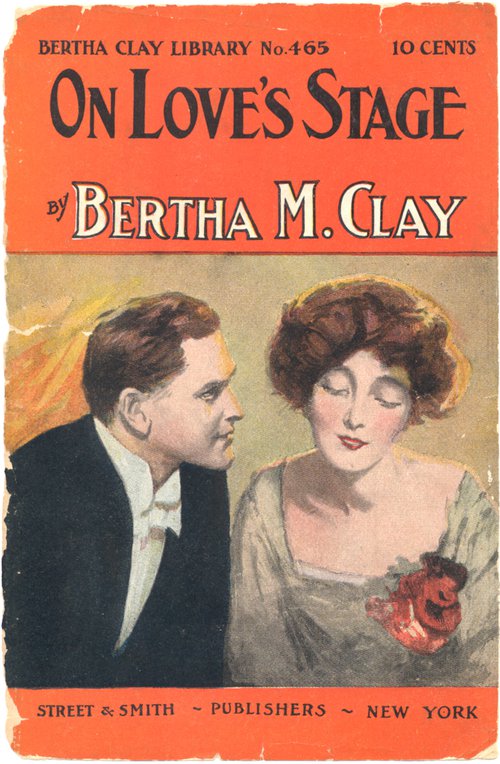

Cover of the 1895/1915 Street & Smith dime novel On love’s stage, or, Behind the heart’s curtain (Bertha Clay Library no. 465). Rare books, Special Collections Research Center.

Founded in 1855, Street & Smith was the largest publisher of pulp fiction and dime novels in the United States of its time. The prolific publishing house was a “fiction factory” that produced juvenile book series, fashion magazines, comics, and dime novels. The company had a clear vision for their publications and, under this model, the publishing editors set strict restrictions on the style of writing and cover art produced by the company. Over time, Street & Smith shrank its line of pulp titles before abandoning the genre entirely in 1949. The Street & Smith dime novel cover collection is the second collection for which the SCRC team has written accessible descriptions. This collection was selected to be visually described because of Street & Smith’s importance in the history of United States publishing, the dime novels’ rich representation of American popular culture, and because over 1,700 of these covers are now digitized and available at SCRC’s Special Collections Online. Scanned images of these covers were microfilmed as part of a 1995 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) funded project to preserve and catalogue SCRC’s Street & Smith collection.

Simply stated, accessible descriptions are a descriptive summary that accompanies an image. Accessible descriptions go beyond standard image captioning by describing the actual content of the visual material. Providing images with accessible descriptions ensures that they are accessible to researchers with visual impairments who rely on screen readers. This is because visual descriptions can be read by screen readers, thereby providing the same meaning and non-text content as its visual counterpart. These descriptions can also serve to protect fragile archival materials from excessive handling. When looking through the visual material of a collection, a researcher may have to handle much of it to find what they are looking for. By making visual descriptions of this material available online, researchers are able to begin narrowing down their search before accessing the collection on-site. This reduces the overall amount of material they must handle in order to access what they need, which ultimately helps preserve the state of the collection.

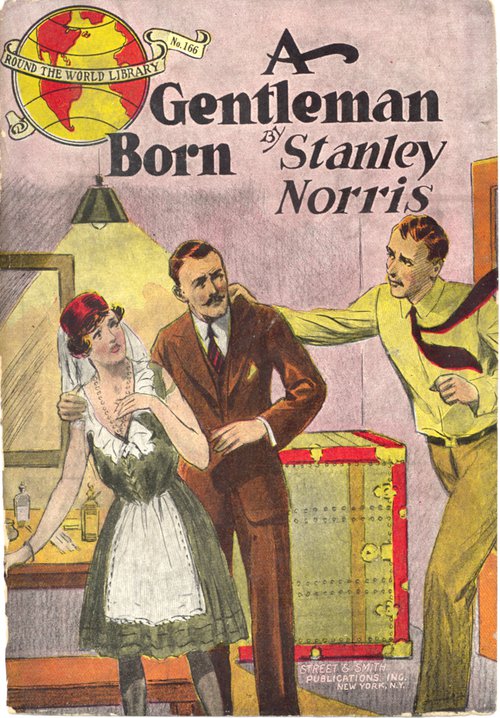

Cover of the 1900 Street & Smith dime novel A Gentleman Born (Round the World Library no. 166). Rare books, Special Collections Research Center.

