The Digital Underground: Jim Meade

by Brittany Bertazon, Graduate Assistant for Digital Library Program

The Perils and Legacy of Audio Preservation at The Belfer Audio Archive, A Conversation with Jim Meade

This post pertains to the preservation of audio recordings currently underway at the Diane and Arthur Belfer Audio Laboratory and Archive (Belfer). Belfer is part of Syracuse University Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center. It is one of most inconspicuous buildings on campus; it is constructed partially underneath the hill adjacent to the Goldstein Alumni building and connects to Bird Library via an underground tunnel. Constructed in 1981, the building was the first structure anywhere in the world specifically dedicated to the restoration and preservation of audio recordings. Although the building was not constructed until 1982, the original archive collection was founded in 1963, with the acquisition of the Joseph and Max Bell Collection. In this August 2020 interview with Belfer’s audio engineer, Jim Meade, we explore topics such as risks involved in preserving different audio formats, passing on vestiges of audio preservation knowledge to the rising generations, and quarantine Work-From-Home (WFH) projects.

Brittany: Can you encapsulate what you do at Belfer?

Jim: I am an Audio Preservation Engineer at the Belfer Audio Archive, which is part of the Special Collections Research Center. My primary function is to digitize the Libraries’ audio collections, which cover everything from the earliest wax cylinders up through Shellac 78 records, including various formats such as analog tape, cassettes, wire recordings, and transcription disks. We have about 500,000 audio items in the collections.

Brittany: Is audio digitization how your position contributes to the Digital Library Program (DLP)?

Jim: Yes, digitization work is a primary contributor to the DLP. But we also contribute to digital stewardship of audio materials by helping the DLP folks to decide on the metadata standards that we use to describe digital audio objects. I spent a lot of time working on that with Mike Dermody (Digital Preservation and Projects Coordinator) and Déirdre Joyce (Head of Digital Library Program).

Brittany: What is the organizational structure of Belfer and how does that relate to your contribution to the DLP workflow?

Jim: Mike Dermody, [SCRC’s] Digital Preservation and Projects Coordinator, is our direct supervisor here at Belfer, so all of our workflows come through Mike. The engineers typically have a lot of involvement in that process as we will look at the collections and assess our input concerning what the most at-risk formats are.

Some formats are deteriorating more quickly than others. For example, analog tape is an at-risk format whereas our vinyl records will last quite a long time. Things of that nature guide our decision-making and will impact decisions as to what we digitize and when. We also consider the potential research value of the collection items.

Brittany: What are some of the projects that you have worked on with the DLP?

Jim: I worked with the metadata advisory group when it was still active, mostly in my capacity as an Audio Engineer. I was also involved in specifying some aspects of our back-end preservation system, which is Preservica. We looked into a lot of vendors’ systems for that, and my involvement was peripheral just for audio preservation input.

Brittany: Which digitization project are you currently working on?

Jim: I am currently working on the digitization of the Bell Brothers’ Latin American and Caribbean 45 rpm record collection, which are old single 45 rpm discs from the 1950s and 60s from all over the Caribbean, Latin America, Central America, South America, as well as a lot of imports from Spain and Portugal. I have been working on this collection for four years; it is a four-year project, and there are about 12,000 discs to be digitized, so that’s a lot of hands-on with discs and cleaning. I have worked on other things in the past, but that is the mainstay of what I’ve been doing for the past couple of years, and we’re hopeful (fingers crossed) that we’ll finish it early next year, in the first quarter. We will crack open the champagne when that happens.

Brittany: What equipment or technology do you use most often for this work?

Jim: We use a lot of analog equipment like professional record turntables and tape machines. We have specialized cylinder playback equipment, namely two Archeophone machines, manufactured to order and quite costly.

We then use very high-end analog to digital converters, like benchmark ADC16 converters, which we use consistently. We also use Steinberg WaveLab software (digital audio editor and recording computer software application) as our ingest front-end platform. Also, we have very high-quality audio cards for our specially designed computer workstations.

Machine used for cylinder audio playback.

Three images were captured by David Hoehl for a featured article “On an Overgrown Pathé,” which documented his visit to the Belfer Audio Laboratory at Syracuse University for TNT-Audio – online HiFi review viewable at https://www.tnt-audio.com/vintage/syracuse_e.html.

Brittany: What is one thing no one ever knows about what you do?

Jim: People generally do not understand the complexity of playing back old materials. There are two things specifically people do not understand:

- Every single format requires a specific type of machine to play it back on.

