Pieces of Puerto Rico: Plastics and Protest

by Jana Rosinski, Curatorial Assistant of the Plastics Collection

I know when I’m looking through collection materials that what I sit with are only pieces. There’s no such thing as a complete story, especially one that can (re)tell itself; the pieces make the act of storytelling possible. When looking at objects from the plastics collection, an established narrative exists between the impact of polymers and American industry and ingenuity. From this narrative I can pull lines and follow traces to company histories that have given rise to the corporate giants behind so many items, to the genius of persons on the edge of discovering the next new material, or the chemical processes that have created this ubiquitous material and its ubiquitous legacy.

In researching the Branchell Company within the Edward Hellmich Papers, I found myself looking at small brightly colored catalogs for the homemaker to order fashionable dish sets, pages and pages of tissue thin documents of legalese of Hellmich Manufacturing Co.’s growth with the establishment of Branchell, and plastic sleeves of black and white snapshots of smartly dressed women inside of a factory making dishware. The story of the labor/ers that made plastics is a much less told narrative, but one that I think should be as prevalent as the story of the science they helped transform into the products of our material culture. These hands operating industrial presses and adding finishing touches to designer dishes, captured forever working in photographs: What connected these women to plastics? Here were dishes designed by an American, with Chinese character adornment, being manufactured by the hand labor of Puerto Rican women during a politically fraught period of socioeconomic shift—how did these pieces connect?

Workers operate a semi-automatic finishing machine inside the Branchell factory, Bayámon, Puerto Rico. Edward Hellmich Papers.

A worker operates a 200-pound press to create vegetable dishes. Edward Hellmich Papers.

A worker uses a press to make dinner plates. Edward Hellmich Papers.

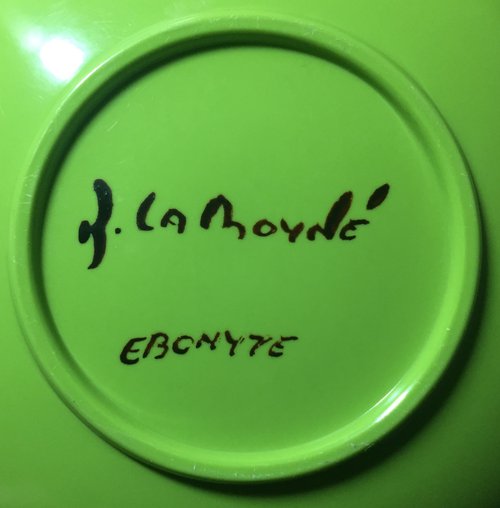

Lime colored bowl and lid with bamboo handles and hand painted characters from the Ebonyte line; designed by industrial designer Kaye La Moyne, a frequent collaborator of Hellmich/Branchell. Edward Hellmich Papers.

Kaye La Moyne’s signature on the bottom of bowl in the Ebonyte line. Edward Hellmich Papers.

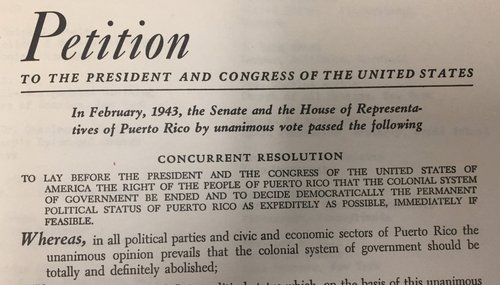

Petition to abolish the United States’ colonial governance of Puerto Rico. Dated during the Second World War, a time when the island was occupied by a number of U.S. military bases, and its people were once again required to bear arms for the U.S. Socialist Labor Party Pamphlets.

Planting the Root for Plastics

The plastics collection area within the SCRC contains objects, material samples, rare books, and manuscripts from the mid-twentieth century, a time of rapid development post-World War II in the chemical industry and in manufacturing. A surplus of plastics engineered for military craft, weapons, and technology, along with the technology suited to their production, needed to transition from the military-industrial sphere to the realm of public domestic goods. Ranging from integration into the bodies of automobiles, to the bristles of toothbrushes, plastic became just about anything one could imagine. Dishes became plastic out of practicality.

