Behind the Spine

by Jessica Rice, Preservation Lab Supervisor

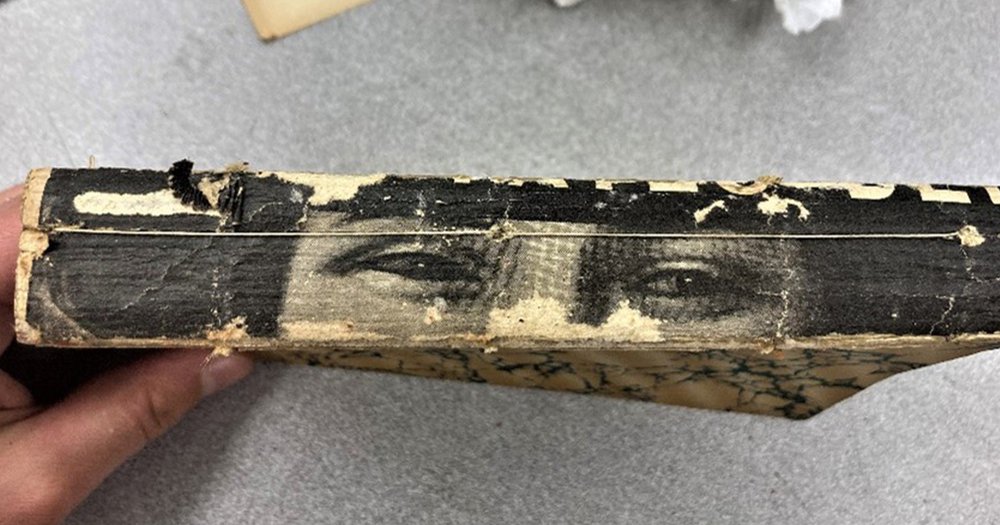

You are relaxing with some tea and reading a book, and suddenly you get the distinct and eerie feeling that eyes are watching you. You do not see anyone else in the room. Well, just an idea: those eyes might be inside your book!

Employees in the Syracuse University Preservation Department take pride knowing that their work will impact readers for years to come. The repairs vary from simply re-attaching loose pages to reinforcing the book’s structure. Occasionally, however, the books themselves provide little surprises that add fun to the process.

Many older books have a paper or cardboard lining inside the spine of the book. (The spine is the “back” part of the book, opposite from where the pages open.) Bookbinders would put a lining in to help the book open more easily. For the most part, the linings are just dull scraps of blank paper, perhaps something that was found lying around the workshop.

But every once in a while, we find a spine lining that provides an extra dimension to the book considered as an object. What was the binder of the book-with-eyes thinking? Perhaps they were making a (really inside) joke, providing personal commentary on the book’s topic, or even just amusing themselves on a dreary day. As with all the linings discussed here, the paper was later removed to complete the repair and was not preserved.

You just never know what you might find inside a book once you take it apart. The spine liner below was found inside a 1950s-era book on Rationalism in French Literature of the 1700s.

The publisher was J. Vrin, located in Paris. Did the binder pick this paper on purpose, perhaps as a comment on rationalist criticisms of social institutions? The grumpy-looking woman in the center certainly looks as if she might have something to say. Or, more prosaically, this was just a random left-over scrap from an advertisement or magazine page.

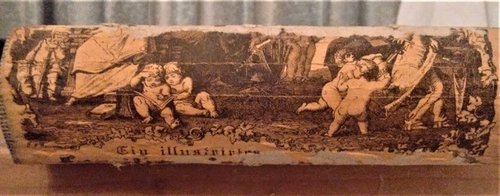

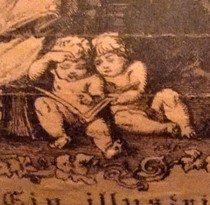

This book’s spine liner does not look like a randomly cut piece of paper, but something that was selected to allow the two groups of cherubs to remain intact. As you can see in the close-up, the two little cherubs are enjoying a book. The paper scrap shows just a portion of what originally was a very detailed illustration with fine cross-hatching, a lovely floral border, and a dramatic scene on the right side that is difficult to decipher. This kind of find makes one wish to see what the rest of the image contained.

