The Digital Underground: Digital Competencies

by Brittany Bertazon, Graduate Assistant for Digital Library Program

Cultivating Digital Competencies during Grad School

Over the past two years, Syracuse University Libraries’ Digital Library Program (DLP) has employed three graduate students. This post features interviews with DLP Graduate Assistants Ambar Roy, graduate student in enterprise data systems and information security management, and Kiley Jolicoeur, library and information science graduate student. The Libraries have become progressively reliant on graduate student employees to help perform duties essential to everyday operations. Library graduate student employment provides reciprocal benefits; it allows students to apply theoretical concepts and foundations from their studies in the School of Information Studies (iSchool) to a real-life work setting, while the students offer instrumental services to various components of the DLP. Graduate Assistants contribute work in areas such as metadata production, digital imaging, institutional repository management, data migrations, clerical research, digital rights management, and assisting on numerous digital projects and initiatives. Integrating student assistants in digital repository workflows and collections management affords graduate students empirical experience. “Learning by doing” equips students with more holistic, immersive practice engaging in professional decision making, formulating innovative solutions to problems, and developing confidence for future work.

Brittany: Tell me about your role?

Ambar: My main job as a Graduate Assistant in the DLP is to support the institutional repository’s ingest process of digital manuscripts. Digital manuscripts might consist of dissertations, research papers, presentations, events, anything of the like.

Kiley: I usually work on metadata projects, but I’m always happy to work on anything that comes up, so there’s a lot of flexibility with what projects I work on.

Brittany: How does your position most contribute to the DLP and how long have you been involved?

Ambar: The main component of my job is adding approved digital manuscripts to the repository when everything gets authorized. I have been performing digital collection management for the institutional repository since I started in January of 2020. I also conduct open access policy checks of digital manuscripts and recommend procedures to the creators of the documents for ingest.

Kiley: I started in February of 2020 and most of the work that I contribute is in regard to metadata.

So that’s working on the new system, Quartex, getting our metadata application profile up and running, and cleaning metadata that already exists on collections or creating new metadata for collections that already exist.

Brittany: What areas do you primarily work with, and do you participate in other areas as well?

Ambar: Supporting the institutional repository is my main duty, which is backend administration of SU’s Open Access Institutional Repository called “SURFACE”. The Libraries use a platform called Digital Commons which is hosted by Bepress. Before posting anything on SURFACE, I research open access policies and make recommendations on how best to comply with the publisher’s publication policies. I was trained and supervised by Patrick Williams, Lead Librarian for Digital and Open Scholarship, who manages communication between different departments within SU and the Libraries. Posting any manuscript on SURFACE involves an ingest process of adding metadata such as DOI, ORCIDs, embargos, etc., updating each series of digital collections, and finally updating the front-end website. We discuss updates to the SURFACE website during our weekly meetings with the SURFACE team: Déirdre [Joyce, Head of the Digital Library Program], Patrick, Suzanne [Preate, Digital Initiatives Librarian], and me. Other administrative activities involve granting and removing access to collections and updating the privileges of back-end users based on policies set by DLP leadership. I also help manage the SURFACE email and the influx of email requests.

I have been working on many other projects in conjunction with this work. One in particular is the data extraction from the SURFACE repository, which has been a challenge for the librarians. I worked on automating data extraction of metadata fields.

Kiley: Mostly metadata. I’ve worked on a couple different projects that were not metadata related. I did a benchmarking study to examine our program in relation to other programs at comparable universities. I’ve worked on some administrative things, clerical work, organization, etc. But the bulk of the work is definitely in metadata, which is good because that’s also what I’m interested in.

Brittany: What equipment or technology software do you use most frequently? What’s most necessary for your role?

Ambar: Microsoft Excel is my bread and butter. When working with large data sets, I often use Excel or OpenRefine, an open-source desktop application for data cleanup and transformation. I use Zoom for video creation, especially for creating tutorials to be made available on video.syr.edu. For checking open access status for digital manuscripts, I use Sherpa Romeo, an online resource that aggregates and analyses publisher open access policies from around the world and provides summaries of publisher copyright and open access archiving policies on a journal-by-journal basis. For API (Application Programming Interface) usage, I have used Postman, which is an application that developers use to create, share, test, and document APIs.