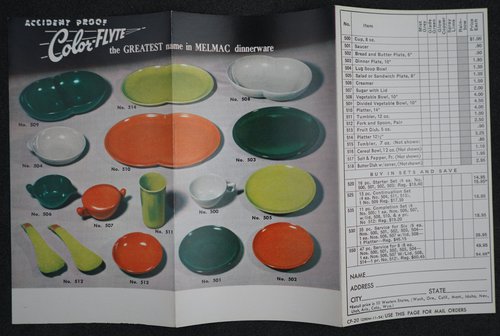

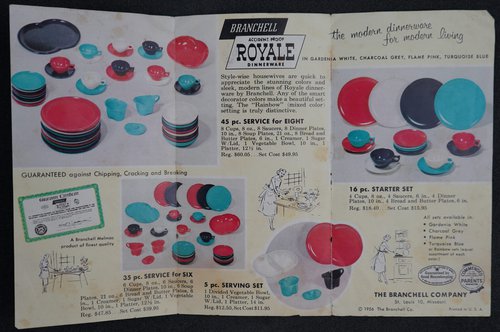

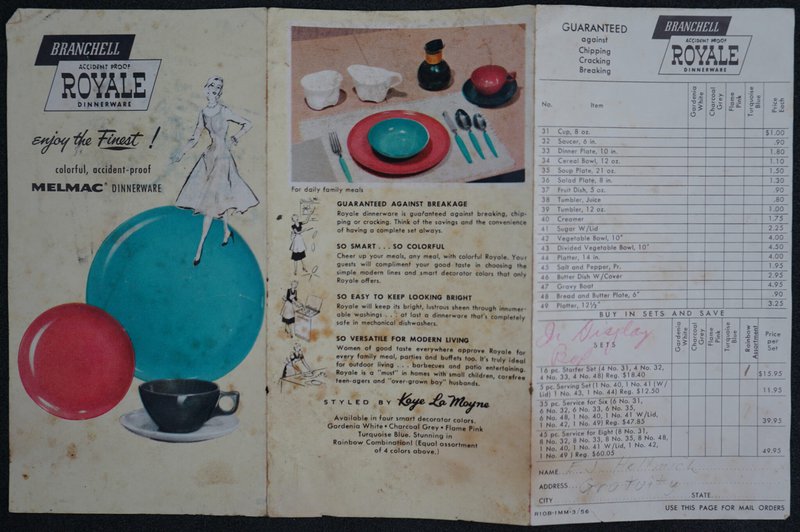

Melamine dishware, a thermoset plastic made of a laminate of melamine and formaldehyde, was lightweight, brightly colored, and durable—some lines even came with a Good Housekeeping certification that they wouldn’t crack, chip, or fade. The Branchell Company was among the early manufacturers of melamine dishes in the 1950s, a division of Hellmich Manufacturing Co. of St. Louis founded by Edward and Mildred (Mimi) Hellmich. Hellmich, a businessman, in large part owed his success to his wife Mimi, who, in the early 1940s, came up with the idea of plastic birthday candle holders for cake. With capital from this endeavor, they ventured into the quickly growing world of plastic housewares by way of Mimi’s next idea: high-style salad ware sets made of melamine. Ebonyte, the name of their first dish line, attracted the attention of American Cyanamid and their patented Melmac plastic; with investment by American Cyanamid, Branchell created the very popular Colorflyte and Royale series. So popular, that the St. Louis-based plant couldn’t keep up production with the demand.

Brochure for the Colorflyte line of patented Melmac (melamine) dishware. Edward Hellmich Papers.

Brochures for the Royale line of patented Melmac (melamine) dishware. Edward Hellmich Papers.

Brochure for the Royale line of patented Melmac (melamine) dishware. Edward Hellmich Papers.

