Printing the Middle Ages: A Renaissance Edition of Bernard of Clairvaux

by Sebastian Modrow, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

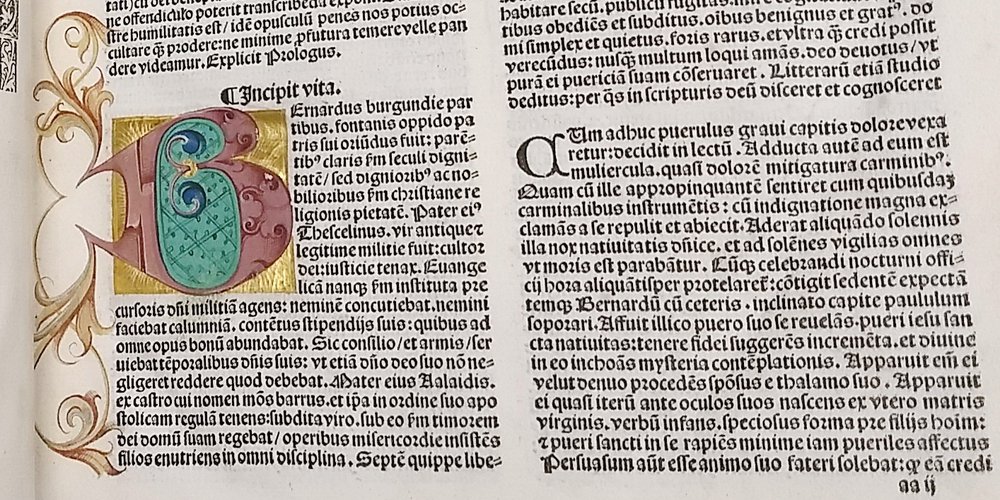

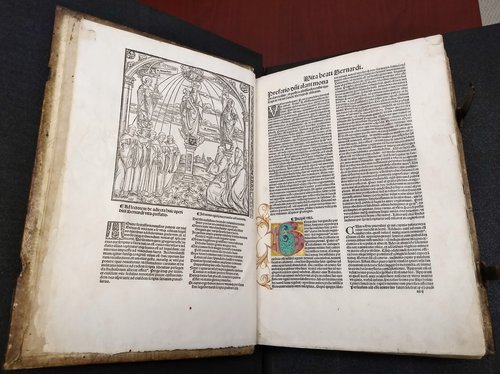

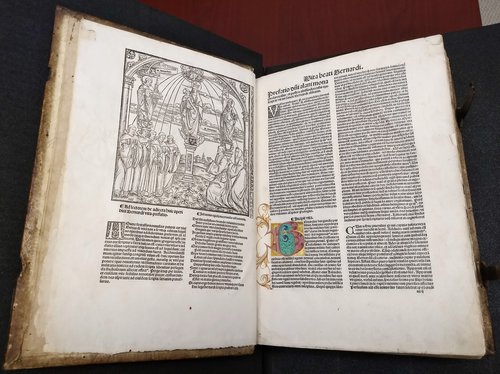

Verso of the title page with large woodcut and beginning of the Vita of St. Bernard on the opposite page featuring the only illumination of the copy.

In early 2019, SCRC acquired a Renaissance edition of the works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Printed in 1508 in Paris by Jehan Petit, it was later illuminated and apparently put to good use as indicated by its frequent marginalia. It also came in a contemporary pigskin binding. The chosen author of Petit’s 1508 edition, Bernard of Clairvaux, probably doesn’t make anyone’s top 10 associations list when it comes to the Renaissance, as he was, in fact, neither a classical author nor a Renaissance mind, but instead, one of the most influential spiritual leaders of the Middle Ages. Knowing this, you might question why a French Renaissance publisher would bother to publish his works. Like other contemporary publishers, and following in the footsteps of Gutenberg’s printing of the Bible, Petit chose religious subject matter for his printing, a subject popular among monastic and scholarly settings alike. So, who is this Bernard and why should we care about him?

The Man and His Works

Bernard of Clairvaux was born in 1090 into an aristocratic family in the Dijon region of Burgundy (France). He was to become one of the most influential leaders during the High Middle Ages, not only of the young Cistercian Order, but of the Catholic Church in general.

After the death of his mother in 1107, Bernard sought the counsel of Stephen Harding, abbot of Cîteaux Abbey, establishing a relationship that would ultimately lead Bernard to abandon his literary studies and ecclesiastical career and to join the monastery in 1112. This monastery had been established only a few years prior in 1098 by Robert of Molesme in the ‘Burgundian wilderness’ in an attempt to reform and re-focus the Benedictine order on the spiritual life in imitation of Christ. Instead of reforming the old order, however, the movement led to a split with the Benedictines, and Cîteaux emerged as the mother house of a new order, named accordingly, the Cistercians.