Kiley: Microsoft Word and Excel are my contentious best friends, but mostly I use OpenRefine for any kind of data cleaning and manipulation.

See Open Refine video tutorial

Brittany: What is one thing that no one ever knows about what you do in your current role?

Ambar: For the institutional repository ingest processes, there are professors or researchers who reach out to us with their documents, and we recommend what process they need to follow in order to make their work open access. The amount of communication is extensive. Once everything is approved and finalized, we post the documents and then we inform them that it is now live in the system with a link. A lot of people within the University and other institutions make requests and want to adopt open access.

Another thing that the repository requires is training on how to use, specifically how to pre-upload submissions on SURFACE. So, our team must offer training sessions to people on how to manage the repository and execute the procedures most effectively for uploading content. Usually, Patrick does that for everyone as a routine part of his job. However, I’ll be joining him in the next training session as well, which is something I am eager to add to my work.

Kiley: I think what people usually don’t know, especially people who aren’t familiar with how broad librarianship is as a field, is that the information that we have that describes our digital objects has to first be created. It doesn’t come out of vacuum; we have to create that information. Then it also needs to be maintained and changed as we migrate it from system to system or as we decide to change our standards. It always requires care. I had a conversation recently with someone who asked what I did, and I described it as being a zookeeper. The metadata are our zoo animals that we have to feed and clean. It always requires attention, and you can’t just leave it in its pen; you always have to make sure that it’s healthy.

Brittany: What’s your favorite undertaking that you have worked on so far?

Ambar: Earlier this year, the DLP team successfully transitioned to Orange Tracker, a Jira tool, to track different issues and sub tasks. While LITS was setting it up for DLP, I used my prior experience with using Jira and introduced an interim step to track issues, especially SURFACE email ad-hoc requests. It involved maintaining a simple dynamic excel spreadsheet on Microsoft Teams with column names the same as a Jira service request/ ticket, such as Issue title, Assigned To, Date Raised, Resolution Date, etc. This made sure that none of the ad-hoc requests were missed by the team. It also allowed me to drive SURFACE meetings for a few months until we completely transitioned to Orange Tracker. Orange Tracker has helped improve the team’s efficiency greatly.

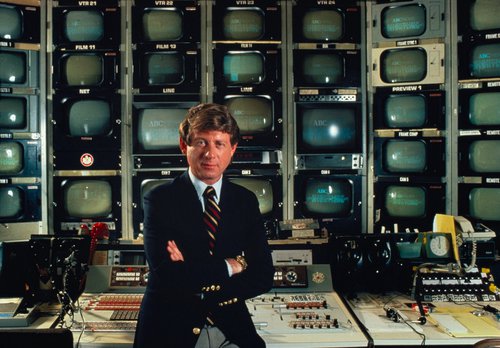

Kiley: I did really enjoy working on the Koppel Collection. The Koppel Collection consists of episodes from the late-night news television program called “Nightline” that Ted Koppel, host of the show and Syracuse University alumnus, donated to the University. Nightline officially started in 1980 as a byproduct of a series of special reports about the 445-day-long Iran hostage crisis in 1979. While it still remains on the air today, Ted Koppel stepped down from Nightline after 25 years as anchor of the program in November of 2005. There’s a vast number of digital objects in that collection, largely video content of ABC News productions with Ted Koppel. There are approximately 6,600 episodes of Nightline, and each one of them is a video that was digitized with an accompanying audio transcript. Most of them came from ABC, but some of them came from a vendor. I was granted the opportunity to create new descriptions and clean up or add to the existing descriptions, ensuring that the names of people appearing in the episodes matched their authoritative forms, and that their contributor roles were appropriately assigned. I had to use both the actual video itself and the transcript that was attached to it. For example, if Betsy Aaron was in the episode, what role was she playing? She is a news reporter, so I associated her name with that role to add context and help further describe that collection.