- There is no formal training or degree program dedicated to audio preservation in libraries or archives.

Firstly, keeping the machines in working order to play back things that are 100 years old, is a challenging thing to do. Our tape machines are nearly 40 years old, and parts are difficult to find, so people don’t understand the impact of equipment obsolescence. Many think you just get a record, put it on a record player, and put a needle on it. But we have a stylus kit at Belfer with 40 different styluses in it for all the different groove sizes. These cover a wide range of materials from the earliest manufactured records in the late 1800s to contemporary vinyl’s used today.

The complexity of the under the hood elements of preservation is not well understood. You have to understand the physics of sound, how the material was manufactured, and its limitations, what frequency responses one can get from it, etc. in order to line up those machines to give you the best possible playback. Digitization is complex and very expensive, so it is crucial to get it right the first time and get the very best transfers possible.

People also don’t understand that there is no formal degree program akin to the library science programs for the preservation of sound recordings. LIS programs barely touch on what we do. As a result, people in similar positions to mine come into preservation from other fields. My background is in broadcast, film production, video production, and network news. Audio preservation workers always enter the field sideways.

Brittany: How does an emerging professional learn to handle the delicate equipment without that kind of base knowledge and experience to be working with it?

Jim: The equipment is not too complex. You can read the manual and learn how to work the equipment if you have an audio engineering background or recently completed coursework that touches on audio engineering or studio recording technology. This is how we get our student workers who come in with some knowledge about audio and how it generally works.

Learning the intricacies of the materials is the most crucial thing to comprehend. Once you start handling old records, cylinders, and the like, there are specific techniques for each and specific techniques for cleaning them. You also have to know how to line up the equipment to playback legacy sound materials. With 78 rpm [revolutions per minute] records, there are scores of different manufacturer’s tone settings and varying stylus or needle sizes we use. You have to develop an ear for listening to it, especially younger people who are born-digital and used to listening to ultra-low noise digital stuff.

When they start listening to analog recordings, it is noisy, crackly, and hissy, and the inclination can be to get into the software and take all that noise out. But you can’t do that because then you’re taking away half the signal as well, so you have to educate the younger engineers into understanding what analog sound is and what we’re trying to preserve.

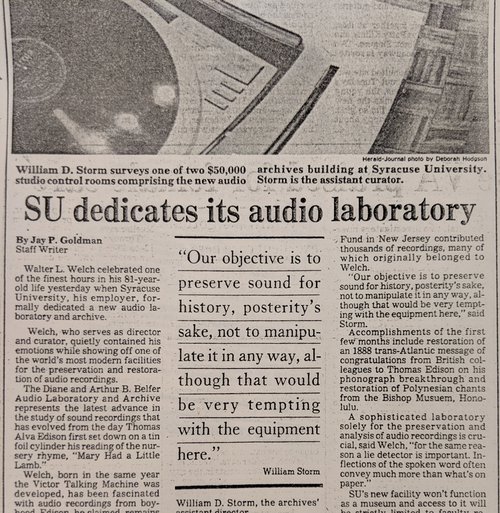

Herald-Journal Newspaper article “SU Dedicates its Audio Laboratory” written by Jay P. Goldman in 1982. This press clipping includes a relevant block quote by William D. Storm, previous Director of Belfer Audio Laboratory and Archive at Syracuse University, which reads “our objective is to preserve sound for history, posterity’s sake, not to manipulate in any way, although that would be very tempting with the equipment here.”

Brittany: Do you have a group of younger people working with you regularly and what kind of work do they do?

Jim: Currently, we have one student preservation assistant, Jenny Jian, who’s working with us at the moment, helping us do transfers. She directly assists me, which entails dropping the needle in the groove, monitoring, and digitizing those discs. I hand off work to Jenny comprising discs that are in pretty good condition. If she comes across serious condition issues, those discs are passed on to me because there are manual techniques that you can use that can be dangerous if you don’t have that skill base.

All materials for digitization are analog, which is why engineers like me are often of a certain age, born in the analog era and maturing into the digital world, understanding the analog side of things, and trying to pass that on to a younger generation of rising professionals. This work is a niche, but I think there are many people interested in it, and a lot of younger engineers are getting involved in it as well, which is a good thing. I am hoping that those skills will transfer across.