From 1112-1115, Bernard immersed and distinguished himself in theology and and explored his own spirituality, developing a leadership potential that Abbot Harding recognized and acknowledged with the mission to lead a small group of Cistercians to found a daughter house at Clairvaux, situated in the border region of Burgundy and Champagne. In the years following the founding of the house at Clairvaux, and forced, in part, by his deteriorating health, Bernard retired to a small hut, which gave him the time to not only focus on his spirituality, but also to produce his first writings, such as his “Praises of the Virgin Mother.”

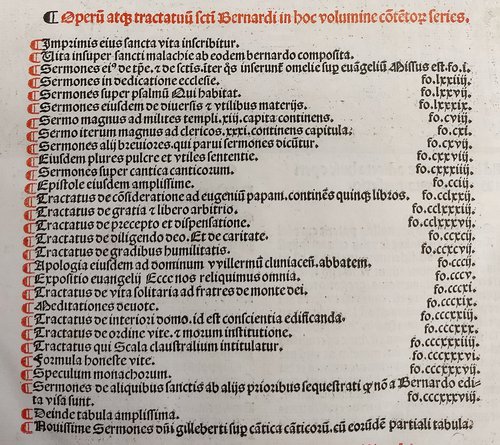

The edition’s table of contents as found on the title page.

Writing became a way for Bernard to contemplate, in solitude, God’s great mysteries and then to share his experiences and insights with the world. This attests to his over 300 letters and sermons, many of which center around the imitatio Christi (the imitation of Christ). Not all of his writings, however, were of a contemplative nature. With his Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae(“Book addressed at the Knights Templar on the Praise of the New Knighthood,” written between 1120-1136), Bernard directly entered the debate about the justification of the existence of warrior-monks where he positioned himself in the affirmative.

Bernard was also one of the most prominent promoters of the disastrous Second Crusade (1147–49), which illustrates that as much as he liked to withdraw from the world and contemplate God’s mysteries, he found himself instead at the center of the events of his age. Five popes relied on his counsel, church- and other councils invited him as mitigator and as a representative of the old contemplative approach to the holy scriptures, as reflected in probably his most famous work, his “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles.” Bernard grew increasingly weary of the rise of Scholasticism as it developed at Europe’s cathedral schools and its rationalizing approaches to Christian doctrines.

He must have, indeed, been a person of great charisma and great oratorical skills, a fact that is also reflected in his writings and that would earn him the title doctor mellifluous, because his instructions to the faithful were always ‘flowing sweet as honey.’ Bernard was canonized on January 18, 1174.

Despite the prevalence of scholastic texts during the High and Late Middle Ages, Bernard’s spiritual message maintained its appeal inside and outside the Cistercian order. He is, for example, the final guide for the protagonist of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and it is at his intercession with the Virgin Mary that the true nature of God is revealed to Dante’s protagonist. The Renaissance scholar, Erasmus of Rotterdam, in his The Art of Preaching, praised the charming and lively eloquence of Bernard’s style, so it should be no surprise that his works were printed throughout the Renaissance. To one of these editions we want to turn now.

The Publisher and his edition

Our book in question is based on the edition of Bernard’s works by André Bocard and was printed by Jehan Petit (c. 1470-1530). Petit was one of the key players of the French book trade during the transition from the Incunabula Period into the 16th century and one of the four official stationers of the University of Paris. Petit’s business would develop into a large-scale publishing enterprise, contracting multiple printers at the same time for his projects. Over the span of his career (1493-1530), this amounted to over 1,000 different volumes, many of which were – unsurprisingly, for an official university bookseller – mainly of scholarly interest and mostly in Latin. He published our Bernard of Clairvaux edition in Paris on March 31, 1508.

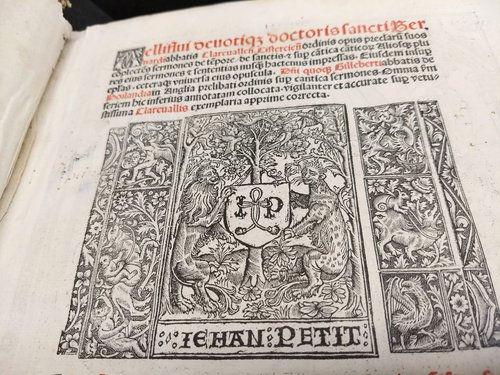

ehan Petit‘s printer’s device on the edition’s title page.