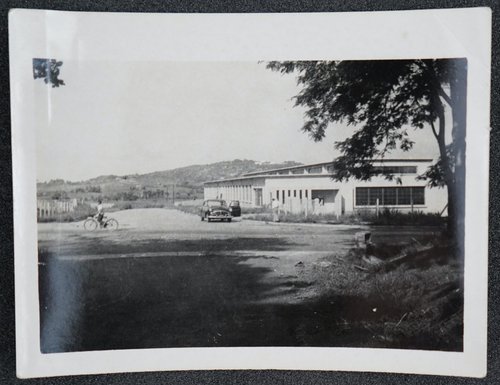

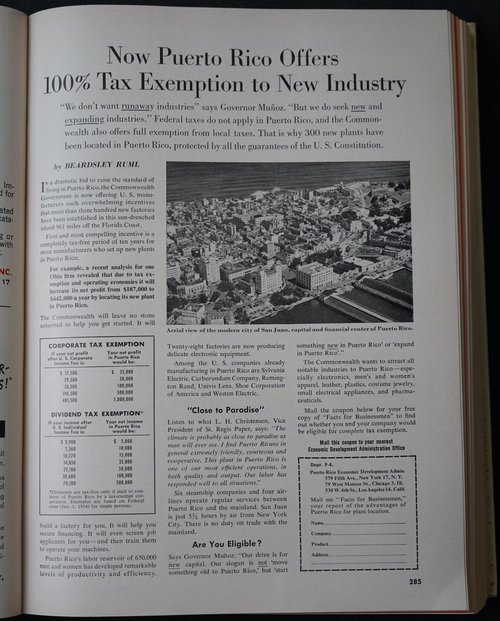

Branchell established a second factory in Bayamón, Puerto Rico. When I began researching Hellmich and Branchell in the Edward Hellmich Papers, I didn’t understand why there was such a distance between plant locations. While technically a part of the U.S. (though unincorporated1), the island is a far cry from the state of Missouri. But this was 1953, a time of focused efforts to attract mainland U.S. investments to the island nation. Beginning in 1947, Operation Bootstrap, or Manos a la Obra (“put your hands to work”), was the name given to a series of government programs meant to rapidly industrialize the agrarian economy through the attraction of industry investment. This took place largely through providing labor at costs below those on the mainland, access to contiguous U.S. markets without import duties, and profits that could transfer to the mainland free from corporate/federal taxation. Legal documents between Edward and business partners, lawyers, the treasury department, and banks within his papers suggests that he benefited from these incentives.

A view of the Branchell factory in Bayamón from outside. Edward Hellmich Papers.

Article from the Economic Development Administration Office. Modern Plastics Encyclopedia, Issue September 1956.

From Sugarcane to Petrochemicals

Puerto Rico’s economy was rooted in an agrarian society of independent farmers and sharecroppers before Spanish rule forced commercial cultivation of cocoa, tobacco, and coffee through enslaved labor. After the U.S. imposed control over the island, sugarcane plantations dominated by U.S. interests consumed much of the farmable land, forcing the import of food and resources to the island for the survival of the people. Half of the island’s population was always unemployed. This plantation colonial monoculture forced individuals to migrate to mainland U.S. in search of work.

The late 1940s brought the establishment of U.S. subsidiary plants into production through direct investment—importing the raw materials to the island and exporting the finished products to the mainland. Puerto Rico’s lower wage levels and the availability of its population of trained workers first attracted light manufacturing to the island (largely in textiles/garments). The manufacturing sector shifted from labor-intensive industries, such as the manufacturing of food, tobacco, leather, and apparel products, to more capital-intensive industries, such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, machinery, and electronics.

As lower wages and tax incentives ran out, foreign investment in the island left to seek ever-cheaper locations outside of the U.S. The island was pushed toward more intensive industrialization—petroleum and petrochemicals—big plants and machinery that could not easily be moved away from the island. Private enterprise failed to create “The showcase of the Americas”—an approximation of the mainland middle class that Operation Bootstrap foretold. Plastics was one of these fleeting investments in the commonwealth. Promises made by corporations for job security and a living wage never materialized. Half of the population depended on food stamps, and one out of three workers was unemployed.

Plenas of the People as Protest

The tradition of la plena is rooted in Puerto Rican and Afro-Caribbean cultures. The music encapsulates the struggles of the commoner in society amidst sociopolitical changes, operating as oral storytelling/history that otherwise wouldn’t be documented. Songs are often satirical, serving as means for the working class to gain empowerment through parody of their oppressors/oppressions. During this 20th century period, rapid industrialization became entangled with nationalist movements, and plena became the soundtrack to the fight for liberation. La plena cried for change—for the rights of workers, and for independence from colonial control.