Part of what I did was assigning Wikidata and Library of Congress Authority numbers to everything, so some investigative research was required for verification purposes. That was the bulk of the work that I did. It sounds very straightforward, but it was surprisingly not. I made I think over 2,000 corrections and additions combined to the collection over the course of a couple months using OpenRefine. I cleaned the data content in OpenRefine and in our back-end software. It was very interesting to work on considering it is a collection of primary broadcast sources. I never would have been exposed to some of the things that I learned through working with that collection.

Photo by Joe McNally. In front of a wall of retro televisions, Ted Koppel poses in the control room for the program Nightline located at the ABC News Washington Bureau, Washington, D.C. This is one the first promotional images of Ted Koppel as they launched Nightline in response to the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979. Approximately 6,600 episodes of Nightline were donated by Koppel, an alumnus of Syracuse University, in addition to correspondence, photographs, cartoons, awards and notebooks.

Brittany: Do you have any projects or items that you’re working on right now or in the near future significant to the DLP?

Ambar: Right now, I am working on improving our repository email request process. The problem with the SURFACE email is that we get an enormous influx of email requests, which are often from outside the University and not always necessary for a response. In order to avoid missing emails or disregarding insignificant emails, we are planning on migrating to a ticketing tool called OrangeTracker. It will give us better understanding of the tracking history of all issues and generate more accurate reports, improving on the current spreadsheet we use. We are still in the process of implementing the steps, but we have created the workflows to be put in place. So, when an email comes in, we can actually click on it and immediately generate a ticket for it if it is required. This will improve our performance, allowing us to reply to the right people at the right time.

Kiley: I’m working on the Gerrit Smith collection right now. Gerrit Smith (1797-1874) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, politician, and philanthropist. I am specifically working on the Gerrit Smith Pamphlets and Broadsides Collection and a few other items from the overarching Gerrit Smith Collection. I am using all of the metadata that was in our METS Manager [a locally developed database that manages the METS (metadata encoding transmission standard) records which provide structure to our current digital repository] and putting that together with all of our catalog records. So, I stripped all of our cataloging data into manageable records and then imported some of the data from the METS Manager to combine them because there’s some information that isn’t in the cataloging data. Now I’m pulling everything apart and getting rid of the extraneous information, the data fields that are only applicable to the catalog record. I am taking that combined catalog data and METS information, pulling it apart and combining it in different ways to turn it into something that matches our metadata application profile. Eventually it will go into Quartex. Then, I will describe these objects so we can make them available to users with descriptive metadata. I’m doing a lot of data manipulation. I’m learning tricks on how to do things with OpenRefine to merge the data. It’s definitely an iterative process that isn’t going to be finished for a while. We have to interrogate how are we going to do different collections and whether we need to readdress certain aspects when creating the metadata application profile.

Brittany: How did quarantine impact your work?

Ambar: Because we were given our laptops, there wasn’t any challenge with respect to completing work or academic studies. Working from home certainly changed the way the way I was living. Everything became remote and I started feeling isolated. Halfway through one week, I realized that I hadn’t left my floor in the house. After that, I bought a bike to be able to get outside a bit.

Kiley: I was able to do everything that I would have done in the office because we have access to everything remotely. Sometimes it took some figuring out for how I might need to approach projects differently. I was able to use the University’s remote desktop for certain scenarios and to share files. We have the infrastructure that we need to be able to collaborate efficiently, so it wasn’t difficult. The only problem that I experienced was internet quality at home. But I was usually able to find ways around that; I don’t think we really faced much difficulty as a team.

Brittany: Has working with the DLP filled any curricular gaps in your graduate program?

Ambar: Working with the DLP gave me the chance to see information policies being made and justified in action. Information Policy (course IST 618) was an important and required course in my master’s curriculum. I learned the vision of DLP from Déirdre, and how the DLP team worked closely in making information policies that empower SU students, alumni, and faculty in the field of research and scholarship.

I’ve also taken an iSchool selected topics course (IST 718) not covered by the standard curriculum called Big Data Analytics which is a tough but useful course for my professional aspirations. Working at the Digital Library Program has given me real-life practice to implement the concepts and theories I’m concurrently learning in that course.