Petit’s opulent but elegant printer’s device connects the publication with his workshop. Half a century after Gutenberg’s first Bible edition, the printed book had come a long way. Still, we can detect reminiscences of the medieval manuscript tradition of which Paris was one of the most productive centers: The elaborate so-called gothic type face evokes the ‘feel’ of the handwritten book as do the illuminated and woodcut initials. However, as seen with the printer’s device, the use of woodcuts is not limited to initials.

Verso of the title page with large woodcut and beginning of the Vita of St. Bernard on the opposite page featuring the only illumination of the copy.

When turning the title page, the reader will in fact encounter the most impressive woodcut illustration in our Bernard edition showing the Virgin and Child flanked by St. Bernard and St. Malachy (see below).

The Book

Front cover of SCRC’s Bernard copy showing its blind-stamped pigskin binding and its brass ‘furniture’.

SCRC’s copy contains a total of 456 leaves and measures 38.5 x 26 cm (15” x 10 1/8”). It is bound in beveled wooden boards wrapped in blind-stamped pigskin (‘blind’ meaning the impression is not colored), consisting of various lines and floral motives. Brass corner guards and brass bosses (metal studs) lend extra protection to the cover. Bookbinders and conservators usually refer to these protective elements as book ‘furniture.’

The book’s fore-edge with brass clasps and leather tabs.

The book is held together by two brass fore-edge clasps. Leather tabs on the copy’s fore-edge marking the beginning of Bernard’s individual works within the edition, as well as marginalia in contemporary hand, attest to the frequent use and systematic study of our copy during the late Renaissance period.

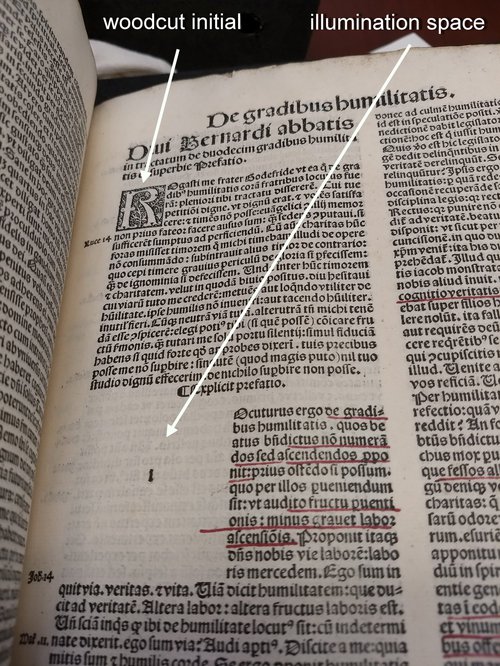

First page of Bernard’s De gradibus humilitatis with woodcut initial and blank illumination space with the required initial in the center.

This early 16th century edition of Bernard’s works is a perfect example of the longevity of the medieval manuscript tradition in the history of the early printed book: While Petit executed many initials as woodcuts, he decided to also leave space for illuminations on the first page of each of Bernard’s major works in this edition, indicating the required initial with a small letter in the center of the gap.

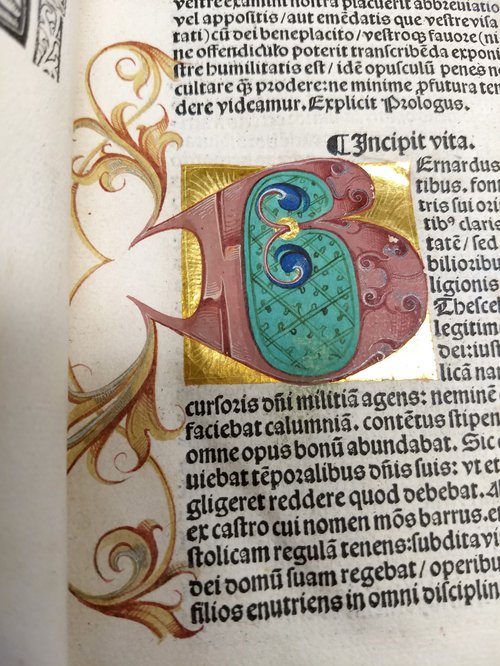

The only executed initial of SCRC’s copy at the beginning of Bernard’s vita.

Only one of the many potential initial illuminations is executed in our copy, but it is an important one: It appears at the beginning of the copy on the first recto after the title page. It is embedded into the vita of St. Bernard of Clairvaux that precedes this collection of his works. The illumination in question represents a very elaborate “B” extending over eleven lines which, in this position, is the initial letter of the word “Bernardus,” the subject of the vita and author of the works edited in this volume.

The Largest Book Worm in the History of the Book?