NOTE: The Belfer Audio Archive hosts preservation assistant positions and internships for any students interested in developing skills in audio preservation. The assistant mentioned in this interview has since graduated and Belfer will be looking to potentially hire for the summer 2021 session. Interested parties should also consult the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) resources website which provides contacts for related professional organizations, discussion listservs, training opportunities, and other sites of interest.

Brittany: Speaking to both the technicality and physicality of this work, how did quarantine fair for you?

Jim: Quarantine was a nightmare for me because of the amount of hands-on work I do in the studio. I have to be in this studio to access all this equipment. Fortunately, I had a couple of weeks of work lined up that I could do from home remotely, like editing files already digitized. It was a bit glitchy over the web, but I learned to tell the difference between clicks coming from the network lag and genuine audio clicks, which takes a bit of experience. That took up about two or three weeks of work, and then I assisted with other projects.

Working from home was very strange for me. It took some getting used to; I missed working on the projects. As the months dragged on, I realized how behind we were getting on audio projects where a digitization aspect was present, which was a big concern. I was constantly thinking: “my God…when are we going to get back to doing this?”

NOTE: At Syracuse University, all students and staff were given a quarantine order to not enter the premises as a result of the initial onset of the pandemic in March 2020. Only essential staff members were granted access to buildings after roughly three months of quarantine. During this transitory period, SU Libraries shared digital projects, colloquially referred to as the Work-From-Home (WFH) projects, to give both student workers and staff from across the library opportunities to enhance object records. This was in part created for those whose normal tasks were hindered by the current circumstances, so that they could continue working from home. Using documents and correspondence from the Marcel Breuer Digital Archive, the first project involved transcription of 1,986 handwritten pages to create machine readable transcriptions for later enhancement of digital objects. Another project similarly used scanned images from the Street & Smith Dime Novel collection to create rich, accessible descriptions of Dime Novel cover art for low/no-vision users with techniques borrowed from art history. These projects were conceived by Michele Combs, Lead Archivist at Syracuse University Archives, and initiated with the help of Déirdre Joyce, Head of the Digital Library Program.

Brittany: Were the other projects you mentioned any of the Work-From-Home (WFH) projects created by Special Collections and the DLP?

Jim: Yeah! I worked on both of those, especially the descriptions of the Street & Smith Dime Novel Covers. I did quite a bit on that, and I thought it was fun. It was way more difficult than I thought it was going to be. Trying to describe the still cover picture was quite tricky, but I think I got it down in the end (at least I think I did). During the early phases, Michele Combs, WFH project lead and content specialist, gave us great pointers on what to do, what not to do, what level of detail, and what was not necessary to include in the description. Once we got all of that out of the way, I started to really understand it.

It was not unlike what I do in audio preservation! In the Marcel Breuer Archive Transcription project, I looked at documents and visually scanned the handwritten portions. It was hard for me because I was mistakenly engaged with the meaning of the text, whereas that was not the main focus. I had to get past that and analyze the document objectively, which I realized is the same thing I do with audio. In sound recordings, I am listening for the noise and the anomalies (the messy bits) just like I am searching for the anomalies in handwritten notes in the Breuer Archival documents.

Brittany: When do you feel most fulfilled in your role?

Jim: When I get feedback from people who use the sound materials, it is at that moment that you realize how important it is.

The other thing that excites me is when people come in for studio tours and instructional sessions. I enjoy instances where we get to show off what we do because people have no idea. I also like to talk about the old analog stuff to people who are studying audio engineering. Once they understand the nature of early acoustic recording, you can see the moment they realize how fantastic it was that people were able to record audio with no electronics and nothing that plugged in—no microphones, no nothing. Yet, they were still able to make these relatively fantastic recordings. Sharing that knowledge with people excites me. We get many research inquiries through Special Collections, and that’s another vector by which we share our knowledge.

Brittany: Are you still going to be hosting students for tours and the like with the pandemic still in play?

Jim: I do not think so. Our plan is to produce a video tour of Belfer for virtual learning. I usually do about 20 tours and presentations a year. Our class presentations are all tailored for the particular group. Unfortunately, I do not think we’ll be doing a lot of that this year—at least that is not the current plan.

Brittany: Is the Belfer Laboratory and Archive usually accessible to the public?

Jim: The door to the premises on the outside is always locked. There is no public access without an appointment.

NOTE: At this time, in-person tours remain suspended due to COVID protocols. The landscape on this is constantly shifting. In the interim, Belfer continues to participate in live online SCRC instruction sessions and has produced recorded materials for several classes. Several instructional recordings also exist on Syracuse University Libraries’ social media sites.