Women operating the industrial machines and laboring to create handmade fine details on Branchell dishes couldn’t have been without the history of women’s hand skill in needlework and lace making in Puerto Rico in the earlier 19th and 20th centuries. While American capitalism opened the labor market to women, at the same time, it increased their exploitation as wage earners. Women became active in labor struggles—for a safe workplace, better wages, and the right to unionize. The Belfer Audio Archive is fortunate to hold a number of popularized plena recordings, a mix of joyful cultural expression and hardships suffered. “Alo…quien ñama?” was based on the events of the 1932-332 women needle workers strike in Mayagüez. In the song’s lyrics, seamstresses are calling each other on the telephone to raise mutual concern about the poor pay they’re getting in the factory for their garment handwork.

Audio snippet of a version of “Alo…quien ñama?”, performed by Ramón Rivera Alers. Bell Brothers Collection of Latin American and Caribbean Recordings.

The 45 of “Alo…quien ñama?.” Bell Brothers Collection of Latin American and Caribbean Recordings.

Here are the lyrics of the soundbite in Spanish, followed by an English translation (to the best of my ability as someone who doesn’t speak Spanish):

"Aló? ¿quién llama? [Hello? Who calls/Who is calling?]

¿Qué será? [What will be?]

¿Qué pasará [What will happen]

que el Taller de Mamey [now that the Mamey workshop (Mamey refers to industrialist William Mamery’s lace and handkerchief production)]

piden gente pa’ trabajá? [(they) ask for people to work?]"

From the documentation of an American company’s factory in Puerto Rico, a story of colonization, industrialization, incorporation, and dissolution is told. Contracts reveal ulterior motives, dishware brings to the surface the economy of women’s hands, folk music voices the struggles of the oppressed — all uncovering the creeping rootstalks of colonial control that self-seed and reap. I just told a story about plastics manufacturing in Puerto Rico, but it isn’t the story. I don’t know the names of the women captured in the photographs, what they felt throughout their workday, what the homes they returned to after quitting time looked like, who and what made their families and neighborhoods, or what skills and pains their bodies took from their work. Their stories remain untold.

Footnotes:

1 Puerto Rico is the Spanish name for the island, but the indigenous Taíno name is Borikén, and its people are Boricua. Spain colonized the island from 1493 until 1898, when the U.S. defeated the Spanish in the Spanish-American War, taking the island and forcing U.S. citizenship upon its inhabitants. Because it is still treated as an unincorporated territorial possession of the U.S., it is the world’s oldest colony.

2 One function of the National Recovery Act (NRA), a precursor to Operation Bootstrap, was to set industry standards for products, production methods, and wages. The codes developed for U.S. garment workers were applied to Puerto Rico in July 1933, and by August there were major strikes. Needlework was no longer considered skilled labor, or the work of artisans, but rather unskilled labor that could be paid hourly instead of by the intricacy of the pieces themselves.

The Edward Hellmich Papers (Edward Hellmich Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), the Socialist Labor Party Pamphlets (Socialist Labor Party Pamphlets, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries), and the Bell Brothers Collection of Latin American and Caribbean Recordings (Bell Brothers Collection of Latin American and Caribbean Recordings, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries) are part of SCRC’s manuscript collections.

Audio Preservation Engineer of the Belfer Audio Laboratory and Archive Jim Meade created the audio snippet of a version of “Alo…quien ñama?” and photographed the 45 of “Alo…quien ñama?” for this post.

Sources:

Ed. Acosta-Belén, Edna. Puerto Rican woman. Praeger, 1979.

Ed. Goggin, Maureen Daly and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Women and the material culture of needlework and textiles, 1750-1950. Ashgate, 2009.

Chase, Stuart. “Operation bootstrap” in Puerto Rico: report of progress, 1951. Prepared for the National Planning Association Business Committee on National Policy, 1951.

Modern Plastics Encyclopedia. Plastics Catalogue Corp., September 1956.

Rivera, Pedro and Susan Zeig. Manos a la Obra: The Story of Operation Bootstrap. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, City University of New York.

Rivera, Pedro and Susan Zeig. Plena canto y trabajo: Plena is Work, Plena is Song. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, City University of New York.