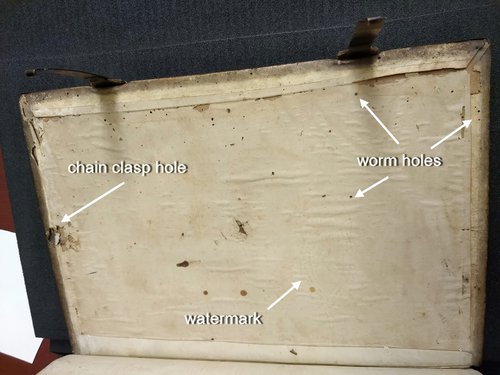

The close study of a rare book reveals information not only about its maker and their edition of a book, but also about its use and place in a collection. Parts of the cover boards and the text block of our copy are perforated with holes, bearing witness to the fact that there are two kinds of book worms – the metaphorical and the real ones. Two of these holes, however, clearly stand out due to their large size and position right in the middle of the top part of the back board. On the outside of the binding, they are also enclosed by a brown circle that makes them stand out even more.

The large double hole in the backboard as seen on the outside of the binding.

The double hole and its brown circle are likely remnants of a chain clasp that was once attached to the book’s cover for security purposes. In a world without electromagnetic library security systems, medieval and early modern librarians found other ways to prevent the theft of the objects in their care, objects we have to keep in mind, that even in their own days, represented items of considerable monetary value.

nside of back cover showing wormholes, the chain clasp hole and the watermark of the pastedown or lining paper.

This attachment combined with the book’s content, suggests a monastic or university context (the publisher was one of the official stationers of the University of Paris!). During the medieval period, books were first chained to reading desks, known as lecterns, and – as collections and storage facilities evolved – later also to bookshelves, this was a practice that continued into the early modern period. One of the few preserved ‘chained libraries’ can be found in England at Hereford Cathedral. It should be noted, however, that Hereford’s books are stored with the fore-edge facing outwards and the chain clasp attached to the long side of the cover board. How to account, then, for the position of the clasp hole on our Renaissance edition? The simplest answer seems to be that our book was stored differently, bringing us back to the aforementioned chained reading desks, a type of library furniture that also survived well into the early modern period. In order to imagine our book in its earliest context, I would suggest to ‘visit’ the library at Walpurga’s Church in Zutphen, Netherlands, one of the five intact chained libraries featuring prominently an arrangement of said reading desks. An easy but informative read on chained libraries interspersed with pop culture references can be found on Ricke Elaine Ballard Gritten’s blog called Ricketiki.

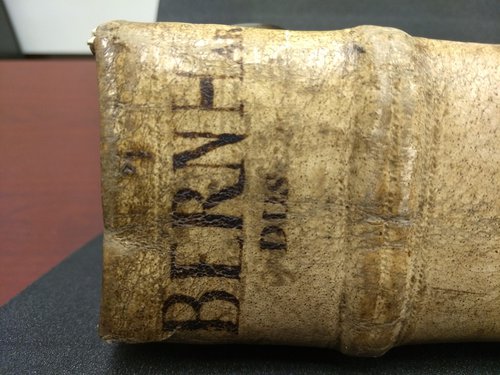

Detail showing the author name inscribed onto the books head compartment as well as one of the raised bands of the book’s bindings.

But, since the book’s spine shows lettering in its head compartment, it can be assumed that this book was at least at some point stored on a bookshelf with its spine sticking out.

The creation of every text has its context and so does every printed edition. By examining an individual copy, we can learn about a reader’s engagement with a certain text. The History of the Book is about the physicality of this engagement. It is my hope, however, that this glance at an over 500-year-old edition of an almost 900-year-old text corpus was able to demonstrate how every copy is not only a part of the History of the Book but how every copy has its own ‘life,’ its own history, which it will tell us if we are willing to listen.

The 1508 Renaissance edition of the works of Bernard of Clairvaux is part of SCRC’s rare books collection (Rare books, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University

References

Adams, Herbert Mayow, 1893. Catalogue of Books Printed on the Continent of Europe, 1501-1600, in Cambridge Libraries. London: Cambridge U.P, 1967, s.v. “B-704 Bernard.”

Auty, Robert. Lexikon des Mittelalters. München-Zürich: Artemis-Verlag, 1977, s.v. „B. v. Clairvaux“ by G. Binding.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “St. Bernard of Clairvaux” by J. R. Meyer, Accessed October 2, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Bernard-of-Clairvaux.

Suarez, S.J., Michael F. and H. R. Woudhuysen, eds. The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, s.v. “Petit, Jean” by D. J. Shaw.