The “Straight-Backed, High-Nosed, Stiff-Necked, Great British Young Lady”: Music and Art of Liza Lehmann

Written by Amanda DuBose, Music and Performing Arts Librarian; Danny Sarmiento, Curator, 20th Century to Present, the Special Collections Research Center; and Irina Savinetskaya, Curator, Early to Pre-20th Century Curator, the Special Collections Research Center

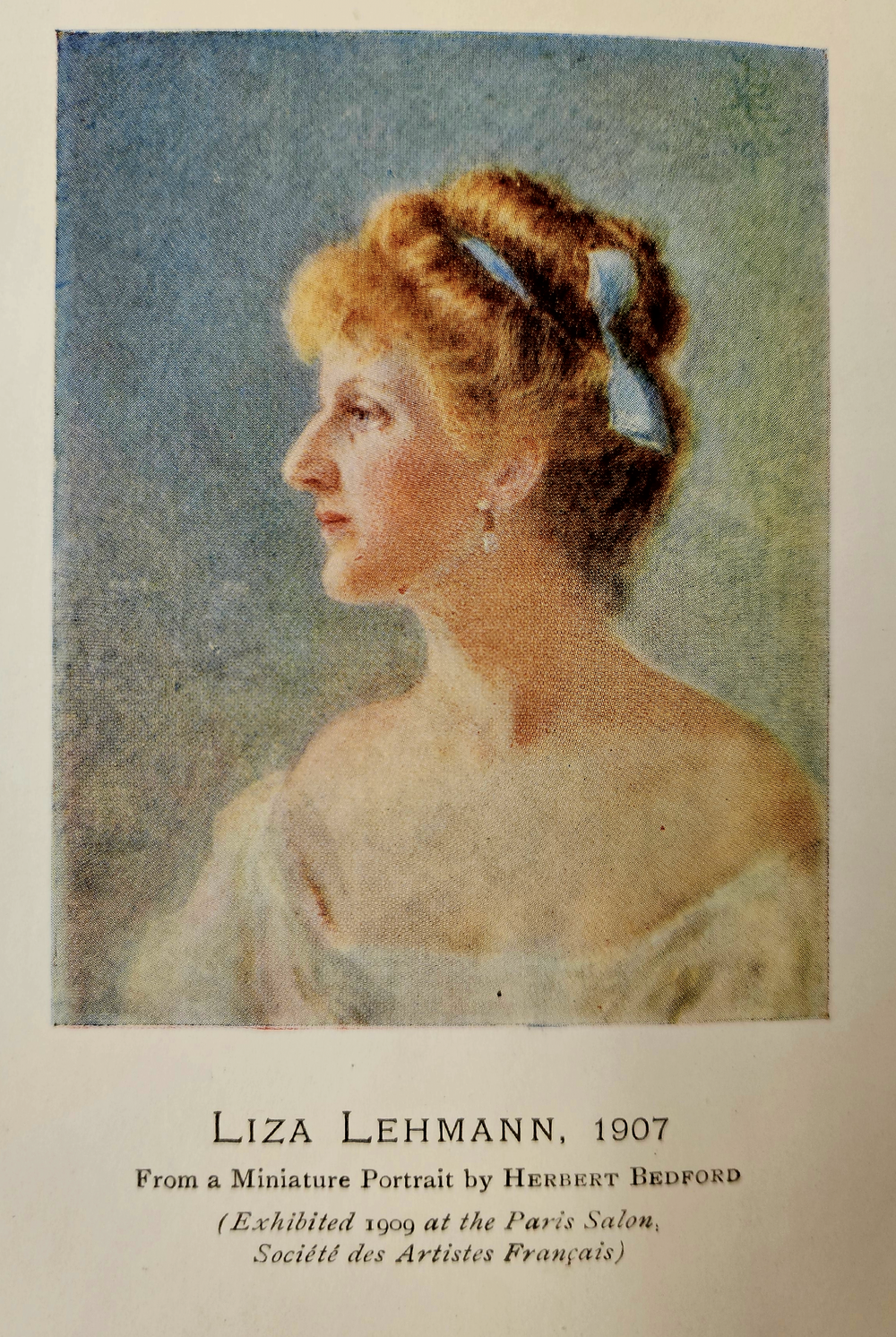

Liza Lehmann (1862–1918) was one of the most prolific song composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and an influential vocal pedagogue (Fig. 1). Between 1890 and her death in 1918, Lehmann published some 334 songs and cycles – the most by any female composer in Great Britain and the United States during that period.[1] Lehmann was elected the first president of the Society of Women Musicians and published several volumes on song and recitative practice and pedagogy. The success of her writings was supported in part by her already established reputation as a singer, with early encounters with Verdi, Liszt and Clara Schumann proving to be influential in both respects.