I found writing accessible descriptions to be deceptively difficult because every visual description should increase both accessibility and discoverability of the image it describes. In order to accomplish these two goals, the information must be presented consistently, clearly, and concisely. Consistent terminology increases image discovery by ensuring the text can be indexed and searched. In order to be accessible to researchers with visual impairments, however, the description must be thorough enough to transmit the same content as the image. Finally, the description must avoid bias and interpretation to present an objective reading of the image. Take, for example, the 1900 Street & Smith dime novel cover, A Gentleman Born (Round the World Library no. 166). While the man in the yellow shirt appears to me to be rushing into the scene and threatening the other two figures, this is an interpretation of the scene rather than an objective analysis. A more neutral presentation of this material is:

“A man in a yellow shirt strides toward the two figures in the center of the cover, placing his right hand on the man’s left shoulder. The central figures look up and over their shoulders as if startled by the man’s presence.”

This description removes my reading of the scene as threatening, thereby allowing the reader of the text to form their own interpretation.

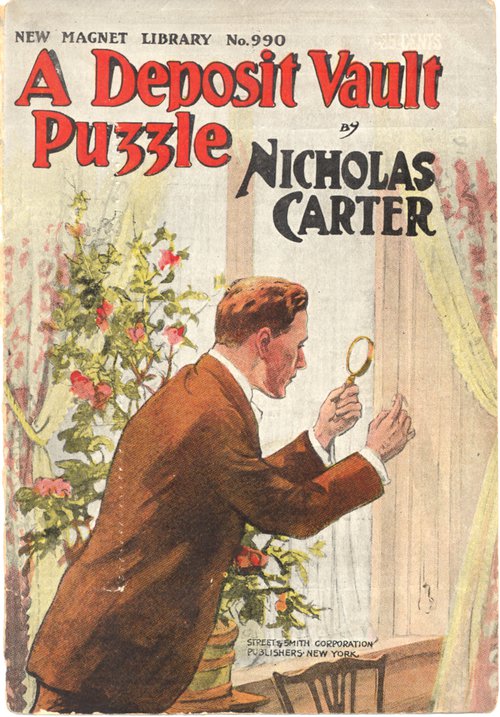

Cover of the 1895/1915 Street & Smith dime novel A deposit vault puzzle, or, The contents of box A, no 39 (New Magnet Library no. 990). Rare books, Special Collections Research Center.

Having just received my master’s degree in Art History from Syracuse University, I have found working on this accessible description project both fun and rewarding. Art historians must be able to accurately describe visual artworks, and this is a skill we spend years cultivating. The Street & Smith visual description project has allowed me to utilize this skill in a meaningful way by making SCRC materials accessible to more individuals. As someone who advocates for far-reaching accessibility in academic spaces, I am encouraged by the increasing presence of accessible descriptions and hope it becomes a standard companion to visual archival materials.

The Street & Smith dime novels are part of SCRC’s rare books collection (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries). The Street & Smith Records (Street & Smith Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) and Street & Smith Collection (Street & Smith Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of the Special Collections Research Center’s manuscript collections.

Additional Source:

Describing Visual Resources Toolkit: Describing Visual Resources for Accessibility in Arts & Humanities Publications, University of Michigan Library, https://describingvisualresources.org.

This post has been updated on 7/8/2020 to reflect the terminology used in the Street & Smith metadata project, changing ‘alt-text descriptions’ to ‘accessible descriptions.’ Thanks to Deirdre Joyce for the correction!