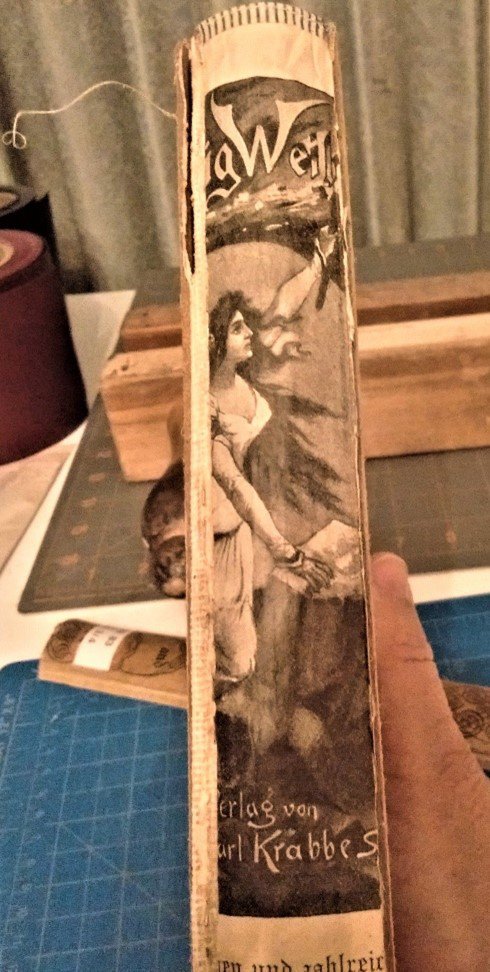

Below is another rather dramatic image, with a woman holding something in her left hand that could possibly be a torch. The partial text at the bottom, “Verlag von Carl Krabbe,” is the name of a publishing company in Stuttgart, Germany. This spine lining may have started off as a portion of a book cover or catalog from that publisher.

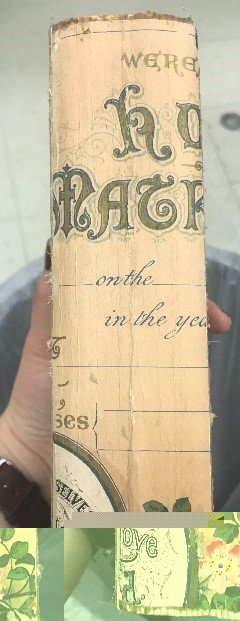

Below is a spine liner made from what appears to be a form or page related to marriage. The larger letters at the top look like the beginning of Holy Matrimony. In the middle of this scrap paper are spaces for the date and what might be a space for witnesses to sign.

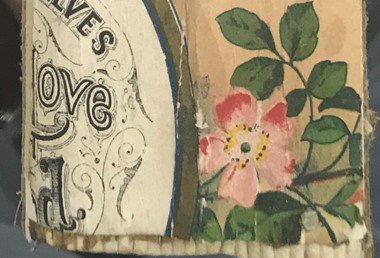

Below, a closeup view of the bottom of the paper shows a delicate flower image that appears to be a wild rose along with the word “Love” in ornate script.

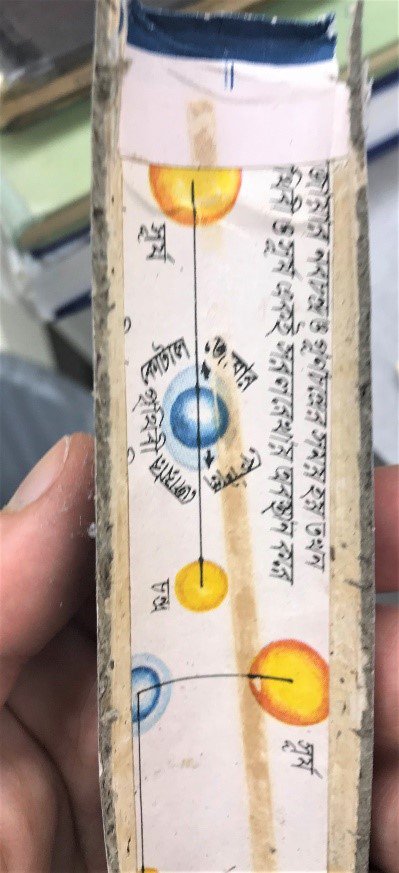

Finally, sometimes we see text written in a language that we cannot read on the spine lining of a book. There can still be an interesting picture that draws attention. In this case, the yellow and blue circles bring an astronomical diagram to mind.

These humble and hidden scraps of paper are amusing and give some insight into the world of bookbinding in the past. A physical book truly links a past craftsperson and a current reader in a real and tangible manner. While there are still people who make books by hand, most books now are printed and bound on large industrial machines. Book designers are not as intimately involved with the final products. Even today, however, people make creative choices about fonts, book covers, illustrations, sizes, and materials. That human element of the book, so apparent as we work in Preservation, remains and will continue to make books a valuable part of the cultural record.