Liza Lehmann’s professional musical career began at the age of 23 at a Monday Popular Concert,[2] a well-attended concert series in London. Her mother was a music teacher, composer, and arranger in her own right who oversaw her early training. Liza went on to study with well-known musicians of the time such as Alberto Randegger, Jenny Lind and various composers across Europe from a young age. She was recognized for her pleasant soprano voice and interpretations of new works by Liszt and of 17th- and 18th-century English songs she discovered in the British Museum.[3] Her career was encouraged by no less than Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim. She gave a farewell concert at St. James’s Hall in 1894 and retired upon marrying Herbert Bedford, also a composer and painter.[4] From then forward she devoted her musical efforts to composition.

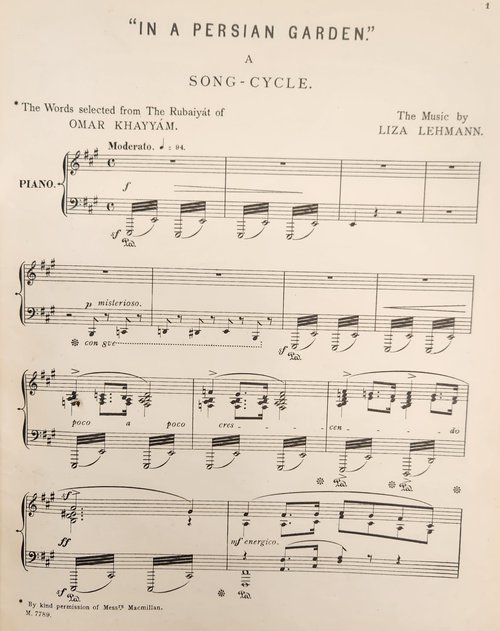

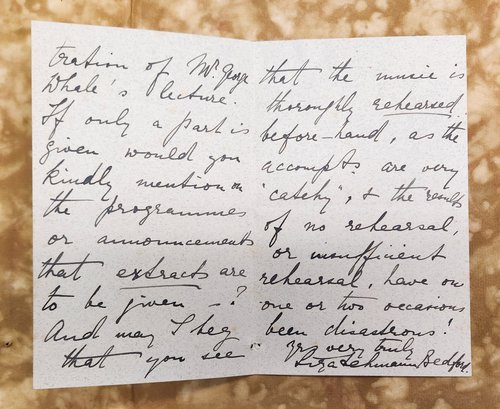

Included among SCRC’s holdings related to Lehmann is a first edition of In a Persian Garden (1896), a song cycle on translated texts of the Rubāiyāt of Omar Khayyām (M1558 .L523), her most ambitious and commercially successful work (Fig. 2). Though now regarded as one of the first important English song cycles, In a Persian Garden was initially rejected by many publishers due to its experimental structure. SCRC’s copy is especially interesting given the hand-written letter that accompanies it. Signed, “Liza Lehmann Bedford,” the letter implores the recipient, “I beg that the music is thoroughly rehearsed [sic] before-hand”. And while context suggests that the letter was indeed written to a composer charged with delivering a public performance, one easily imagines Lehmann’s appeal intended for all hands finding the book in their possession.

Fig. 2: “The Music by Liza Lehmann.” In a Persian garden, p. 1. Syracuse University Libraries.

Figs. 3 & 4: A letter signed by Liza Lehmann, found in the Libraries’ copy of In a Persian garden. Syracuse University Libraries.

Lehmann’s compositions encouraged the growth of the song cycle, which was not commonly used by British composers of the time, and the English morality genres. The births of her children in 1897 and 1900 inspired her to compose song cycles for children and those reflecting on childhood, such as The Daisy-Chain based on poems by Robert Louis Stevenson and other poets.[5] In 1904, she became the first woman to be commissioned to compose for a musical comedy and her Sergeant Brue was a stage success with 290 performances in two years. Late in life she took a position at the Guildhall School of Music in London but the death of her elder son, Rudolph, during military training exercises in the midst of World War I so devastated her that she was unable to continue these duties the remaining three years of her life. Overall, she left three extant stage works, five works for voice and orchestra, 28 song cycles and collections, and many other musical works, both big and small. She also wrote a pedagogical manuscript, Practical Hints for Students of Singing, and a memoir of her life and career, The Life of Liza Lehmann, which appeared posthumously in 1919.[6]