Kiley: Yes, it has definitely filled curricular gaps. I came into this program very interested in academic librarianship, and I didn’t really know that much about archives. I read the job description for what is now my DLP role and thought that it sounded a bit different than what I had imagined doing, but it sounded fascinating. It’s definitely changed my understanding of what librarianship is in the sense of digital work. What we do at the DLP is not as “public facing” as a lot of traditional librarianship roles. Being able to learn the actual practice of handling digital collections and management systems, especially from the aspect of apprentice metadata librarian, was a very valuable experience to combine with basic theoretical introduction to library and information science through the curriculum. It helped me when I took IST 616 (Information Resources: Organization and Access), because I already had exposure to some of the concepts and felt more comfortable and confident during group projects and presentations, since I could explain concepts in terms of something that I had worked on.

There isn’t really an opportunity to learn about digital librarianship or digital archiving and theory, despite some classes in the curriculum. There usually isn’t enough interest to be able to support the class, so they aren’t routinely offered. Through working at the DLP, I was able to understand what digital and metadata librarians do in real life. I was able to understand this is what I want to do, and this is where my interest truly lies, though I’m still interested in academic librarianship in its broader scope as well.

Brittany: What changes to the DLP do you foresee in the future or recommend the DLP work toward?

Ambar: We are already working towards most of them, like the SURFACE email improvements implemented in Orange Tracker. Only having worked with the DLP since January of 2020 in the midst of a pandemic, I wish I could have dived into more things that the DLP does such as Preservation, Quartex, Digital Stewardship and Preservica.

Kiley: I’m looking forward to what this team will look like in two years when the empty positions are filled. By that point, I think this team will become a tour de force in digital collections. Just the future state of what we’ll be capable of, what new projects we can take on, what is that going to look like, and what kind of exposure is that going to get once our digital collections are fully migrated. But I think something that we need to do better is the public facing side—this is what we do, this is what we’re working on, and this is what’s happening. I think that’s why this blog is super important too; people can understand what we’re doing and why we’re important. You’re seeing our digital work and we need to be clearer about what our digital labor entails. Being able to communicate our value in what we do is crucial (which is also important across all areas of librarianship, archival, and information fields). That kind of exposure of the labor and the collections is something that we can and will do better as we grow. Especially doing digital work—you don’t work directly with the community. Invisible digital labor is an issue that needs to be constantly addressed.

Brittany: What is the future trajectory of your career pathway, and do you think the DLP has influenced or shaped that?

Ambar: My aspiration in the future is to be a Cloud Architect, an IT specialist who develops a company’s computing strategy. I do a lot of research on cloud management and cloud computing. The University already has a lot of its content on cloud, which I have worked with a bit. Although I would like to transfer my skills and expertise gained from the Syracuse University iSchool and SUL Digital Library Program to work in a technology product company one day.

I feel grateful to have been a part of DLP as very few people get this opportunity. This experience improved my skills in Data Analysis, Project Management, Information Policy Analysis, and Communication, which will be extremely valuable in shaping my career trajectory.

Kiley: I have transitioned to working full-time this summer and will be starting my internship with the DLP at the beginning of July into September. My internship is going to be examining and proposing an implementation for linked data for our digital collections and how we can build off our existing infrastructure to develop that further. In addition, to identify what possible platforms to use for the process of creating that linked data and exposing it into our workflows. I graduate in December of 2021.

Beyond that, my ideal job would be to end up as a metadata librarian at a university or liberal arts college. It is quite an exciting prospect to me since the role of a metadata librarian looks a little bit different at different places. I would love to work at a university working with the university’s unique archival collections. I look forward to working with unique materials, as well as other librarians and archivists who possess such different skill sets and expertise in a team environment, because it doesn’t happen with just one person.

NOTE: Ambar Roy has recently graduated from Syracuse University and will be joining Securonix, a next generation cybersecurity big data company as an Associate Cloud Security Engineer in July of 2021. His parting remark is: “Thanks to the knowledge and experience I gained from Syracuse University and SU Libraries’ Digital Library Program, my dream of working in a technology product company has come true!”