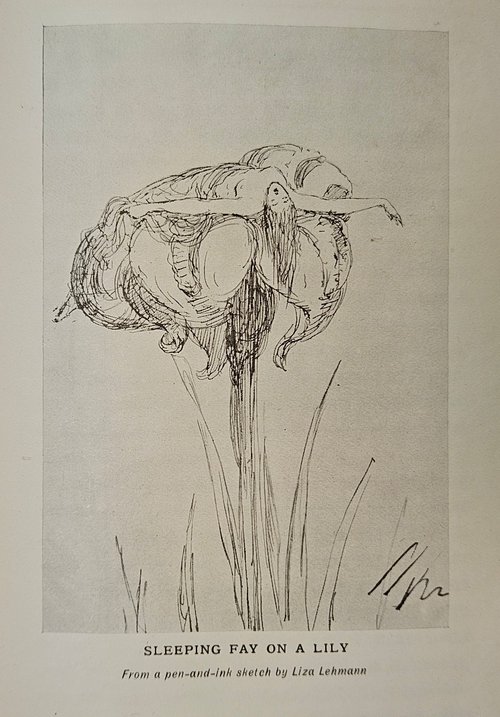

In that autobiography, which is also part of the Libraries’ collection, Liza describes her teenage artistic pursuits: “My father, who was anxious that I should become a painter, encouraged the sketch-book habit, and was very irate if I traveled with my eyes glued to a novel instead of jotting down effects of sunset or of Alpine scenery. For a short season I actually attended classes at South Kensington, drew from casts, and had private lessons in perspective… But, as with my mother, music lured me the more strongly.”[7] In the book, Liza included an example of her early drawings–“a sleeping fay on a lily’” (Fig. 5), which bears great resemblance to the artwork in her sketchbook, purchased several months ago by the Special Collections Research Center at Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 5: “A sleeping Fay on a Lily.” Drawing by Liza Lehmann. The Life of Liza Lehmann, plate opposite p. 30. Syracuse University Libraries.

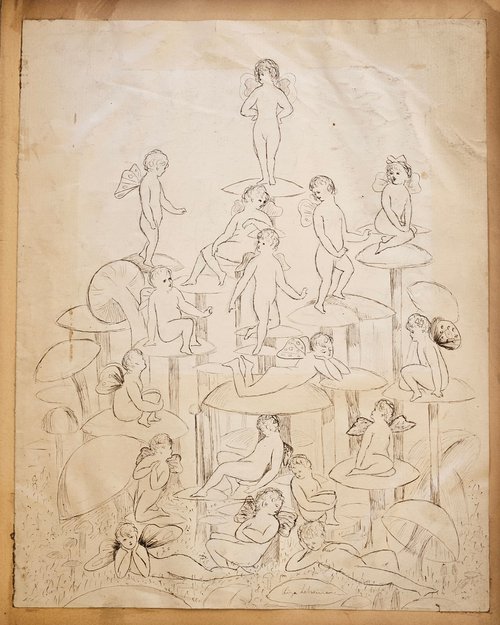

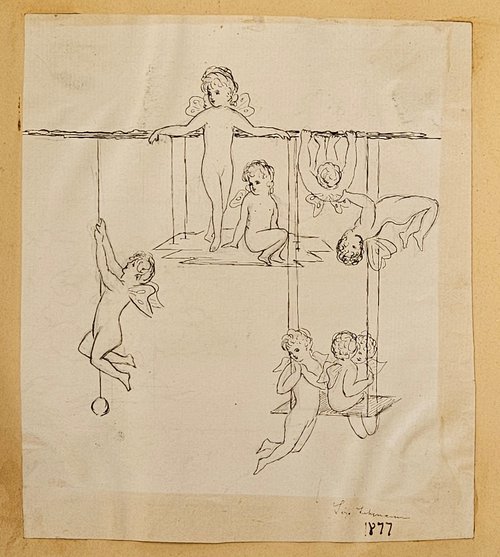

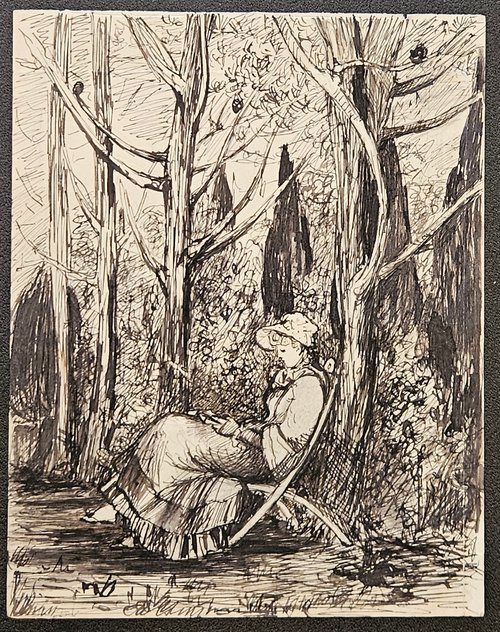

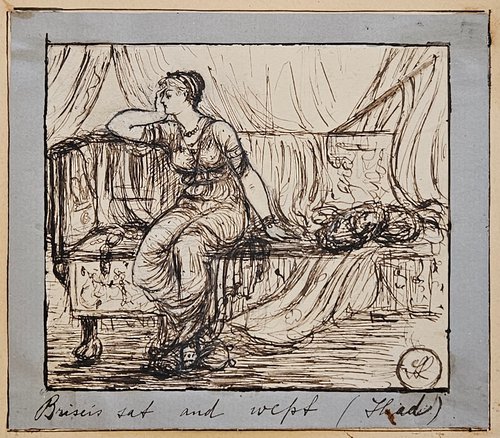

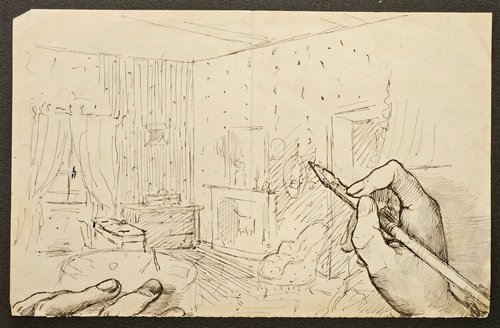

Mostly dating from the 1870s and 1880s, Liza Lehmann’s sketchbook is a curious window into the life of a teenage girl in the Victorian era. It is filled with fairies–a great preoccupation of Victorian artists: a fairy ensnared in a spider’s web (Fig. 6); a fairy “watching the sun sink on a mushroom”; “the winter fairy made a prisoner”. Cherubs also abound: a group of winged angelic-like babies perched on mushrooms (Fig. 7) and cherubs gleefully swinging on swings and ropes (Fig. 8). Most of the pages are brimming with images of women, portrayed in Victorian-era attire, and of fictional female characters. Among them are a drawing of Lehmann’s mother in Kensington gardens (Fig. 9); an intimate portrait of a woman holding a child (Fig. 10); Iliad’s Briseis (Fig. 11); a drawing of Bo Peep; and sketches of the singer Minnie Hank in Carmen. Several landscapes and domestic interiors (including a trompe-l’oeil of her own hand drawing her room are also present. Some of the sketches appear to be illustrated letters from Liza Lehmann to her father, which detail her daily life and are interspersed with amusing notes, including this one: “I remain the straightbacked, highnosed, stiffnecked, great british young lady.”

Fig. 6: A fairy ensnared in a spider’s web. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 7: Cherubs resting on mushrooms. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 8: Cherubs swinging on swings and ropes. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 9: Lehmann’s mother in Kensington gardens. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 10: A woman holding a child. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 11: “Briseis sat and wept (Iliad)”. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

Fig. 12: Trompe-l’oeil of Liza’s hand drawing her room. Liza Lehmann Sketches, the SCRC, Syracuse University Libraries.

In her address as the inaugural President of the Society of Women Musicians, Lehmann quoted the novelist Robert Hitchens, saying, “Art is a door through which we pass to our dreams,” and further added that she herself had “the habit of dreaming on both sides of the door.”[8] It is an apt self-portrait of Lehmann as artist-educator and – while she claimed that she was “scarcely fitted for such a position,” – her presidency with Society of Women Musicians also marked her as a trailblazer and advocate for women, both in the profession and society at large. The organization was intrinsically connected with the suffrage movement, championed womens’ independence and solidarity, and remained active in these regards some 60 years after Lehmann’s tenure – confirmation of Lehmann’s closing remarks that “the Society of Women Musicians has come to stay [...] to the beneficial influence of its sincere and noble aims on all who come into contact with it.”[9]

To discover her musical works for yourself, you can explore her scores available on the fourth floor of Bird Library on online from HathiTrust and IMSLP. This library has access to many modern recordings of her works through Naxos Music Library and Alexander Street Music. While the Belfer Sound Archive does hold a number of period recordings on both disc and cylinder, the cylinder digitization project has yet to make these particular recordings available; never fear, the Discography of American Historical Recordings has many of these early recordings available digitally.

[1] Reynolds, Christopher. "Documenting the Zenith of Women Song Composers: A Database of Songs Published in the United States and the British Commonwealth, ca. 1890–1930." Notes 69, no. 4 (2013): 671-687.

[2] “Advertisement,” The Musical World 63, no. 47 (November 21, 1885): 736–736.

[3] “Lehmann [Married Name Bedford], Elizabeth Nina Mary Frederica [Liza] (1862–1918), Composer and Singer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed April 10, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/40559.

[4] “London Concerts,” Musical News 7, no. 177 (July 21, 1894): 56–56.

[5] “Lehmann, Liza,” Grove Music Online, accessed April 10, 2023, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000016324.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Lehmann, Liza. The Life of Liza Lehmann. London: T. Fischer Unwin, 1919, p. 29.

[8] Ibid., p. 173.

[9] Ibid., p. 179.